The curator and researcher features three Moroccan artists in her current exhibition who challenge monotone perspectives of their country.

Contemporary And: The exhibition Quand je n’aurai plus de feuille, j’écrirai sur le blanc de l’œil (When I No Longer Have a Sheet of Paper, I Shall Write Upon the White of the Eye)—which is currently showing at the Villa du Parc art center, in collaboration with Le Cube – independent art room in Rabat—presents the works of artists M’Barek Bouhchichi, Abdessamad El Montassir, and Sara Ouhaddou.[1] How did you discover these artists’ practices?

Gabrielle Camuset: I came across the work of these three artists when I began working in Morocco in 2015. I got a sense of Sara Ouhaddou’s work at the Marrakech Biennale (2016) in the context of the exhibition Memory Games, which centered on the work of writer and filmmaker Ahmed Bouanani. She presented pieces of jewelry and faience, taking her own approach as a designer and blending it with the work of the artisan as a vessel and vehicle of knowledge. After that, she established her studio in Rabat, and our paths crossed regularly.

Around the same time, M’Barek Bouhchichi showed his Black Hands work at Kulte Gallery in Rabat. The show was suggestive of craftwork, which the artist combined with the history of Morocco’s Black populations, posing questions about our roots and the current situation in the country.

I discovered the work of Abdessamad El Montassir when he took part in Le Cube’s summer lab residency in Rabat.

Over time, I noticed that their practices created linkages between issues that I think are interconnected in the realm of contemporary art.

C&: These three artists, whom you have brought together at Villa du Parc, each construct a memory of orality in their own way. How did the exhibition come into being from a curatorial point of view?

GC: The exhibitions I have put on at Le Cube center on specific issues: narrative reification, the need to step outside of monolithic discourses, and the possibility of accepting upheaval. I think the approaches adopted by these three artists enter into a reciprocal relationship with these issues in ways that are both complementary and singular. What interests me about orality is that it includes the idea of hypothesis and lapses in memory. This constitutes a way of thinking about our world that gets lost in many contexts—in Morocco and elsewhere—while this acceptance of something missing opens up a multitude of possibilities.

The exhibition has an affinity with this: the works that are presented set up hypothesis , modes of decentering that are able to escape from a generalizing viewpoint.

I also wanted to move away from Morocco’s big metropolitan centers, like Marrakech, Casablanca, Rabat, Agadir, and Fez, and focus on other geographical locations. This exhibition makes sense in Morocco and France—and in many other contexts.

C&: How would you describe the selections made for the exhibition? Outside of orality, one of the other key themes that struck me in this exhibition is that it is based on artistic propositions with their roots in collaborative approaches that seek to find a legitimate form for orality.

