The bold and groundbreaking exhibition project Living On, curated by Delal Isci and Thiago de Paula Souza, spans colonial, popular, and material histories, writes Ruby Jana Sircar

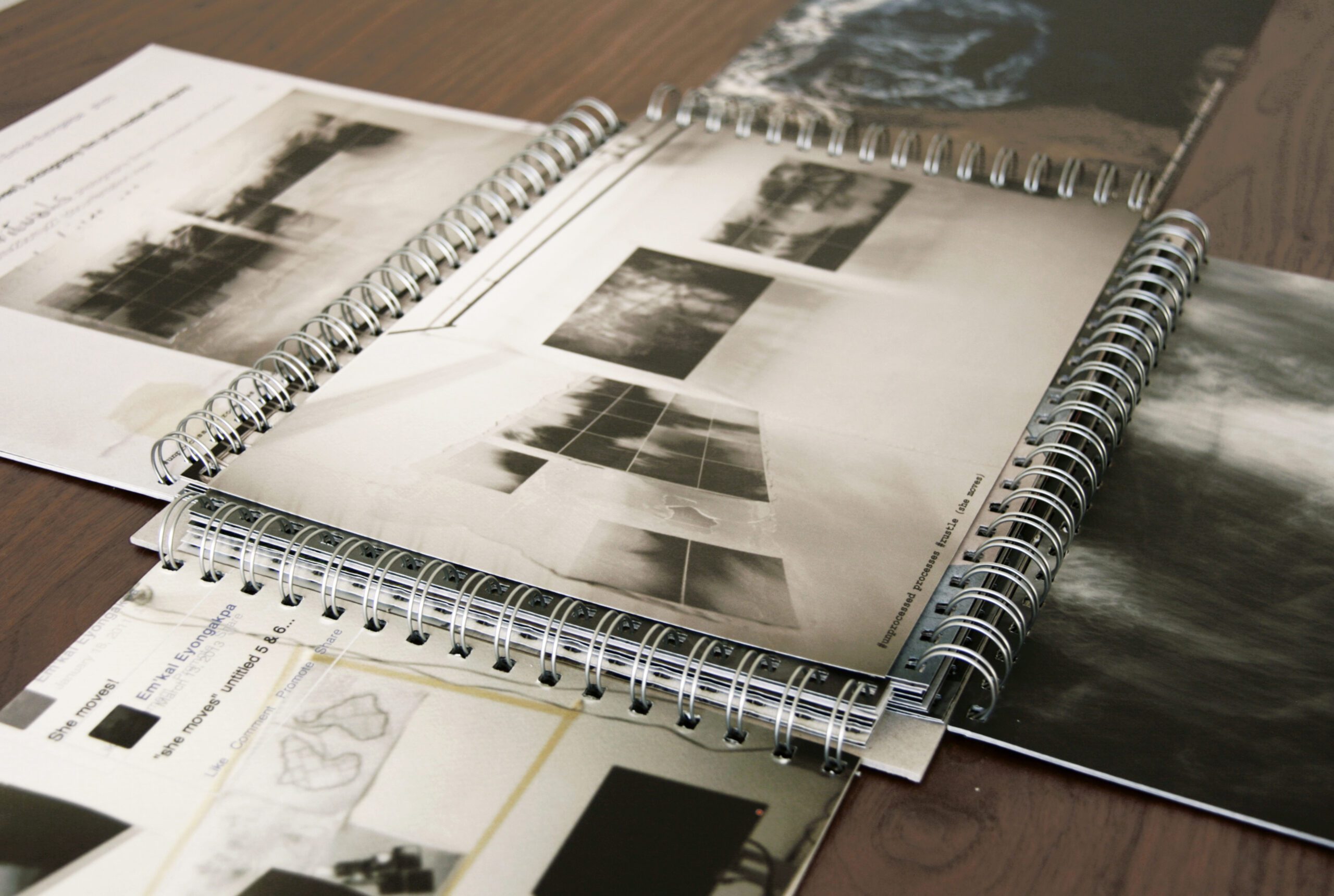

Em’kal Eyongakpa, BE-side(s) work- Em’kal Eyongakpa, friends and traces, 2014-2009, artist book, 2014, 112 pages, full colour, Stucco Fedrigoni paper, printed and bound in Italian. Courtesy of the artist and Boîte Editions, Lissone (IT)

.

