Enos Nyamor looks back at a year in the arts marked by collective mourning as a cosmic bond between Africa and the diaspora.

The 2010s bowed out of the stage with unceremonious commotion. An anti-racist uprising in the West, a pandemic without an end, increasing awareness of the politics of essential work, and an influx of quarantine-inspired art projects. And the entrance of the 2020s has been no less rambunctious. Fiery grief – the kind that set hearts pounding, feet shuffling, bodies trooping, streets flooded, smoke billowing, and statues toppling – has framed some of the most outstanding large-scale exhibitions over the past year.

Okwui Enwezor’s legacy lingers, and one manifestation of this, in New York, was an intergenerational survey of mourning as a recurrent motif in artistic expression in the United States. The imposing high walls of the New Museum enveloped objects by thirty-seven artists. Grief and Grievance: Mourning and Art in America was an important exhibition. In highlighting the perennial abuses of the justice system through sustained violence, it enacted immediate distress. For me, no other show was as timely or articulate in its precise representation of facets of grief, creating a shared conceptual map for reorientation of Black consciousness.

In Arthur Jafa’s landmark video Love Is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), sounds from the video of ornate funerary rights in rural Southeastern Nigeria wafted toward a boisterously mellow chorus – an extract of Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam.” Not only was the exhibition’s exploration of grief territorial, reflecting on the isolated Black experience in the United States, but also put forward to collective mourning as a cosmic bond between Africa and the Diaspora. The American Civil War aroused unending grievances, particularly in the southern states. But the grief we, as dedicated visitors, could glean from that allusion to the Middle Passage, and the reality of separation, is the longing that, in absence of mourning, transforms into intergenerational rage.

