Vibrant and challenging complexities of decolonial thinking, intimacy, resistance, and joy are displayed in Venice, writes María Inés Plaza Lazo.

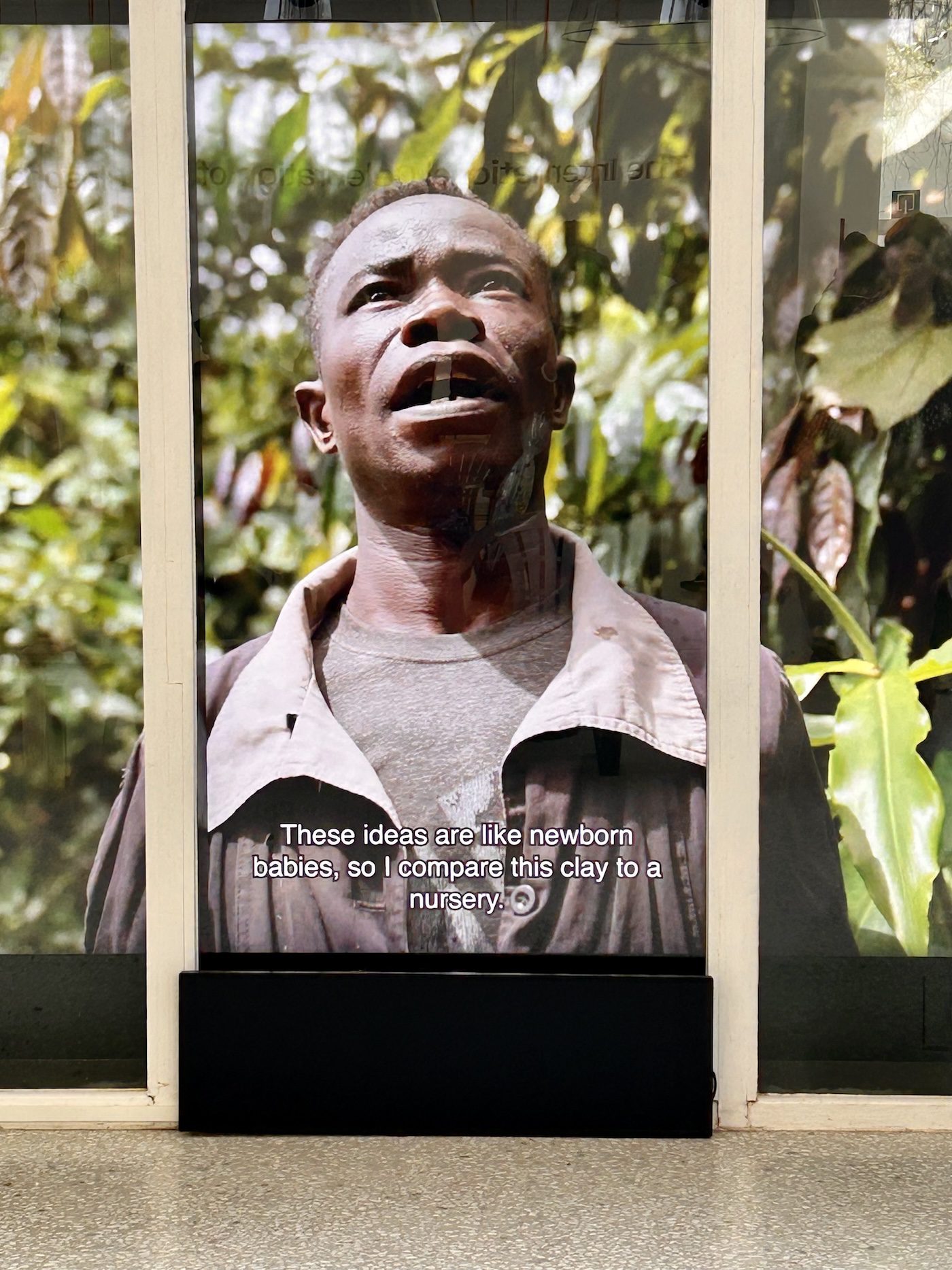

Karimah Ashadu, Installation view Venice Biennale Machine Boys, 2024. Photo: Lorenzo Palmieri.

Swallowed by one of the historical nuclei of Adriano Pedrosa’s Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, I found myself surrounded by ancestors. Portraits of people from all over the world gathered in what seemed to me an assembly of moments in life that were not held to be painted, but stitched into the fabric of daily existence.

