A generation of Sudanese civil society reconvenes in Sharjah for a compressed, weekend-long reprise of a longstanding debate.

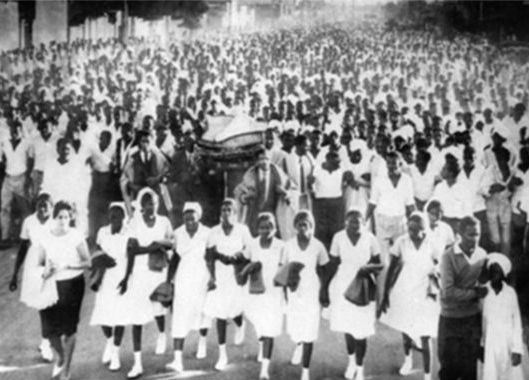

Scene from a Procession, October 21,1964 Revolution (Ahmad Al Qurashi’s Funeral). The Ministry of Culture, Republic of Sudan

A generation of Sudanese civil society reconvenes in Sharjah for a compressed, weekend-long reprise of a longstanding debate.

“Modernity and the Making of Identity in Sudan: Remembering the Sixties and Seventies” offered an eleventh-hour reckoning for Sudan’s cultural “golden age” and a generation of writers and artists who represent today both the period’s exhilarating promise and the unrelenting disappointments marring subsequent decades. The scope and ambition of the proceedings made this a landmark event. For the first time, many of the period’s main protagonists and their interlocutors convened in the same room to address questions that had critically shaped their respective careers and terms upon which the possibility (or impossibility) of a coherent modern Sudanese identity had historically been posited, namely a reconciliation of the country’s “African” and “Arab” identities.

The advancing age of some of this generation’s most influential figures threatens to cut short efforts at documentation and debate. The organizers succeeded in wringing every minute out of the two-and-a-half day symposium, packing in approximately 40 papers and presentations related to the history of film, theater, cinema, music, and visual art of the period. I met people I’d only encountered in books or on museum walls; the contours of a decades-long conversation unfurled before my eyes in real time. The situation’s poignancy was never more apparent than when Mohammed El Makki Ibrahim, author of the celebrated poem “Ummati” (My Nation) (1969), read some of his poems on stage while the audience recited his words along with him. Likewise, the charismatic solo presentations of artists Kamala Ibrahim Ishag and Amir Nour as well as theater director and playwright Shawgi Izzeldin Elamin elicited standing ovations and expressions of gratitude.

At the conference Modernity and the Making of Identity in Sudan: Remembering the Sixties and Seventies, Sharjah, 2015. Photo: Clare Davies

At other moments, however, this eulogy became an accusation: the symposium’s success was a bitter reminder to some of the failures of those in attendance, who, they believed, could have made a difference sooner. “This is how they should have run the country,” remarked the political cartoonist Khalid Albaih during a coffee break. Indeed, this sentiment echoed a conviction held by others I spoke to who believed that the Sudan’s contemporary history of violence could be blamed, in part, on the failure of intellectuals to formulate a felicitous understanding of modern Sudanese identity. “It is now widely acknowledged that the issue of Sudan’s cultural and political identity is one of the root causes of the Sudanese crises that has crippled the country since its independence in 1956 and plunged it into a civil war regarded as the longest in Africa,” wrote Mohamed Abusabib, another attendee, at the outset of his 2004 book Art, Politics, and Cultural Identification in Sudan. The secession of South Sudan in 2011 could not but represent the final collapse of former visions of a nation and national identity. In this regard, the stakes could hardly be higher.

The broad-strokes periodization that framed the symposium belied a more specific set of dates. Many participants pointed to the October Revolution of 1964 as a starting point that ushered in a brief window of relative stability and secular governance. Identifying an endpoint was more difficult and is perhaps better described not in relation to a particular moment, but rather as a confluence of events culminating in the consolidation of power within the hands of an authoritarian, Islamist government and the escalation of the civil war in the 1980s. With one exception, an oddly depoliticized study of Hassan al-Turabi’s “monotheistic” interpretation of identity and culture, this framework excluded any consideration of how Islamist rule in Sudan had informed cultural politics. Between 1964 and the 1980s, many of those present at the symposium had either held high-ranking posts in the government or been persecuted through imprisonment, forced exile, or other means (or had seen both favor and disfavor).