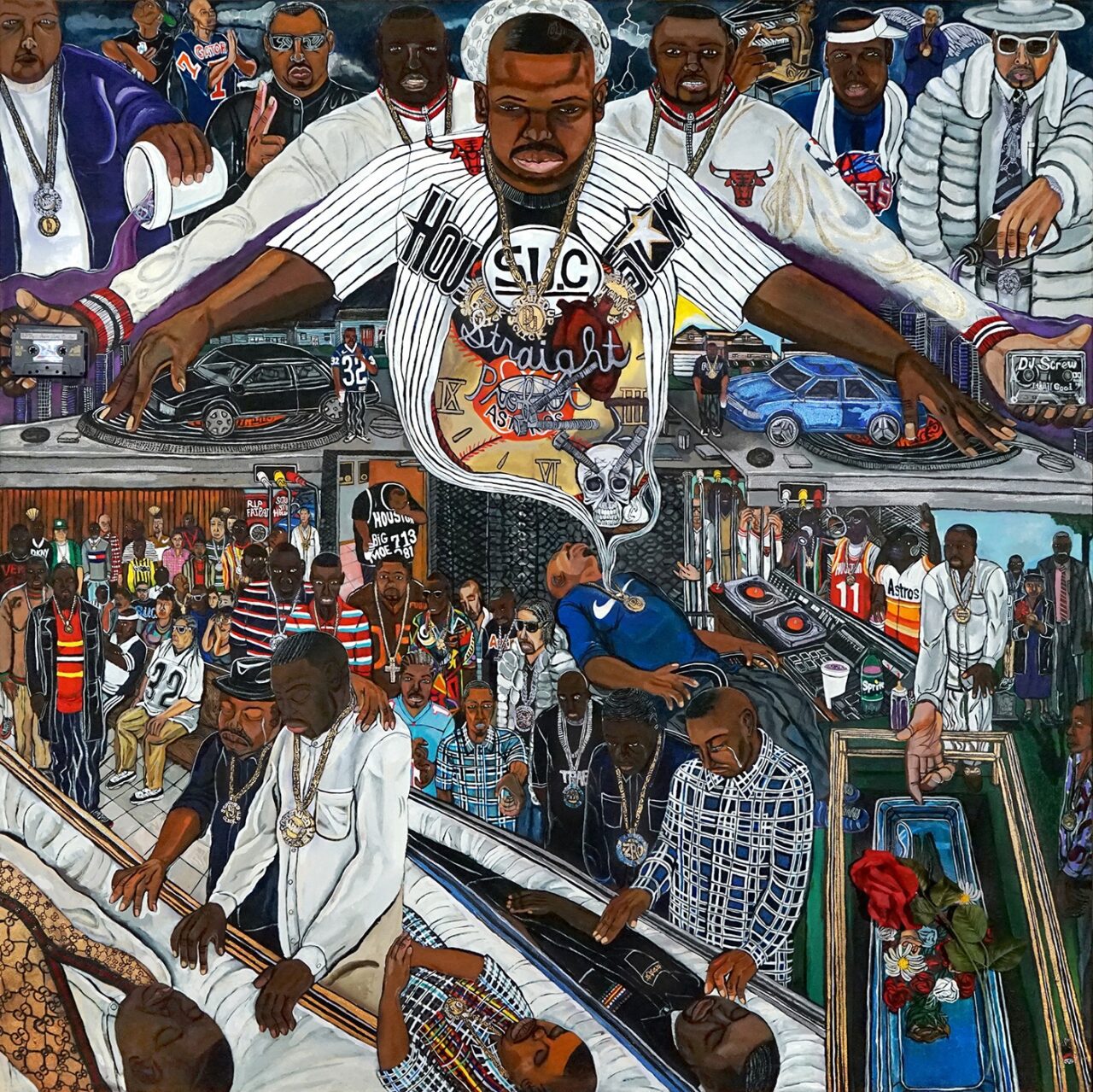

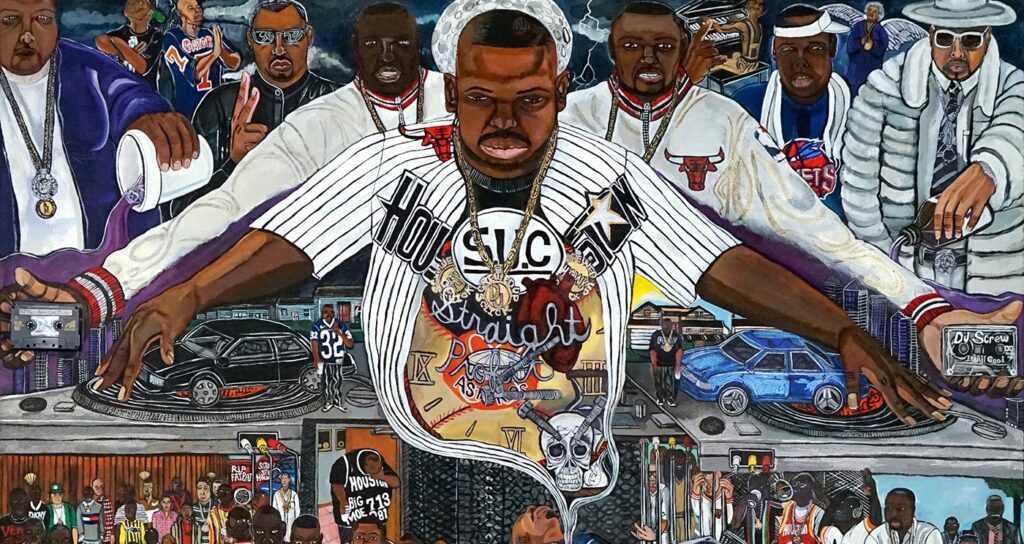

Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and Sonic Impulse, at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, highlighted the complex nature of Black nationalism, and the diversity of Black cultural experience in the Southern states. Because the South is the home of jazz, the exhibition meticulously unraveled the interface of music and voice as primary elements of Black experience. Once again, grief was a prominent link. A centerpiece in Dirty South was El Franco Lee II’s painting DJ Screw in Heaven 2, 2016. In this piece, populated with geometrically distorted figures, celebrated late American DJ Robert Earl Davis is depicted both in a casket and with both hands stretched out in the gesture of tuning a deck, as tears flow down his face.

I found Paul Stephen Benjamin’s Summer Breeze (2008), a video installation of twenty-eight cathode ray tube screens, to be indubitably the most urgently compelling item at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Billie Holiday’s 1959 rendition of “Strange Fruit,” a song that lamented the mob justice and lynching prevalent in the segregated US, serenaded visitors as the combined intense blue light from the multiple screens refracted, and the virtual space created by the medium was laced with the lyrics “Black bodies swing in the sun” streaming from the monitors.