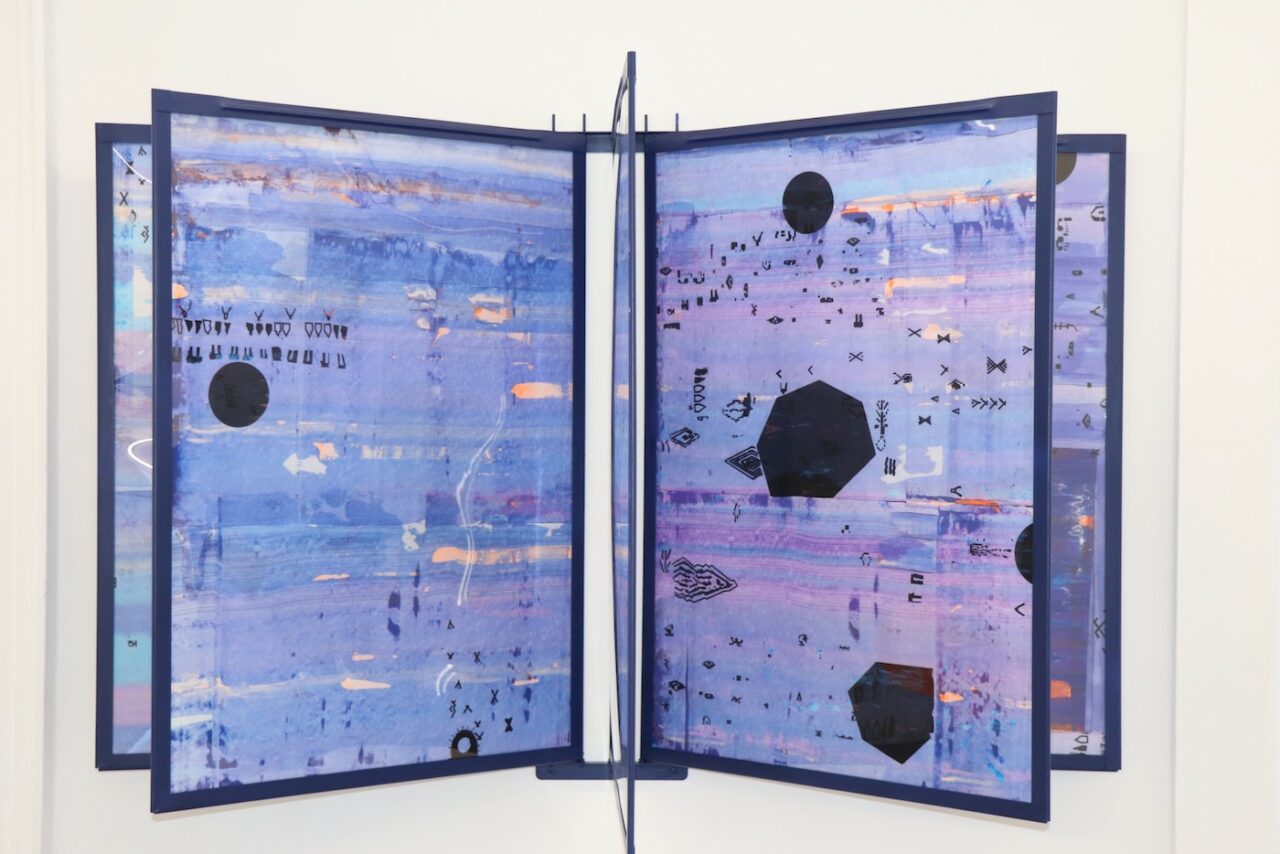

GC: Sara Ouhaddou began working with Moroccan embroiderers in 2013 and still collaborates with one of them today. The women finished this long-term collaborative work, which has both a plastic and a technical dimension, with the large “untitled” embroidery from the project Des Autres (2021), which was shown at Villa du Parc.

They reflected together on the embroidery’s motifs and the techniques used in making it, looking for the meanings contained in it. The motifs represent an interpretation of the different cycles in a woman’s life: maid, bride, mother, widow … In returning to the stories, tales, and myths, they realized that a figure that had for a long time been identified as the bride was actually potentially a goddess. Ouhaddou is an artist who collaborates with different artisans (working with textiles or glass) in an attempt to formulate works as hypotheses, through the telling of different stories that come out of an ongoing process based on encounter and exchange.

She presents her research at Villa du Parc in a space resembling a drawing board. The design that is displayed on the cartography she sketches here after the fact is deliberately incomplete. It is a space of research and enquiry that takes a free approach to relating different nexuses to one another.

Abdessamad El Montassir follows a somewhat parallel approach. Since 2013, he has been working together with poets from the Sahara, the region he is from—including one particular childhood friend of his. Everything that is produced is discussed collectively and the issues, particularly in terms of the way this poetic material is used, are tackled in the research process. His work Al Amakine(2016–2020), for example, comprises a photographic installation involving light boxes and a sound piece. It takes as its starting material poems in Hassānīya—an Arab dialect spoken in the Sahara in southern Morocco and Mauritania. Not wanting to simply play recorded poems, El Montassir instead used this material to create a new piece in collaboration with composer Matthieu Guillin. As a reference to the impossible diction, they decided to work on the breath, the breathing, and the silences, offering up a unique sound composition. They also worked on capturing plants—non-human elements are very important in Sahrawi culture. A similar methodology is at work in the film Galb’Echaouf (2021), which is the fruit of a long-term collaboration with its protagonists, some of whom have worked with El Montassir on all his projects.

C&: M’barek Bouhchichi’s work Muqarnas (2022) made a real impression on me because of its sensitive experimentation at the level of material and form.