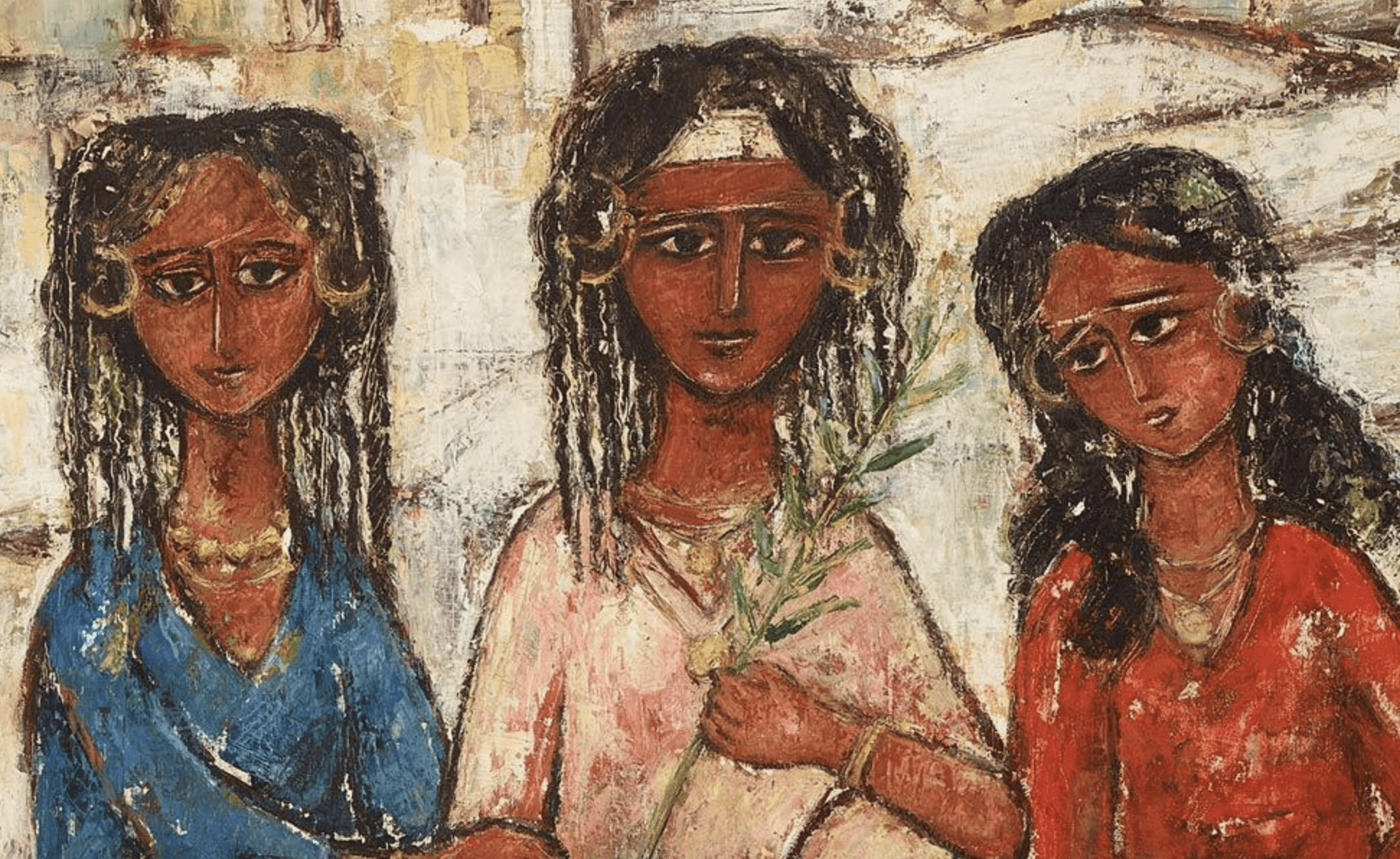

Apparently fortuitous, breathtakingly beautiful moments, such as: Two Old Ladies Shopping on a Cold Day by Gladys Mgudlandlu (1917/1928–79); Clinic by Mariam Abdel-Aleem (1930–2010), depicting a queue of patients waiting at the door to a medical station as a white dove soars above them; Three Nubians by Tahia Halim (1919–2003); Atelier by Chang Woosoung (1912–2005, Korean), in which he wears modern clothes next to a woman in white Korean traditional dress. Models for Cuban modernist Wilfredo Lam and Nigerian Uche Okeke looked at me, too. It seems that each artwork at this 60th edition of Venice’s International Art Exhibition is linked by the fact that it is being exhibited here for the first time, within gardens planted during an imperialist era and maintained by perpetually exclusivist and extractive structures. But isn’t that a bit reductionist for a curatorial frame? Or is this more than just “a debt being paid,” as Pedrosa said before the opening? Is what connects me intuitively to these portraits the fact that I myself am a foreigner, still, in Europe?