In the past year more figurative paintings, miracles of seduction, have revisited the convergence of Black bodies, in a crystallization of an “Afro-politan configuration” tendency. There has been such flavor in color, such prominence in features, in representations of the Black body – Blackness as a luminous texture on both screen and canvas. Beckoning from the soundless expanses of Sungi Mlengeya’s panitings and Stacy Gillian Abe’s work is a visceral vibration emanating from bodies in spiritual dimensions.

In Mlengeya’s Precontemplation (2021), included in the exhibition Just Disruptions at Afriart Gallery in Kampala, an expansive white background wraps the figure. Dangling bodily organs charged with a vital energy cast the impression of a two-dimensional relief soaked with light. Because of the washy strokes, the dark, conspicuous surfaces representing Black femininity emit a glint. This glow is also present in Stacy Gillian Abe’s painting R is for Rosie (2021), in which a half-clothed figure, shrouded in a purplish hue, reclines on a bed – somehow suggesting an untranslatable spiritual immanence.

In the exhibition Longing, on view at Mariane Ibrahim in Chicago, the Nigeria-born artist Peter Uka takes up Zadie Smith’s idea of “absence of historical nostalgia” as the totality of African Diasporic encounters. The fashion and background designs in his paintings are residues of past cultural elements, and are supposed to convey a vital nostalgia. Uka’s vivid expression is especially visible in Blue Jacket (2021), where a figure whose gleaming, luminescent features are saturated with light and glowing. In spite of the charm of the glint, such imagery is inseparable from tragedies and discarded memories.

Greater New York, a large-scale exhibition at MoMA PS1, also flashed bright, demonstrating a striking awareness of the intimate interconnection among creatives and collectives in Greater New York region, particularly as Diaspora in a land whose native ownership is contested. For me the condensed time suggested by the heavy presence of video installations was positively edifying. Emphasis on time-based media can be a strategy of diversion from the attention deficit of the connected world. In addition to its interest in temporal depth, in Diasporic encounters, and in the textures of gender disidentification, grief loomed over this visual survey too. In Cenotaph Won’t Hold (2021) and A Sartorial Monument(2021), Lachell Workman deploys an intuitive sense for material, especially in connection to specific emotionally disruptive events. Funerary t-shirts with commemorative messages dominate Workman’s oeuvre, emblematic of collective mourning rituals that have gained prominence in the continent of late.

Punctuating the Greater New York survey was “(Never) As I Was,” a showcase of new works from Studio Museum in Harlem’s Artist-in-Residence program. Jacolby Satterwhite’s Shrines (2020) offered a video installation containing layers of immersive experiences and screenshots. Widline Cadet’s nourishing photographic work mulls over intergenerational connections and disconnections in Caribbean Diasporic experience. In Pou Lè Demen Kòmanse San Nou #1 and Pou Lè Demen Kòmanse San Nou #2 (both 2021), Cadet embeds two videos on photo prints. Placed on opposite walls, the videos were in coded to play concurrently, the duration before each playback marked in distressing spurts of silence. Texas Isaias’ multimedia work channeled a space for spiritual orientation and mourning. Their photograph New World in My View (2021) portrays a non-binary subject in ritualized states of self-care implied by proximity to nature, but also presupposes the inevitability of estrangement in the disidentification process.

Perhaps all these hints, as images, sounds, and installations, are reminders that it is time to activate radical mourning strategies to reject a cycle of rage that ignites grievances and counter grievances. To emphatically insert feelings, in resistance and subversion, as reimaginations of a kinder loving world. And though grief is a universal human condition, perennial loss is a shared legacy between Africa and the Diaspora, a connection forged by centuries of abduction, enslavement, colonialism, and now neocolonialism and economic migration. In Brazil and Lusophone Africa, this palpable grief, mired in restless despair and repressed anguish, is be described as saudade. It is a subterranean grief that transplants itself as strands of memories, shared as stories across generations, of a loved one who left for a walk, or went to the stream with a pot or to fish, and never returned.

Enos Nyamor is a writer and journalist from Nairobi, Kenya. He works as an independent cultural journalist, and because of his background in information systems and technology, which he studied at the United States International University, he has gained interest in new and digital media.

More Editorial