Commune.1, Cape Town, SA

26 Nov 2015 - 21 Jan 2016

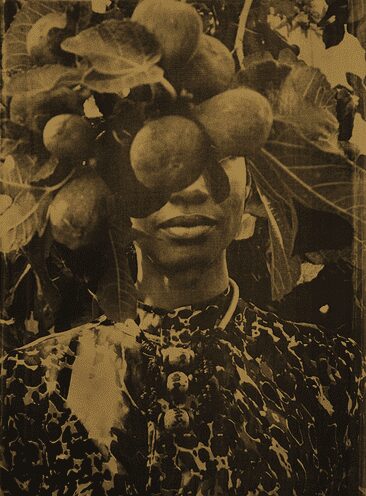

Ficus Carica. Courtesy Zohra Opoku

Commune.1 has just opened ‘But he doesn’t have anything on!’, an exhibition bringing together a group of contemporary artists who employ the visual language of textiles as a tool to explore expressions of individual, cultural, political, and social identity. The title of the exhibition is taken from Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, a well-known tale about a vain king tricked by swindlers into wearing a suit of the finest invisible fabric. All the king’s ministers and town’s folk keep up the pretense until a child breaks the illusion by exclaiming: ‘But he doesn’t have anything on!’ The tale migrates across various cultures reshaping itself with each retelling in the manner of oral folktales.

With Dominique Edwards, Rory Emmett, Susan Greenspan, Bonolo Illinois Kavula, Olivié Keck, Namsa Leuba, Troy Makaza, Siwa Mgoboza, Simphiwe Ndzube, Zohra Opoku, Thabo Pitso, David Southwood, Lauren Webber

Historically and in the now textiles have had a significant influence on South African and African art practice. Currently this woven entity is being engaged in a variety of ways: as a tool to conceal or reveal identity, to subvert or challenge authority, to reclaim history, to camouflage, as a placeholder for the corporeal body and to bring about an ideological transformation.

Centre stage is Dominique Edwards’ large-scale ornate tassel constructed out of mop yarn. Conceptually this sculpture follows on from Edwards’ solo exhibition in early 2015 wherein Edwards hand made paper from used and new mops and installed a 3-metre diameter mechanised mop in the gallery. Themes of cycling and recycling appear in her reconstruction of seemingly banal domestic items into art objects. Edwards has an ongoing interest in the repetitive activity of human labour, and is particularly curious about the materiality of things and how they retain their form. This addition to exhibition has an inherent playfulness and responds lightly to the story of the Emperor’s New Clothes.

Animal hair provides the starting point for Bonolo Kavula’s new installation. The short video, ‘Bo-Peep’ (2015), shows the artist shaving hair off sheep’s hooves, albeit somewhat clumsily. This performed task provides a reference point for the rest of the installation consisting of patchwork canvas and framed prints. As in previous installations, Kavula’s focus remains on unveiling and concealing and, like Edwards, she employs seemingly ordinary objects in new and unexpected ways. The current installation shows a move from printing on paper to canvas. Kavula’s process is layered and considered: borrowing the canvas from a long tradition of painting, she rips the material off its stretcher frame and then draws on it with permanent markers and pens. The marks made by the pen represent the fine hairs removed from the sheep hooves. The same lines are also carved on a lino-block, which is printed onto the canvas. The resulting abstract and tactile canvasses are strangely fabric like, existing somewhere between muted ikat and animal-hide.

Zimbabwean based Troy Makaza’s surreal works woven from painted silicone are also singularly medium-defying; the strings inhabit the space on either side of painting and sculpture. Threadlike spider webs of hair, accented with bands and braids of brightly coloured silicone, are part of Makaza’s broader examination of the fluid and in-flux relationships between the sexes in contemporary Zimbabwe. The twisted strands bound together build powerful metaphors for social and intimate spaces, where traditional roles are no longer assured and liberal attitudes don’t always belong.