By and large, this symposium represented an extended conversation amongst a network of people who had known each other for many years and were intimately familiar with each other’s work. Perhaps as a result, there were few attempts to reconfigure or make explicit some of the broader terms and connections (for example the relationship between the so-called Khartoum School of visual artists and the literary School of the Jungle and the Desert [Madrasat al-Ghaba wa-l-Sahra’]) as promised by the organizers. Some speakers rehearsed litanies of significant historical events, while others presented in-depth readings of a particular literary work, reflected upon an important figure, or discussed a major problematic attending the relationship of “identity” to “modernity” in Sudan. The pace and intensity of the proceedings required nothing short of one’s full attention. A battery of dense, fifteen-minute presentations spanned a wide continuum of topics and was spiced occasionally (I was told) with coded references to longstanding quarrels.

Other axes of difference and disagreement were more explicit. A generational divide distinguished those who understood the postcolonial state as the only viable framework within which to develop cultural institutions (while also, at times, acknowledging its dismal track record in doing so) from those who actively sought alternatives. Tellingly, it was only the founder of a major art space in Khartoum whose easy relationship to the present status quo seemed to absolve him of the discomforts of self-interrogation and intellectual critique. Instead, he used his time on stage to screen a promotional video for his space, geared, it seemed, towards potential fundraisers, and ducked pointed questions from the audience regarding his hoarding of resources and exclusion of younger artists.

Two refrains recurred over the course of the three-day event in Sharjah: a call for self-criticism and the heralding of a new beginning for cultural discourse and practice in Sudan. Certainly, the organizers had knitted together various strands of a far-flung network spanning multiple generations and fields of practice with an eye to specific plans for the future. The event will serve as a platform for a series of exhibitions and publications co-produced by the Sharjah Art Foundation, directed by Sheikha Hoor al-Qasimi and the Institute for Comparative Modernities at Cornell University, headed by the art historian Salah Hassan. At least some of the participants seemed to feel the same way about the event’s potential as a catalyst for future initiatives while wondering how it might be possible to bring the conversation “back” to Sudan. Meanwhile, it was the younger writers and artists in attendance who offered the most powerful arguments for self-reflectivity as an urgent ethical question and an intellectual position.

In the fifteen minutes allotted her, Stella Gaitano deftly shuffled off the cumbersome Arab-North/African-South binary with a probing reflection on her reception as a “South Sudanese” who writes in Arabic. Gaitano was born in Khartoum and graduated from the University of Khartoum in 2006, only moving to Juba, the capital of South Sudan, after 2011. Despite this personal history, she noted with a smile, people often expressed amazement at her ability to write in Arabic. Picking up where she left off, the final speaker, novelist and literary critic Jamal Mahjoub, described himself as a Sudanese of Nubian origin who thought, spoke, and wrote in English. He had left Sudan with his family in the 1980s: a period that witnessed reversals, as he recounted, of everything his parents’ generation had worked for. The symposium organizers framed Gaitano and Mahjoub as representatives of a cultural present. If we take this proposition seriously, then, the “present” is no longer located almost exclusively in Khartoum; it exists in Juba, as well as the many capitals of the diaspora, not least Sharjah, where a number of Sudanese intellectuals of the 1960s–1970s generation held important posts in the cultural sector. The present is also critical of the role “identity” has played thus far in shaping cultural discourse and practice and unwilling to overlook the inconsistencies and violence inherent in its binary logic. Following the final remarks, all the participants got up on stage for a photo op. For a moment, the debate subsided. The audience rose appreciatively to its feet and clapped away. It felt like a curtain call for Sudan’s compelling, if contested, “modern” past and a salute to those shaping its present outside the lines prescribed for it by state institutions.

Clare Davies received a PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University in 2014 for a dissertation entitled “Modern Egyptian Art: Site, Commodity, Archive, 1891-1948”. She is the recipient of the inaugural Irmgard Coninx Prize in Transregional Studies 2014/2015, Forum Transregionale Studien, Berlin.

More Editorial