Notre auteure Elisa Pierandrei s’est entretenue avec l’artiste algérien Massinissa Selmani à propos de ses dessins énigmatiques et ambigus.

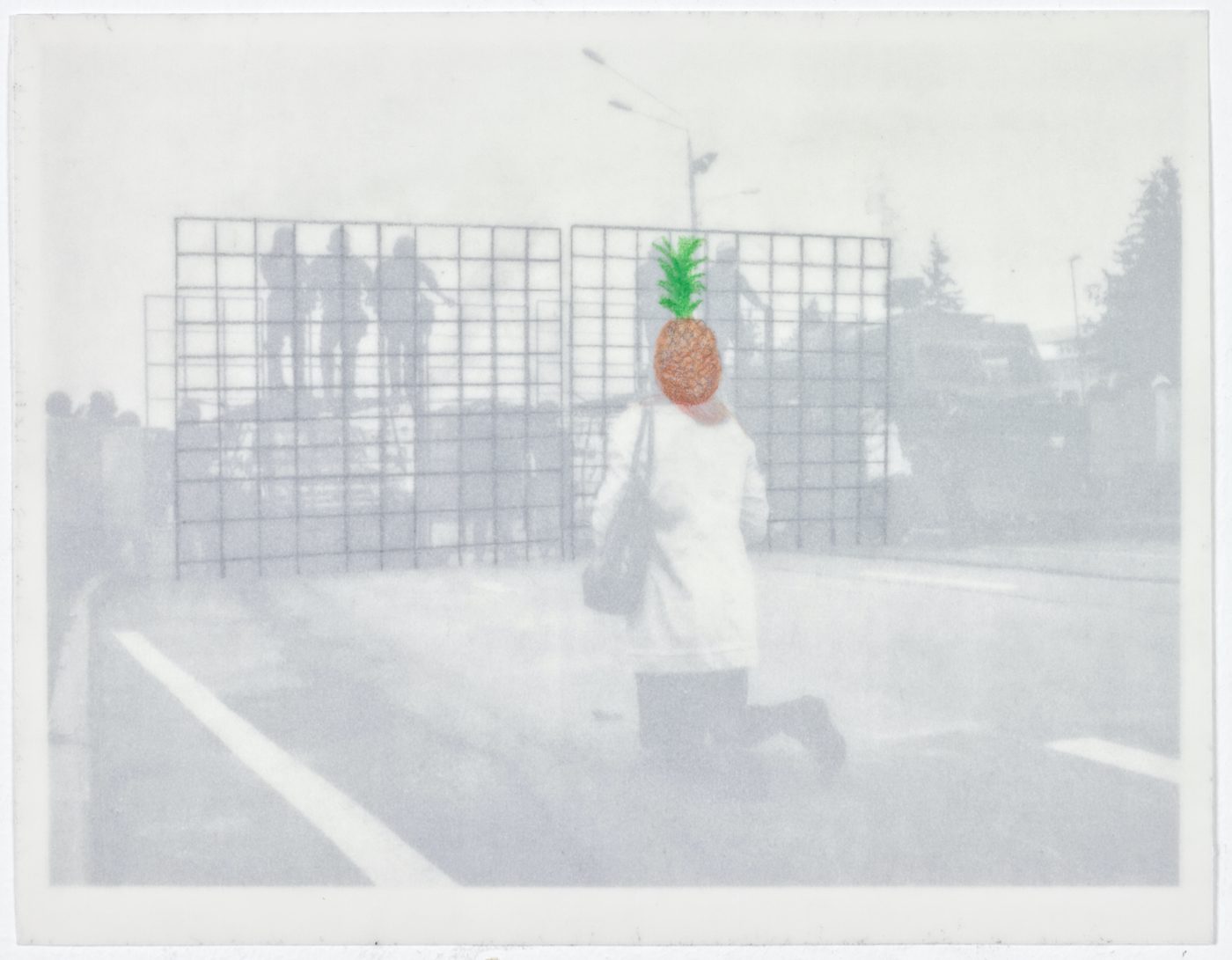

Massinissa Selmani, Untitled # 7, 2021 (Alterables series). Photocopy, graphite and coloured pencil on paper and tracing paper, 15,5 x 19,8 cm. © ADAGP Paris - Courtesy Galerie Anne-Sarah Bénichou, Paris

Contemporary And : Votre pratique artistique allie dessins et animations en boucle qui révèlent des scènes énigmatiques et ambiguës.

Massinissa Selmani : Mes animations en boucle mettent en scène un mélange de comédie et de tragédie, des narrations rattachées à l’environnement dans lequel j’ai grandi. Les travaux que j’ai réalisés jusqu’ici ont une durée de quelques secondes. Ils sont comiques ou absurdes et font rire la première fois qu’on les regarde. Mais c’est la répétition mécanique de ces blocs qui transforme l’action en tragédie. Par exemple, j’ai réalisé une animation montrant un homme qui essaie d’insérer son bulletin de vote dans l’urne. Un homme se trouvant à ses côtés applaudit. C’est hilarant d’observer son échec renouvelé. Imaginons à présent cette scène vue en boucle dans une exposition, toute la journée. Ces animations courtes, dont je dessine chaque image à la main, sont aussi une manière d’explorer l’acte de dessiner et ses différents langages.