GC: The work is composed of four muqarnas, an architectural motif that can be found in many Muslim countries. Each muqarnas is based on a yoke, in a kind of puzzle comprising several different elements.

The artist found one of the original painted wooden muqarnas in the exhibition in a second-hand market in Morocco and presented it as was. A second muqarnas is also original and is likewise made of painted wood. It was restored by Bouhchichi using traditional colors. The third is another variation of the same thing, comprising unpigmented wooden elements. Finally, the fourth muqarnas is made from resinous components. This work is a form of reinterpreted learning, a legacy of the techniques that the artist has carried and transformed. It shows that there is a complexity beyond appearances that is woven into several layers. Adjacent to this work, he presents a selection of pages from his work notebook, including sketches and research recounting his travels and the people he met along the way. These pages immerse us in the artist’s working procedures and thought processes.

C&: Were you trying to create or recreate a spatial experience for someone going round the exhibition that would be like walking through a landscape and channeling multiple narratives, archives, and images?

GC: My hope is that visitors to the exhibition, whatever their situation and background, will learn something new and find out about some little-known aspects of Morocco, without it becoming didactic. M’Barek Bouhchichi comes from Akka, Abdessamad El Montassir is from Boujdour, and Sara Ouhaddou is French with Moroccan origins and comes from a family of artisans. All three look to interpret the country and its cultures differently. For example, I wanted visitors to stroll through El Montassir’s installation Al Amakine and become active observers. The poetry that serves as the basis for his project tells of events that are taking place, which may be political, cultural, or social; poetry is still being written today and it also enables movement within the territory. The places in the photographs are connected by the poetry, by spatial and temporal markers of distance. The installation deploys a kind of fictional cartography here.

The exhibition is not just a landscape, its scenography is intuitive—each work exists in its own space while being inscribed in a larger narrative.

C&: The exhibition opens up to this idea of a living archive that is both transparent and accessible. In the parallel exhibition CASABLANCAS (curated by Maud Houssais), it is evident that from the period of modernism in art through to the present, standardization has been consistently rejected in Morocco.[2] To what extent does decentering these practices allow us to do work in this vein?

GC: In the exhibition Quand je n’aurai plus de feuille, j’écrirai sur le blanc de l’œil, M’Barek Bouhchichi, Abdessamad El Montassir, and Sara Ouhaddou put forward a complex interpretation of a certain rejection of standardization. Our image of a country is often rather monotone: the middle class is defined in a particular way, the religion is Islam, the only language is Arabic, people have the same skin color, and there is a single general culture that is shared and has persisted. Morocco’s future will be built on the basis of a serious consideration of the place occupied by Black Moroccans in society and of how people from sub-Saharan regions fit into its communities. Thought also needs to be given to the Amazigh’s position in all areas of the country, as well as to the perception and understanding of Saharan knowledge and cultures in southern Morocco, beyond all the tensions the region is beset with.

Art makes it possible to give a place and a voice to people whom we are completely ignorant of.

The exhibition runs from January 22 to May 7, 2022 at Villa du Parc, in collaboration with Le Cube – independent art room.

Gabrielle Camuset (b. 1987) is a researcher and curator. The main focus of her research is on issues relating to postcolonial theories in our contemporary contexts, particularly in Western Europe and North Africa. She tackles these issues using an intersectional approach, while taking care to link up the specificities of each practice and context.

Karima Boudou (b. 1987) is an art historian and curator and has a position as a research assistant at the Bern University of the Arts (HKB). She lives and works in Brussels. Engaging at both a theoretical and practical level and operating at the interface between postcolonial theory and the reactualization of the archives and decentered histories of modern and contemporary art, her work involves a strategic consideration of the politics of vision and visibility in art history.

[1] Launched in Rabat in 2005 by Elisabeth Piskernik, Le Cube – independent art room is an exhibition, residency, and research space dedicated to contemporary artistic practices.

[2] Curated by Maud Houssais, CASABLANCAS is an exhibition of archival material presented in the Villa du Parc’s Veranda space. It refers to the intellectual and artistic shift that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s at the École des beaux-arts, Casablanca’s school of fine arts.

More Editorial