Fatimah Tuggar’s work is included in the exhibition Beyond what we see at Les Abbatoirs in Toulouse for Africa 2020. In a conversation with Enos Nyamor, she talks about casting a clear-eyed look at art, technology, and their relation to one another and to the societal issues of our time.

Contemporary And: New media has been your primary mode of expression for more than twenty-five years now. What induced your initial engagement with the digital as an expressive platform?

Fatimah Tuggar: I am not sure that “new media” or computer-generated imagery has been my primary mode of expression – it may be the most published or popular aspect of my work because of people’s affinity for the computer. It is undoubtedly the most translatable for screen-viewing. My approach is to choose and use the medium that best serves my ideas. Whether using a computer or a hammer, the most useful medium depends on the context. My work focuses on technologies and their cultural impacts, from hay brooms to radio signals to algorithms.

C&: Do you consider digital media as a tool or as an extension of human senses?

FT: Yes, I see digital media as a tool and maybe as an extension of humanity in the sense that it reflects ourselves to us. It can serve humanity, or it can mirror the worst aspects of society. For example, Ghana and Nigeria have both started using mobile telemedicine to track rural shortages of doctors, blood, and medication. But when we use digital technology for surveillance capitalism or predictive policing, it is a different story. Or, to continue the hammer analogy, one can use a hammer to build or to break down things. Tools don’t have consciousness unless we are talking about the potential of AI in the future. For now, it is learning from us and thus revealing the biases of its coders.