Tahia Halim, Three Nubians, 1975.

Foreigners Everywhere – Stranieri Ovunque is a strong title. It evokes a hope for antiracist labor and has borders abstract enough for each curatorial project to contribute its version to the main proposal, resulting in a display of vibrant complexities of decolonial thinking, in which struggles of the queer, the poor, the outsider, and the self-taught intersect. Yet even if there is no way around otherness in every room, the exhibition sidesteps crucial conversations about contentious issues such as migration, colonial legacies, and labor precarity within the art world – raising doubts about its inclusivity and political relevance.

This is no news to Adriano Pedrosa, who has publicly questioned the centrality of the Venice Biennale, insisting instead on the irreplaceability of “peripheral biennials” in his writings. Working within the contradiction, the Brazilian curator and director of the São Paulo Museum of Art has made an exhibition where presences outside the established canons of art production manifest what words cannot convey in our fragmented and polarized times. It is an antidote to prejudices about art’s lack of political relevance. The narrow focus of this curatorial pursuit is already a discomfort for many; “too museal,” “too simple,” “too flat,” “incoherent and incomplete,” I heard throughout the bridges and first reports. On the other hand, Foreigners Everywhere might be read as an invitation for the protests – such as ANGA (Art Not Genocide Alliance) –and poetic interventions on those bridges to be part of the constellations at La Laguna.

Within this dynamic, questions arise: what happens, beyond the act of displaying, between the artworks, and do connections fall into arbitrariness? Do identity politics add value, and thus come to be exchanged as forms of value not everyone is entitled to use? Who can really participate? And who is allowed to call for their ancestors? These questions remain open. With a museological gaze, Pedrosa himself, celebrated as the exhibition’s first Latin American curator, foregrounds a didactic explanation of foreignhood – from modernism, from society’s hegemonies, from art history, and consequently from the idea of nations – without challenging the structures that establish it. The tension is evident despite the subtlety with which everything in the main exhibition at the Giardini and Arsenale focuses on tools of liberation, in particular liberation from a Eurocentric perspective. It is this thread, issued from the so-called historical and contemporary nuclei, that achieves precious clarity between the main exhibition and some of the national pavilions and collateral events.

Yinka Shonibare, Installation view. Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo

At the Nigerian Pavilion, in response to curator Aindrea Emelife’s question “How do you imagine a nation?” artists from the West African Diaspora have created a “laboratory of imaginaries” that evokes the spirit of what late artist Uche Okeke called “natural synthesis”: an idea of nation born out of traditional love for art, burying the colonial past to understand belonging as unconscious, not forced. Not so much the batik-clad astronaut that Yinka Shonibare placed at the entrance of the Arsenale, bordering on the unnecessary kitsch of over-explanatory decoration; more the glass ball hanging from a steel structure that Precious Okoyomon built to receive transmissions from Nigerian diasporas and localities. Or the paintings at the Ethiopian Pavilion by Tesfaye Urgessa, who developed his visual language at Addis Ababa’s Academy of Fine Arts but also in Stuttgart and through his interest in painters like Lucien Freud. His references – spanning Ethiopian iconography, German expressionism, and Russian realism – have the capacity to channel all sorts of emotions around the relationship between art and nation that gain volume in Venice. For me, Urgessa’s exhibition at Palazzo Bollani turns into a reflective pole across the flood of identity-politics mania that this biennial propels in spite of its radical openness to the world.

Tesfaye Urgessa. Photo: C&

Especially at the national pavilions, this openness is fragile; it can be squeezed between the political interests of the supporting government and projections coming from all sides about what art should or should not do. This imminent exchange of values and agency is epitomized in the Benin Pavilion, curated by Azu Nwagbogu under the title Everything Precious is Fragile. Drawing inspiration from Yoruba Gẹlẹdẹ philosophy, in which female ancestors and deities as well as the elderly women hold a community’s power and spiritual capacity, the exhibition presents works by Hazoumè, Quenum, Akpo, and Bello that accentuate ecological concerns and the resurgence of Indigenous wisdom, beckoning viewers to contemplate our planet’s precarity by inhabiting an oil-tank construction. This art advocates for dialogue and introspection on pressing problems caused by an hegemonic economic order.