From the beginning of her practice Boston born Lauren Webber has been concerned with the affect of Christianity (amongst other religions) on women. Since arriving in Zimbabwe in 2014 she has been struck by the heady mix of contemporary Zimbabwean spirituality: syncretic practices, the aftermath of colonialism and charismatic evangelicals. In her new work, she transfers religious and colonial symbols onto polycotton found in Zimbabwe. Using cloth adorned with religious symbols for denominational distinction is a uniquely African tradition, adapted by the missionaries for facilitating conversion. Using this adaptation as her point of departure, Webber reflects on Christianity’s pandemic march around the world, with its widespread political and social implications.

Namsa Leuba’s photographs aim to counter-distort the exoticisation of African identity by the Western gaze. With a Guinean mother and a Swiss Father, Leuba is locked in a permanent struggle as she attempts to reconcile a personal sense of cultural syncretism, and to question the ambiguity inherent in ethnocentrism. Leuba’s award-winning project, Ya Kala Ben (2011) was captured on a trip to Guinea Conakry during her degree at Lausanne. In this body of work Leuba looks at ritual artifacts common to the cosmology of Guineans, or rather statuettes that are part of a ceremonial language of Guineans. She then re-contextualizes these sacred objects with her lens bringing them into a framework meant for Western aesthetic choices and taste, as explained by Leuba: ‘These objects are part of a collective that they must not be separated from, or risk losing their value. They are not the gods of this community but their prayers. They are integrated in a rigorous symbolic order, where every component has its place. They are ritual tools that I have animated by staging live models and in a way to desecrate them by giving them another meaning; an unfamiliar meaning in the Guinean context.’

Siwa Mgoboza’s photographic constructs manifest his ‘post-post-colonial’ world called AFRICARDIA. He has imagined this future land’s physical landscape, its inhabitants and animal-life. Here nature and humans live side by side peacefully, the world of difference does not exist and hybridity is taken to new levels of boundless subjectivity. Mgoboza’s frenetic compositions are a reflection on what it would be like if a cosmic clash occurred and beings of AFRICARDIA were teleported to our current reality. The use of Isishweshwe is instrumental. This well-known fabric has a loaded history: of trade and cultural interchanges across the continent; of indigenisation, cultural revitalisation and re-appropriation. The history of wax printed material is a history of colonial trade that saw material culture trafficked through imperial powers to their colonised subjects. The material speaks of the colonial trade route whose conclusion is integral to a particular sense of African identity after liberation from colonial authority.

It took 3 trips for David Southwood to complete his Lesotho portraits and landscapes to his satisfaction. He initially went to Lesotho to photograph the Basotho herders living on the Katse Dam in their traditional balaclava headgear. Being sensitive to questions of privilege and power in relation to portraiture, Southwood explores the significant conundrum of photographing faces obscured by woolen hats. After the balaclava series, Southwood shot a series of herders wearing blankets, ‘Tanki Mphongoa’ (2015) is one image from this series. The wearing of the blankets relates to a single incident in which a certain trader, Mr. Howel, presented King Moshoeshoe I with a blanket in 1860. Since then blankets have come to indicate coming of age, marriage phases and ceremonies and each particular configuration of inherited colonial insignia adds to a further layer of meaning.

‘Looking up to the sky, searching beneath the ground’ (2015) emerged as an extension of Simphiwe Ndzube’s graduate body of work Imithungo Yezivubeko. The title is in isiXhosa and can be interpreted as ‘stitches of remnants’, or ‘stitches of internal and external scourges of the past and present’. It makes reference to the process of stitching that Ndzube employed throughout the show, and that informed his research, in Ndzube’s own words: ‘It has allowed me to negotiate a way through many objects, memories, past and present events in order to stitch together an account of the experience of being black in the post-apartheid South Africa that is haunted by the unresolved burdens of the past. There is a certain violence inherent in the cutting and stitching, the pulling together of thread, and the assembling of objects and articles of clothing on canvas to invoke a body fraying at the seams. The distorted forms that emerge reference the multiple violences to which the black body is exposed, and also stand in for Africa more broadly, used as the dumping ground for cheap clothing imported from the West and emerging Chinese markets. These imports constitute a secondary violence directed at the growth of African industry, and negatively impacting the domestic textile industry.’