The bold and groundbreaking exhibition project Living On, curated by Delal Isci and Thiago de Paula Souza, spans colonial, popular, and material histories. The project desynchronizes art history by showing work from the Austrian colonial painter Thomas Ender (1793-1875), with his perspective on the colonizing powers’ early landscaping and urban experiments in Brazil, to contemporary popular anthropological projects questioning material, documentary, and decolonizing positions. Furthermore, they simply negate Western supremacy and privilege and image narration by not allowing Western art history or philosophy to be the center of common understanding. The curatorial team clearly sets its narrative in the Global South: Between Clara Ianni’s questioning of power and governance in the modernist movement in Brazil to Tracey Rose’s discussion of racial and sexual hierarchies in South Africa and her questioning of pictorial techniques.

The exhibition unfolds in three chapters: Living On, Colonial Wound/Ghosts/Bodies, and The Economy of Oil. The essence of each is nevertheless present in all three: a search for popular myths, an understanding of shaping and accessing the natural as perceived by the colonial past, and an attempt to find ways to undo it with methods gained outside a Western academic knowledge production system. The question that might now arise is: How should such a display read by a mainly Western public in Central Europe? Perhaps one needs to look at the recursions and multiple-readings that such circumstances create. The audience is invited to erase its imagined common memory of an art-historical or popular-historical narrative and listen to the knowledge of decolonized masses who are otherwise perceived as silent.

Installation view Living on. xhibit, Akademie der bildenden Künste, September, 2016. Photo: Lisa Rastl

We might compare it to Salman Rushdie’s analysis of The Wizard of Oz (1992). Rushdie describes here the perception of a film – in the West an oddball, in post-colonial India a reality (1992:11). The film is a classic today, unquestionably a great colonial piece that deconstructs itself when read in a post-colonial setting. Nature and body, enslavement and decolonization are at the project’s core. This is clearly addressing the local public who is drawn in when entering the main room of the exhibition. The drinking-straw crown, a popular anthropological piece by the Producers of Kayapó, overtly resembles the Mexican penacho, a feather headdress on show at Vienna’s Ethnological Museum. The piece reignited disputes on ownership and restitution in 2012, as well as colonial responsibility in Central Europe.

Another easy point of access is granted by Lorenz Helfer’s work relating to colonized landscapes and contrasting the Brazilian rainforests with native Austrian forms and objects. Both landscape and object depictions are drawings. Both landscapes were economically used by colonial powers – albeit within different valuation systems and forms of material gain: alpine tourism and its roots in nineteenth century, British-originated, Romanticism and Brazilian indigenous knowledge and flora against a storm of missionaries.

Installation view Living on. xhibit, Akademie der bildenden Künste, September, 2016. Photo: Lisa Rastl

The display in which the art and anthropological work of the exhibition unfolds is clear-cut and addressed almost viscerally by the curators with their overall theme of natural and constructed worlds against colonial governance and supremacy. The playful depiction of Ender’s phallic aqueduct in the Brazilian moist landscapes and sweating enslaved bodies laboring in nineteenth-century South America is a comment on post-slavery conditions during Brasilia’s construction in the 1950s by Clara Ianni. Monira Al Qadiri’s Behind the Sun is seen as a post-religious and apocalyptical natural-resource game.

The project successfully embraces various media – from drawing, documentary film/video, and installation to anthropological objects and magazine production. Nossa Voz, a Jewish-Brazilian art publication, focuses on the main fields of discourse opened up by the project and for the first time grants access in English to historical Brazilian texts. The cultural translation work conducted by the project is eye-opening. Its simple beauty and quietly configured space allows the public to place and fill their own imaginations and images into the gaps which are the question marks posed by the curatorial team: What is decolonisation in a post-human world? What are the privileges within such a setting for future agents? Who is writing an artistic and cultural history for the future? The questions are also posed by another ongoing exhibition in central Europe: Okwui Enwezor’s Postwar – Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic 1945-1965 (Haus der Kunst Munich). Living On is the future of that exhibition.

Contributions: Thomas Ender, Em’kal Eyongapka, Lorenz Helfer, Clara Ianni & Clara Ianni in cooperation with Débora Maria da Silva, Juliana dos Santos, Nossa Voz, the producers of Kayapó, Tucano and Karajá, Monira Al Qadiri and Tracey Rose.

Ruby Jana Sircar is a media artist and a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

More Editorial