CATPC Installation view. Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo.

Which brings me to the Dutch Pavilion at the Giardini and The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred, by Congolese artist collective Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC) and brought together by artist Renzo Martens and curator Hicham Khalidi. The exhibition is one of many layers of the efforts of CATPC to reclaim depleted plantation lands and restore the Sacred Forest plundered by European colonizers. In Lusanga, the collective make sculptures from clay sourced from old-growth forests; they are then recast in cacao and palm oil in Amsterdam, as a fruit of their own labor but also as iconic representations of extractivist subjugation that the plantations in Congo still represent. Displayed alongside plantation-set films starring the artists, the sculptures embody a transition from painful past to the call for an ecological future. CATPC acts as an uncomfortable formation whose existence challenges the ideologies of dominance that have constructed the white cube as a clinical, segregationist space.

Installation view of South West Bank. Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo.

A celebration of Indigenous growing and gathering practices finds a place in the South West Bank exhibition, which emerges from the cultural and political work of further uncomfortable formations: Artists + Allies x Hebron (AAH), compelled by activist Issa Amro and artist Adam Broomberg, and Bethlehem’s Dar Jacir for Art and Research. Videos highlight participatory practices and community-driven workshops at Dar Jacir, contrasted with images from the ongoing AAH series Anchor in the Landscape, of burned olive trees in front of Israel’s separation wall. Among other artworks, Jumana Manna’s film Foragers explores the custom of foraging for wild edible plants and the resilience needed to do so due to Israel’s prohibitive “nature protection” laws.

Dana Awartani, Installation view. Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo.

Palestine is everywhere in this biennale. One example is Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s moving and disconcerting double-sided mural-sized oil painting Rage Is a Machine in Times of Senselessness – a layered composition in which machine-like structure elevates towards a lush landscape, emitting braids and plumes of red smoke, onto which Toranzo Jaeger has written “Viva Palestina Viva” several times. A banner shows cut watermelons, a symbol of Palestinian resistance but also an homage to Frida Kahlo’s final painting. Tableaus of nude women cavorting on a cloud are embroidered onto the canvas; on the back of the canvas the artist has scrawled Sappho’s verse “You burn me.” Another is Dana Awartani’s evocative installation of translucent silks medicinally dyed in warm colors and filled with patchworked stitches, soaked in kinship and the spirit of ancient communities. A requiem for heritage sites destroyed in the Arab region during wars and terror, the piece tenderly holds Palestine’s ongoing occupation and the devastation of Gaza through symbolic scars in the fabrics. Weaving, enmeshing, amalgamations, and non-linear narrations are the idiosyncratic fundamentals for an exhibition that prioritizes intimacy over conceptual coherence: every work infiltrates the others, every story seeks to be a co-dependent part of an international decolonial project.

Frieda Toranzo Jaeger (Detail). Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo.

The few works I can mention here from thousands of interventions, performances, concerts, lectures, essays, and installations contribute to the multifaceted narrative of the Biennale, inviting us to engage with the complex intersections of history, culture, and activism. And with joy. Here I must refer to Karimah Ashadu’s 8-minute film Machine Boys, honored with a Silver Lion, which explores the informal economy of motorcycle taxis in Lagos. Zooming in on the drivers’ bodies and their playful show off of masculinity, Ashadu highlights their vulnerability in a patriarchal culture. The video ends with one boy barking to the camera, theatrically, in rage. The socio-economic realities and gender dynamics of Machine Boys point toward the presence of a vehement discourse on neglected bodies, voices and discourses, even though opinions might tend to reduce it to randomness. Intertwining narratives of economic hardship and gender-related struggles, Foreigners Everywhere offers a plurality of identities, representations, and resistances, present as never before, visualizing the biases and intrications of the very act of curating in a space dominated by whiteness. No bigger narration seems to transcend borders and foster a sense of shared humanity in the tumult of our times.

María Inés Plaza Lazo is a founder and publisher of Arts of the Working Class, the multilingual street newspaper for art and society, wealth and poverty from Berlin.

More Editorial