In a new series, C& is revisiting the most discussed, loved, hated, thought-provoking, and game-changing exhibitions featuring contemporary art from African perspectives in the past decades. We start with the (in)famous exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, which remains polarizing as a subject of curatorial and art-historical debates.

Entrance to the exhibition Magiciens de la terre. Retour sur une exposition légendaire at the Centre Pompidou, Paris 2014 © Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

“…this will be the first truly international exhibition of worldwide contemporary art.”(1) With Magiciens de la Terre, curator Jean-Hubert Martin had set out to do nothing less than that. In 1989 he presented works by more than one hundred artists from fifty countries at the Centre Pompidou and the Grande Halle at Parc de la Villette in Paris. To this day the legendary show is still disputed and has lost nothing of its relevance.

And in 2014 it was back. Twenty-five years after the exhibition’s opening, the Centre Pompidou revived Magiciens de la Terre in the form of an archival exhibition flanked by panel discussions. Allegedly only barely 300,000 visitors came to see the exhibition in 1989.(2) The corresponding catalogue was never translated into English. All the more surprising, how much attention and criticism the show elicited at the time. And to this day, Magiciens de la Terre is the subject of curatorial and art-historic debates that are rare when it comes to an exhibition. The reason: it caused the solid framework of Eurocentric art history to sway – irretrievably.

.

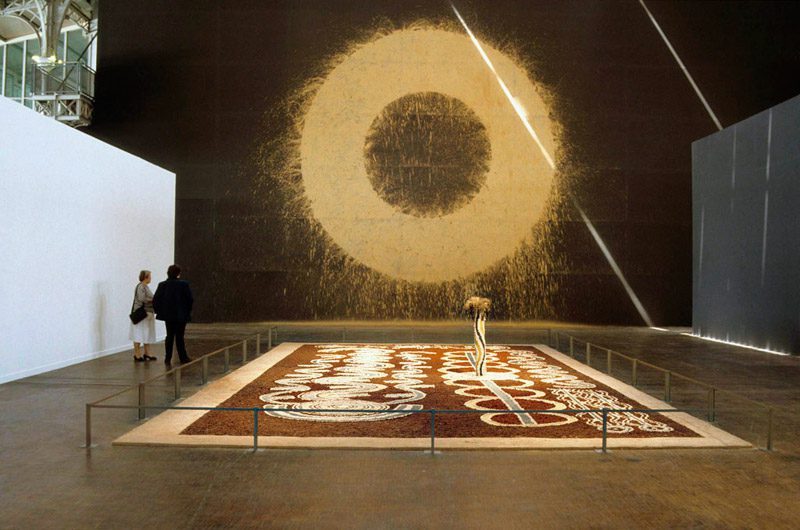

Magiciens de la terre at the Grande Halle, Parc de la Vilette, Paris 1989 © Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

.

Concept and criticism

Exactly half of the 104 exhibited artists came from so-called “non-Western” countries, including artists that are well-known today, such as Chéri Samba or Bodys Isek Kingelez. With a team of advisors the curator travelled to all five continents, visiting both academically trained and self-taught artists on site and not yielding to a discrimination between art and crafts in his selection of works. Magiciens de la Terre wanted to do away with the monopoly of European-American art and its narcissistic perspective. Instead, the exhibition was to describe artistic practice as a universal and spiritual phenomenon in a global world. In the catalogue, a kind of atlas of this global art world, each artist’s geographical background was marked on a folded out globe. Due to a shift in the display of the continents, the respective place was always located in the centre of the world – a metaphoric call for a new geography of art history. With his curatorial practice Jean-Hubert Martin wanted to clearly dissociate himself from William Rubin’s exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art. Affinities of the Tribal and the Modern, which was presented in 1984 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. While according to critics in this show the non-European objects were mainly exploited as proof for the genius of privileged “Western” artists, with Magiciens de la Terre Martin postulated unconditional equality of all artists in this world.(3)