Similarly Thabo Pitso’s sculpture ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ (2015) comments on the plight of South Africa’s textile workers. The work seeks to represent the journey of those that have been affected by the collapse of the textile industry in South Africa, in particular the Western Cape. The suitcase containing burnt clothes and shoes speaks of the closed down factories and how many of the workers were forced to pack their bags and return to their homes. Utilizing assemblages of found objects to construct sculptural installations, Pitso’s work deconstructs the social and personal meanings of objects.

Zohra Opoku’s photographs and videos unpack the political and psychological role that fashion plays in influencing the psyche of individuals and the socio-cultural dynamics underlying consumption. Throughout the year, Opoku has been interested in the diversity of plants in the San Francisco Bay area where there are a huge variety of non-native plants from different climates grown in so-called plant communities such as dunes, grasslands and forests. The series included in the exhibition follows on from Opoku’s portrait series TEXTURES that focused on disguise and nature. After further contemplating the notion of self and the genre of portraiture, Opoku began her camouflage self-portrait series approaching it as a type of therapeutic conversation between the ‘I’ and ‘me’ wherein her ego seeks to achieve a self-reflexive identity. Opoku’s intellectual engagement and physical emersion in the unusual and exotic foliage found in the Bay area result in silkscreens wherein the artist is partially invisible and mentally in a state of absolute comfort.

‘Playground l (a brief history of Colourman)’ (2015) is a fantastical and imaginary installation created as a memorial to Rory Emmett’s constructed avatar, ‘Colourman’. This assembled museum display is made up of painted canvas and found images, from the artist’s own archive or thrift shops, in which Emmett has inserted his painted avatar. The installation aims to question the limited idea of ‘coming-of-age’ and is part of the artist’s ongoing attempt to define the ever-changing self in light of oppressive constructs, labels and descriptions. Drawing on personal, collective and art historical references, Emmett approaches painting as a means of viewing past and present landscapes and presents identities as constantly in motion. While Colourman’s skin belies his ‘nakedness’, his ‘Colouredness’ also works as a type of mask. Thick colourful blobs of paint form his skin, much like patterned clothing.

Olivié Keck’s glazed stone ceramic sculptures express themselves through the ‘costumes’ that they wear; patterns, tints and lusters add to the complexity of the finish. Like Emmett, throughout her practice Keck has ventured to decipher the transient natural world and her place within it and ‘I Ain’t Trippin’ On What Could Have Been’ (2015) is no exception. The sculpture stems from the artist’s frustration with the unpredictability of ‘the real’. A growing niggle that the physical moment lacks the luster of the manufactured ‘inner’ expectation of her mind. As explained by Keck: ‘This work attempts to address a growing concern I have around suffering from an inability to experience ‘joy’ in the moment. As an artist I feel I have gotten into a habit of documenting life from a bird’s eye view, a necessary skill, but deeply problematic. Increasingly I find myself criticising experience in all facets of life. It makes for compelling content/artwork, but it’s murder on personal interactions. I often feel inhibited by a genuine fear of missing out on living, and being crippled by ‘hindsight’.’ This inner conflict is evinced by the meditative state of the sculptural form.

Susan Greenspan’s nine digital images are a pertinent counter-point to David Southwood’s and Namsa Leuba’s photographs and Zohra Opoku’s silkscreens. The inkjet prints originate from marks made while retouching archival and documentary photographs. They highlight the digital and analog methods for correcting, erasing, and rebuilding that are commonly used for retouching. These marks on the image are always present, but hidden in the making of ‘realistic’ or ‘documentary’ images. Greenspan discards the original and leaves the marks for us to see. These abstract marks are thread-like in nature and metaphorically can be read as a blanket, or a mask, laid over the photographic document. This metaphor encourages us to unpack an art form laden with representative difficulties.

http://www.commune1.com/