As part of our Biennale-short-series Sabrina Moura sets the scene in her discussion of the Biennales in Dakar and Havana

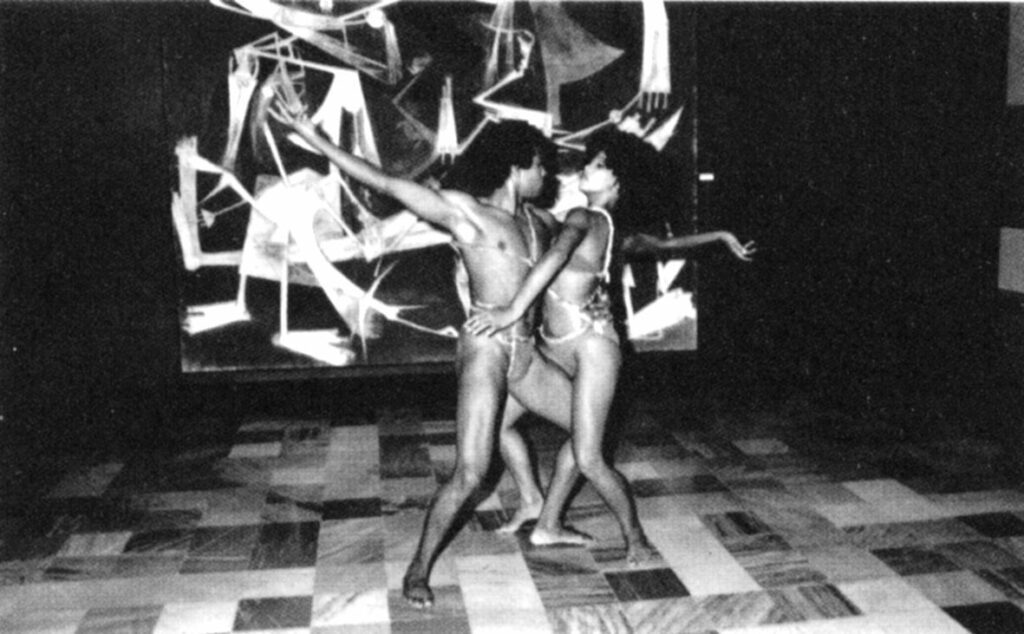

The Third World (1965), Wifredo Lam, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana

In the 1960s, two countries separated by the Atlantic assumed new political alignments, taking the field of arts and culture as a crucial axis of their national projects. On one side, recently independent Senegal sought its modernity under the sign of Négritude as fostered by président poète Leopold Sedar Senghor, and aimed to become a cultural exponent on the African continent. On the other, Cuba founded a revolutionary state where the emergence of an orthodoxy centered on the aesthetics of socialist realism was felt as a threat by a group of artists and intellectuals.

Despite their political differences, the founder impulse of their cultural agendas allowed Cuba and Senegal the establishment of a number of new programs and institutions dedicated to the arts including schools, festivals and museums(1). These institutions focused not only on the development of a local audience, but also shared a strong internationalist agenda that aimed to be progressively independent from Western tutelage.

These seminal cultural policies forged the conditions for the creation of the Biennials of Havana and Dakar between 1980 and 1990. Separated chronologically by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, both shows sought to renew the templates of cultural exchanges inherited from the colonial experience and, later on, from the Cold War. Both platforms adopted agendas that revealed a new relationship between biennials and State. For instance, the Havana Biennial was founded in 1984 under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture to “ensure a new importance to Cuba within Latin America, as well as in the Eastern bloc” (2). Likewise, the Dakar Biennale was created in 1990 under the mandate of the then-president Abdou Diouf in response to pleas from Senegalese artists and intellectuals for the state to take action in promoting a pan-African platform for the arts.

Performance facing the Third World painting by Wifredo Lam at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1st Havana Biennial, 1984 (Credits: Memórias de la Bienal de la Habana, Lilian Llanes, 2012)

They call upon the head of State to fulfil the role of a champion of the arts (as provided for in the constitution), citing the work of former president Léopold Sédar Senghor, who supported culture, in a reference to the past glory of the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres, held in 1966, a symbol of the continent’s creative and intellectual vitality and of Senegal’s ability to step forward to speak on behalf of the entire continent. (3)

Whereas the Havana Biennale promoted a third-world rhetoric in the arts field, which somehow responded to the ambitions of Cuban soft power, the Dakar Biennial set out to position itself in relation to the Senghorian dialectics of enracinement et ouverture(4). Both Biennials challenged the referential place of Euro-American modernity and contemporaneity in the arts.