Martin’s ambitious project not only brought him acclaim but was fiercely debated in two camps. One side saw Magiciens de la Terre as a threat to their “Western” modernity, their Hegelian worldview, which needed to be defended. The other criticised the way Martin dealt with religious or ceremonial artefacts, judging them through the lens of “Western” aesthetic standards. The curator classified them as works of art without taking a closer look at their function, thereby ignoring an essential part of their meaning. His search for the authentic and spiritual dimensions of art was also held against him. Quite often the curator selected a supposedly “traditional” artist or favoured the “originality” of a self-taught artist – but only in respect of “non-Western” art. The voices of professional artists went unheard. By imposing the role of the counterpart to academic Western art on the art of “non-Western” countries, the curator reinforced its exotic image of “primitive” folk art.(4) So was Martin’s concept no more than a fragile gesture of equality? As much as the curator distanced himself from Rubin’s exhibition, critics readily equated his approach with Rubin’s neo-colonial attitude.

.

Traditional paintings by the Yuendumu (aboriginal community in Australia) and in the background ‘Red Earth Circle’, a work by Richard Long at the Grande Halle, Parc de la Villette, Paris 1989 © Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

.

Relevance

“It was a major event in the social history of art, not in its aesthetic history.”(5)

The momentousness of the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre is beyond dispute, even though the concept certainly seems inadequate and outdated by today’s standards. At the time, the curator himself believed the show to be the first attempt to transform the “Western”-dominated art world.(6) Not despite but precisely because of all the criticism the exhibition ushered in a new era that progressively democtratised and decentralised the art discourse. Not least it was political turmoil such as the Fall of the Berlin Wall or the gradually crumbling apartheid regime that consolidated the exhibition’s geo-political significance and initiated new exchange and encounters in the art world.(7) It was only over the years, it seems, that the exhibition took full effect: today, Magiciens de la Terre is regarded as the birth of the so-called “global turn”, as the incentive for numerous exhibitions that have since undertaken a post-colonial re-writing of history, for instance Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa or Africa Remix. After “Primitivism“ in 20th Century Art it gave the starting signal for seriously exploring post-colonial approaches to curating and emphasised the need for a global art discourse.

Today, more than 25 years after Magiciens de la Terre, the globalisation of the art world is the height of fashion; it is the season of biennales, nomadic artists, and interconnected curators. But despite our world seeming to have moved closer together, the exhibition still inspires debates on our global society, its geo-political power relations and hierarchies. Magiciens de la Terre is not just a momentous piece of art history. Probably the decisive factor for the ongoing discussion of the show in literature, at panels, and exhibitions is that its demand for an equal and undivided (art) world to this day has not been consistently satisfied. Many of the questions that were raised are still waiting to be answered.

.

Works by Chéri Samba (Democratic Republic of the Congo) at the Grande Halle, Parc de la Villette, Paris 1989 © Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

.

Participating artists:

Marina Abramović (Serbia), Dennis Adams (USA), Sunday Jack Akpan (Nigeria), Jean-Michel Alberola (Algeria), Dossou Amidou (Benin), Giovanni Anselmo (Italy), Rasheed Araeen (Pakistan), Nuche Kaji Bajracharya (Nepal), John Baldessari (USA), José Bédia (Cuba), Joe Ben Jr. (USA), Jean-Pierre Bertrand (France), Gabriel Bien-Aimé (Haiti), Alighiero Boetti (Italy), Christian Boltanski (France), Erik Boulatov (Russia), Louise Bourgeois (France), Stanley Brouwn (Surinam), Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (Republic of Côte d’Ivoire), Daniel Buren (France), James Lee Byars (USA), Seni Camara (Senegal), Mike Chukwukelu (Nigeria), Francesco Clemente (Italy), Marc Couturier (France), Tony Cragg (UK), Enzo Cucchi (Italy), Cleitus Dambi (Papua New Guinea), Neil Dawson (New Zealand), Bowa Devi (India), Maestre Didi (Brazil), Braco Dimitrijević (Bosnia-Herzegovina), Nick Dumbrang (Papua New Guinea), Efiaimbelo (Madagascar), Nathan Emedem (Nigeria), John Fundi (Mozambique), Julio Galan (Mexico), Moshe Gershuni (Israel), Enrique Gomez (Panama), Dexing Gu (China), Hans Haacke (Germany), Rebecca Horn (Germany), Shirazeh Houshiary (Iran), Yong Ping Huang (China), Alfredo Jaar (Chile), Nera Jambruk (Papua New Guinea), Ilya Kabakov (Ukraine), Tatsuo Kawaguchi (Japan), On Kawara (Japan), Anselm Kiefer (Germany), Bodys Isek Kingelez (D.R. Congo), Per Kirkeby (Denmark), John Knight (USA), Agbagli Kossi (Togo), Barbara Kruger (USA), Paulosee Kuniliusee (Canada), Kane Kwei (Ghana), Boujemaâ Lakhdar (Morocco), Georges Liautaud (Haiti), Felipe Linares (Mexico), Richard Long (UK), Esther Mahlangu (South Africa), Karel Malich (Czech Republic), Jivya Soma Mashe (India) [in the catalogue but not in the exhibition], John Mawandjul (Australia), Cildo Meireles (Brazil), Mario Merz (Italy), Miralda (Spain), Tatsuo Miyajima (Japan), Norval Morrisseau (Canada), Juan Muñoz (Spain), Henry Munyaradzi (Zimbabwe), Claes Oldenburg (Sweden), Nam June Paik (South Korea), Lobsang Palden (Nepal), Wesner Philidor (Haiti), Sigmar Polke (Germany), Temba Rabden (Tibet) [in the catalogue but not in the exhibition], Ronaldo Pereira Rego (Brazil), Chéri Samba (D.R. Congo), Sarkis (Turkey), Raja Babu Sharma (India), Jangarh Singh Sharma (India), Bhorda Sherpa (Nepal), Nancy Spero (USA), Daniel Spoerri (Romania), Hiroshi Teshigahara (Japan), Yousuf Thannoon (Iraq), Lobsang Thinle (Nepal), Cyprien Tokoudagba (Benin), Twins Seven Seven (Nigeria), Ulay (Germany), Ken Unsworth (Australia), Chief Mark Unya (Nigeria), Coosje Van Bruggen (Netherlands), Patrick Vilaire (Haiti), Acharya Vyakul (India), Jeff Wall (Canada), Lawrence Weiner (USA), Ruedi Wem (Papua New Guinea), Krzysztof Wodiczko (Poland), Jimmy Wululu (Australia), Jack Wunuwun (Australia), Jie Cang Yang (China), Yuendumu (aboriginal community in Australia), Zush (Spain)

.

Julia Friedel is an independent curator and writer, living in Offenbach am Main. She studied African languages, literature and art (Bayreuth) and curation (Frankfurt am Main).

.

(1) Martin in Buchloh, 1989: 211.

(2) See Cohen-Solal, 2014; this is a comparatively poor attendance for the Centre Pompidou.

(3) Cf. Buchloh, 1989: 152.

(4) Cf. Poppi, 2003: 4-5.

(5) McEvilley, 1990: 157.

(6) Cf. Buchloh, 1989: 211-213.

(7) Cf. Cohen-Solal, 2014.

.

Further reading online:

Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, 1989: The Whole Earth Show

https://www.msu.edu/course/ha/491/buchlohwholeearth.pdf

Annie Cohen-Solal, 2014: Revisiting Magiciens de la Terre

http://www.stedelijkstudies.com/journal/revisiting-magiciens-de-la-terre/

Thomas McEvilley, 1990: The Global Issue

https://www.msu.edu/course/ha/491/mcevilleyartandotherness.pdf

Cesare Poppi, 2003: African Art and Globalisation

http://docenti.lett.unisi.it/files/40/3/1/1/Cesare_Poppi.pdf

More Editorial