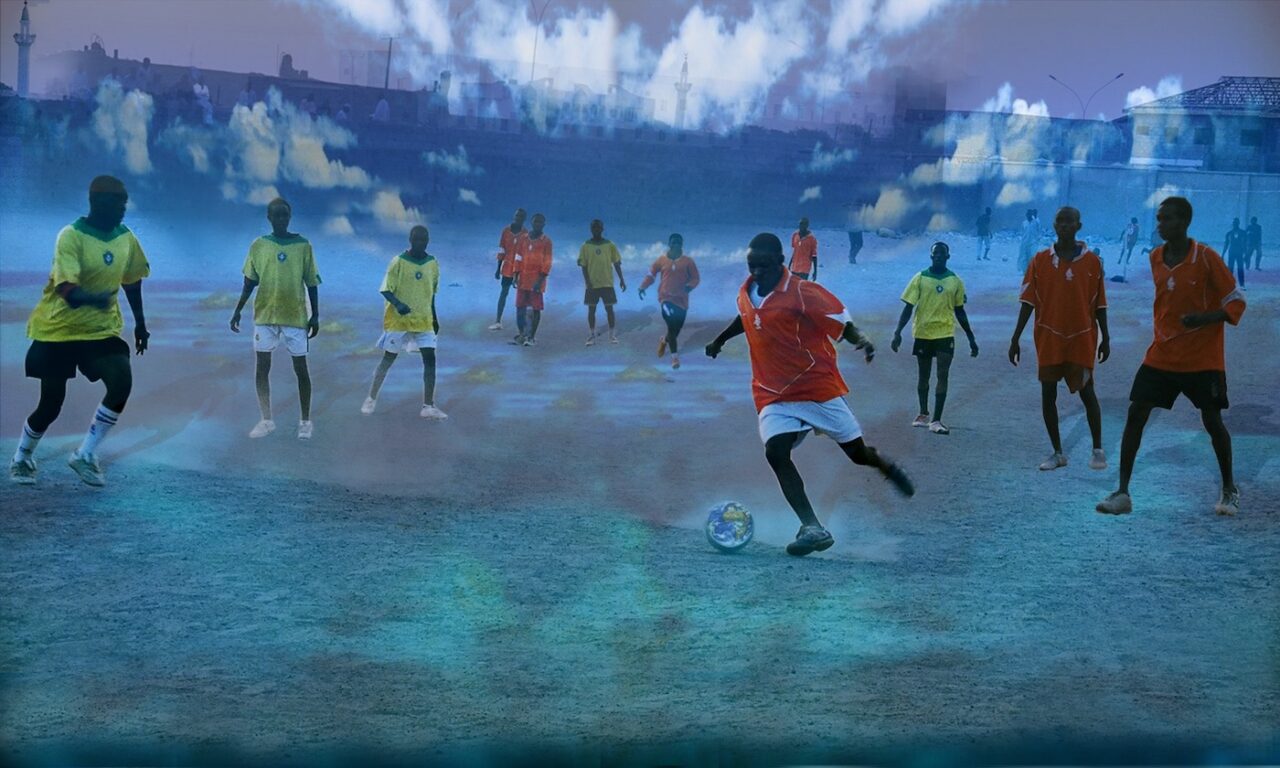

C&: Dreaming was a connecting thread for your retrospective at the GreenHill Center for North Carolina Art in 2011. In one of the works, Dream Team, you deconstructed and added to a photograph of football players. Does this suggest that new media can infiltrate and enhance the unconscious landscape of dreams?

FT: Dream Team and other football images were produced based on an invitation from FIFA for the World Cup in Johannesburg in 2010. While we could not reach an agreement for using the montages, I had always wanted to produce work about “the beautiful game.” I had great experiences playing as the only girl in my neighborhood. I understand the love of sports and its connection to hopes and aspirations for players and fans. The technological focus in this image relates more to how, despite the fact that many Africans don’t have the same access to the same technology behind diets and sportswear, they can sometimes rise to the top of the game based on pure heart. In terms of the landscape, sky images and underwater images brought together places humans cannot inhabit, in the same way that we often have to reach beyond our grasp to succeed. The work is a celebration of Black men and positively relating to them.

C&: In Lives, Lies and Learning (2019), with a Marxist concern for the exploited workers within academia, you intended to critique fantasy, rather than generate one. Were you concerned about fantasy, as generated through new media, as a solution in itself, and which can generate situations that are perhaps unconceivable without the new media?

FT: I think you misunderstood my comments in that interview. Lives, Lies and Learning is a commissioned artwork based on a collection of experiences of different people I have encountered in academia over the last fourteen years. I created the artwork by writing short dramatic monologues, which I had actors act out, and then I made animations from the recorded live footage. The animations are turned into holograms as a metaphor for how hollow the promises of freedom of inquiring and access to education can often become.

What I said about fantasy is that science fiction looks with nostalgia to the past or makes future predictions. I work with what I call an “alternative imaginary” – the work is anchored in the present. The focus is on imagining what is possible with the resources we currently have. I have also used fantasy to create moments of relief from the harsh truths of the present or historical in AR or VR works. Sometimes that strategy involves bringing humor, play, or change in scale to have experiences that would otherwise be impossible.

C&: You have spoken of a demand for your digital objects to be African, or the misconception that they are not African enough. Is it possible that the “African-ness” in your work consists of reinventing sacred objects, reimagining customs, and thus inserting certain ontologies within technologies of expression?

FT: As I wrote in the 2018 article in African Arts, “Methods, Making, and West African Influences in the Work of Fatimah Tuggar,” I am not interested in conceding digital technology or any other kind of technology as being only for Western Europeans. I see myself as a stakeholder in computing – especially because long before fractal mathematics was used for the computer, it was used in many West African communities as a system for town planning, architecture, governance, and aesthetics. Furthermore, the coltan used for electronics often originates from the African continent – Congo, Mozambique, and Ethiopia. Like oil, it comes at a high cost to local communities. Besides, we are all building on prior knowledge.

Customs are dynamic and evolving, regardless of any deliberate efforts on our part. I am not focused on “reimagining” or “inserting ontologies.” I do not operate from a place of reactiveness. I remain curious about understanding the impact of technologies and the power dynamics underlying them.

C&: Technologies have also contributed hugely to various forms of imperialism and cultural obliteration, leading to a widespread positivism. But studies also indicate that technologies enabled resistance through magical experience. Is there room for mystics within contemporary technologies of expression?

FT: Yes, let’s hope there is room for all kinds of pursuits and practices as long as no harm is done. That is why freedom of inquiry is so important. For me, magic and mysticism have a side that suggests qualities of superiority and power over others. Mine is not a pursuit for the magical or mystical. Mine is a pursuit for understanding the application of knowledge for practical purposes grounded in daily life.