Prétextes, 2019, looped animation, no sound. © ADAGP Paris. Courtesy Selma Feriani Gallery (Tunis-London) and Galerie Anne-Sarah Bénichou, Paris

C& : Inspirés par des événements récents, certains de vos travaux sur papier, obsédants mais directs, prennent une teneur plus politique. Pouvez-vous nous livrer plus de détails sur les sources traditionnelles dans lesquelles vous puisez votre inspiration ?

MS : Je considère mes dessins comme des formes documentaires mêlées à des constructions fictionnelles ; mes œuvres s’apparentent davantage à un engagement distant qu’à un militantisme féroce. L’histoire algérienne a inspiré certaines de mes œuvres, telles que 1000 Villages en 2015, lorsque je me suis penché sur les expériences de l’agriculture socialiste entreprises par le gouvernement algérien en 1973. Les sujets socio-politiques m’intéressent aussi, telle que la représentation de la violence et sa perception à travers les médias : écriteaux, objets, postures, gestes, décisions, mots, contes, situations absurdes ou impossibles qui parlent de violence. Je n’ai jamais été confronté à la violence extrême au cours de ma vie, mais j’ai vécu mon adolescence en Algérie pendant la guerre civile. Et cela a eu des répercussions sur moi. Comme pour de nombreux ressortissants de ma génération, le sentiment d’être menacé est toujours présent.

Massinissa Selmani, 1000 villages, Drawing 2/20, 2015. Drawings on double pages and notebook cover. Graphite, marker and transfer on paper and tracing paper. Collection Frac entre Val de Loire, France. Courtesy the artist.

C& : Comment construisez-vous vos œuvres ?

MS : En réalité, nombre de mes œuvres sont dérivées d’images photographiques fragmentées trouvées dans la presse. Je les découpe, les juxtapose, dessine par-dessus et les reproduis dans mon carnet de dessins et dans mes dessins préparatoires. On trouve des éléments ou des figures récurrents dans mes dessins, comme les uniformes militaires, par exemple ou, plus récemment, les cactus, parce que c’est plaisant à dessiner des cactus, et que cela me suffit pour les intégrer à un dessin. Je dessine des situations énigmatiques et ambiguës mariant le tragique et le burlesque. Ma pratique artistique consiste en ce que j’appelle des « formes dessinées », des articulations esthétiques et graphiques qui représentent l’indicible et, souvent, l’impossible. L’architecture de la composition comme forme de narration est aussi un élément essentiel de mon travail. Toutefois je demande un effort au regardeur, et ne livre pas tout.

Massinissa Selmani, la planete entre nos dents, 2021. Watercolor, coloured pencil on paper, 22 x 22 cm. © ADAGP Paris – Courtesy Galerie Anne-Sarah Bénichou, Paris.

C& : Dans une série d’œuvres récentes, vous avez eu recours à l’aquarelle. Dépassant votre palette de gris habituelle, vous réalisez des ajouts subtils sous la forme de couleurs vives qui transforment vos dessins.

MS : C’est exact. Adolescent, j’utilisais l’aquarelle, mais je n’ai jamais créé d’œuvres pour une exposition avec cette technique. Les couleurs ajoutent des couches à mes dessins. J’utilise les couleurs pour capturer l’attention des regardeurs et créer un équilibre entre le sujet et d’autres incidents.

C& : Des fragments textuels de poèmes viennent étayer des œuvres récentes. Comment avez-vous combiné textes et iconographie ?

MS : J’aime à dire que j’ai recours à une méthode surréaliste. On y trouve des mots de Paul Nougé, un auteur que j’ai découvert une fois adulte. J’aime l’humour dans l’écriture et les photographies de Nougé, la puissance transformatrice de son langage et son attitude envers l’exploitation du langage. Les mots de Nougé ont été utilisés pour nommer mes nouvelles sculptures en écho aux scènes représentées dans mes dessins. La littérature francophone algérienne a aussi influencé mes œuvres, tels que les poèmes de Jean Sénac. Je trouve son écriture très puissante. Le titre de l’exposition que je prépare à la galerie Anne-Sarah Bénichou à Paris, « Rien sinon du rêve au doigt » est un hommage à sa poésie. Ce vers est extrait de l’un de ses poèmes intitulés Trouvure. À la fois énigmatique et poétique, il met à nu un sentiment de violence inéluctable. Pour moi, les titres font partie de l’exposition ; ils ne donnent aucune indication ; ils sont volontairement énigmatiques et captivants et reflètent ce que sera l’esprit de l’exposition.

TROUVURE

Rien sinon du rêve au doigt

La sourde paix de l’effroi.

Massinissa Selmani: Rien sinon du rêve au doigt visible jusqu’au 27 juin 2021 à la Galerie Anne-Sarah Bénichou à Paris. (REPORTÉE!)

Massinissa Selmani est né en 1980 à Alger. Il vit et travaille à Tours, en France, et à Tizi Ouzou, en Algérie. Après des études en informatique en Algérie, Massinissa Selmani obtient son diplôme de l’École supérieure des beaux-arts de Tours. Son travail a été salué par une mention spéciale du jury à la 56e Biennale de Venise en 2015. En 2016, il a été lauréat du prix Art collector et du Prix SAM pour l’art contemporain. Il a participé à de nombreuses expositions personnelles et collectives en France et à l’étranger.

Elisa Pierandrei est une journaliste et auteure vivant à Milan.

More Editorial