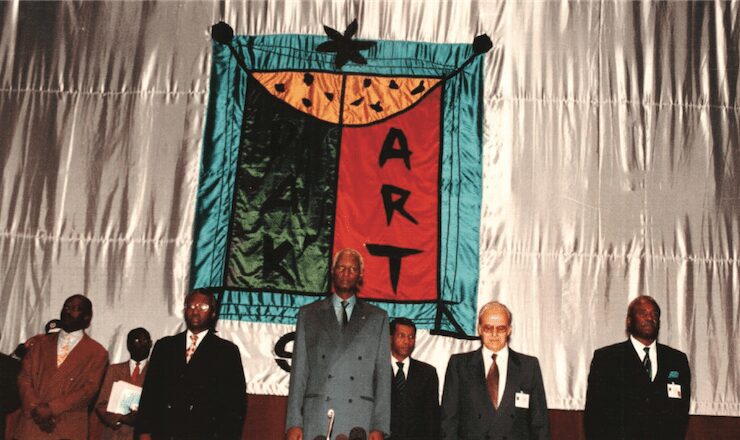

Opening Ceremony of Dak’Art 1996 Daniel Sorano Theatre Dakar 1996 President Abdou Diouf is standing in the middle Courtesy of Dak’Art Biennale Secretariat

The Havana Biennial initially restricted itself to Latin-American and Caribbean art production, but gradually broadened its curatorial scope to include art from Africa, Asia and the Middle East. This trend culminated in the iconic Third Havana Biennial (1989) entitled Tradition and Contemporaneity in the Arts of the Third World, whose exhibition project was aligned with a geopolitics of the arts that rose to prominence in the 1980s. Three years later, Dakar would open the doors of its first biennial with a proposal of alternating between literature and the fine arts. This concept soon gave way to the iteration that was eventually dubbed Dak’art, and whose focus turned to various visual art languages with no restrictions of nationality. Unlike Havana, Dakar embraced a regional perspective that is essentially focused on the African art community and its diaspora, a pan-African mission, as explained by Yacouba Konaté, curator of the seventh Dak’art:

The Dakar Biennale claims the promotion of African artists in general as its trademark. Since 1996 it has presented itself as the pan-African biennale of the arts. In positioning itself as such, Dak’Art takes as its center of gravity the entangling of the overall history of the Dark Continent with the microhistories, edifying to varying degrees, of individual and collective subjects who identify either in full or in part with its destiny while at the same time causing it to move—a little like the man who both carries and projects his shadow as he walks. Dak’Art lifts its head and speaks for Africa and in the name of Africans.(5)

Through advocating contexts and exhibition frameworks for non-Western artistic production, these biennials help us rethink established categories in the realm of art history, including temporal and geographic markers, such as the idea of essential identities that seem to permeate concepts of African and Latin American art.

In this series we will address a number of questions that arise from the intersection of such cultural projects: What do artistic exchanges between these Biennials reveal about the cultural networks connecting Africa and Latin America? How do these exhibition strategies converse with emancipatory ideologies and projects such as anti-imperialism, pan-Africanism, third-worldism, and the notion of the global South? How does Havana deal with African art production; and what role is reserved to art from the diaspora in Dakar?

Sabrina Moura is a curator and editor based in São Paulo (Brazil). She is currently a PhD Candidate at the History Department at the University of Campinas.

(1) Initiated in 1959, post-revolutionary Cuban cultural policies founded institutions such as Casa de las Américas, the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), the Orquestra Sinfônica Nacional, among others. Under Senghor mandate’s, Senegal hosted the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres, and founded the Musée Dynamique, the Théâtre National, the École des Arts du Sénegal, among other institutions.

(2) Belting, H et al.The global contemporary and the rise of new art worlds, 2013. Also refer Rojas Sostelo, M. The Other Network: The Havana Biennale and the Global South, The Global South, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2011.

(3) Pensa, Iolanda, La Biennale de Dakar comme projet de coopération et de développement, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, 2011.

(4) Abdoulayé Wade, Catalogue of the 5th Dakar Biennial , 2002, 5.

(5) Konate, Yacouba. “Dak’Art: The Making of Pan-Africanism & the Contemporary.”Art in Translation 5:4, 2009, 487-526. Also refer to Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi’s and Cédric Vincent’s writings on Dak’art, which include Contemporary& special issue on this biennial (printed version, no. 1, April, 2014).

More Editorial