C&: Digital technology has the potential to virtually eliminate space, blurring distance between the local and global. How can local agencies resist disruption and overcome extinction while under this unbearable force of digital universalism?

FT: I am not sure that I share your perspective of “digital universalism” or, as it used to be called after Marshall McLuhan, the “global village.” Many on the planet, in the sub-Saharan region and many other regions, are still without stable electricity, running water, and other necessities. While it is true that many own mobile phones, only the elites have computers in Africa – about 7.7% of households in 2019. The most pressing digital issue is algorithmic education. Across the globe, there is a lack of understanding of how what you are calling the “virtual elimination of space” works. The freeness of social media comes at the cost of our building an ongoing, pervasive unconscious habit to share one’s information so that it can be swept up and used for advertising, surveillance, and the perpetuation of polarization through lies and disinformation. This has become the norm.

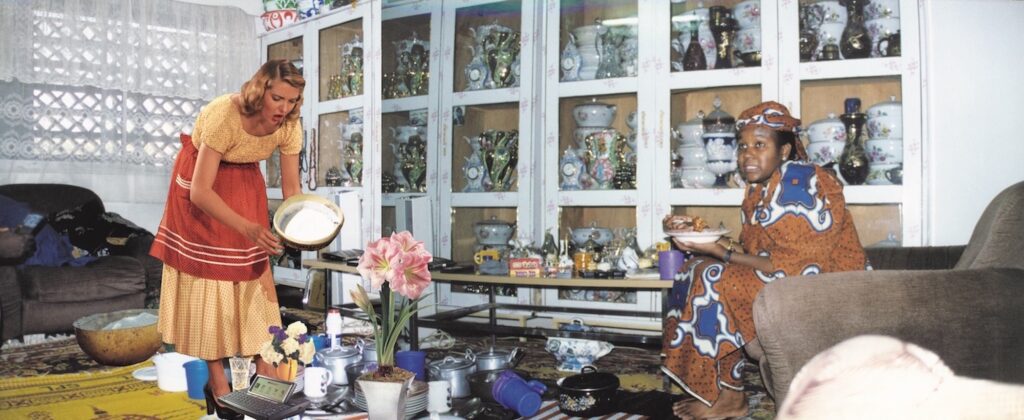

C&: You have explored gender and technology as an extension of discussions on the social implications of technology. For example, in Fusion Cuisine (2000) you juxtapose rural Nigerian everyday life with that faced by women in the West, where technology has supposedly liberated them from domestic chores. Still, in what ways can new media liberate us from restrictions imposed by imperialist, patriarchal systems?

FT: As I mentioned, I do not think technology can magically change human shortcomings or biases. We have to actively and consciously work towards equity in life and digital systems through education, policy, and coding. As an artist, I think my role is to creatively and imaginatively question, make things transparent, and, when necessary, be a culture jammer and resistor. The way forward is for everyone to insist on social equity and environmental justice using whatever skills and resources they have. Change usually comes from an integrative approach.

C&: Do you consider emerging digital art trends, such as non-fungible tokens, as offering a route of access to these practices?

FT: Let’s hope, eventually. There is a path forward for meaningful works within “emerging digital art.” Now it is in its infancy, sort of the way people used to scan their paintings in the early to mid-1990s and call it digital art. The quality of the work and its content has to improve, and that will happen with time. I see a level of self-consciousness about being trendy and focused on its digitalness that doesn’t serve the work. For me, the best way to make art is to stop thinking about making art or limiting oneself by media or by naming conventions. I focus not on whether I am doing art but on communicating to people regardless of their visual and technological literacy. The goal when making art is to avoid applying technological answers to aesthetic questions. This approach requires an understanding of the technology, its utility, and resisting whatever charm or status it is supposed to signify.

Fatimah Tuggar is an interdisciplinary artist living and working in the US. She is currently an Associate Professor of AI in the Arts: Art and Global Equity at the University of Florida.

Enos Nyamor is a writer and journalist from Nairobi, Kenya. He works as an independent cultural journalist, and because of his background in information systems and technology, which he studied at the United States International University, he has gained interest in new and digital media.

More Editorial