‘Biennials evade easy definition. There’s hybridity, and that’s the beauty in this field.’ Marieke van Hal talks about the criticism biennials face, and how the 21st century belongs to the global south. C& in talks with Marieke van Hal director of the Biennial Foundation.

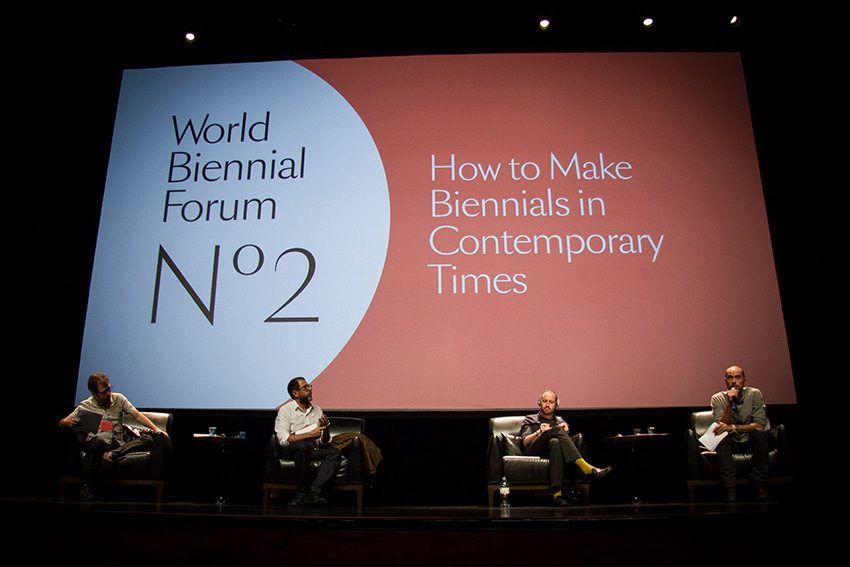

Panel Discussion: Once Again, as If for the First Time: archives, biennial memory and the balance between continuity and reinvention with Anthony Gardner, Fabio Cypriano, Fernando Oliva and Pablo Lafuente, moderator. Photo: Maycon Amoroso

C&: There are biennials all over the globe – some even seem to be “teaser” events to get the art world to travel further afield. Do we need biennials to direct attention towards those art scenes outside of Europe and North America, which are still marginalized by the international art scene?

Marieke van Hal: No, I don’t think we need biennials for this, as it implies a very superficial interest. That said, biennials are popular events capable of producing large audiences and usually, interesting transnational dialogues. At most biennials, and we tend to forget this very often, local communities form the majority of the public and not the traveling art world professionals even though they might are lead the critical discourse.

World Biennal Forum venue: Auditório Ibirapuera, Parque Ibirapuera São Paulo. Photo: Maycon Amoroso

C&: There are increasingly conversations around South–South connections in the art world. What are your observations of this within the framework of a “biennale”?

MvH: The North–South dialectic of post-colonialism is not over, but new, multilateral relations are emerging that reflect South–South dialogues in which the potential of exchange circumvents the North. We see this in the economic and political arena, and also in our professional field. But I’m not sure it’s something new. The history of biennials mostly comes from a northern perspective, whereas the southern perspective remains rather unexplored. Anthony Gardner, who participated in our World Biennial Forum, and Charles Green, are doing pioneering academic research in this. In a recent essay they studied biennials of the non-aligned nations of the South, and their conclusions show that many of the early so-called southern biennials sought to redirect the axis of cultural and economic influence away from the north. Most well known to us in this perspective is the Havana Biennial that has always focused its attention on artists from the south. Gardner and Green argue that it was an insistence on regionalism that has characterized most southern biennials, as well as a focus on horizontal axes of dialogue and engagement across a region. Today, an interesting case in this context is the Jogja Biennale in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Since 2011, the Jogja Biennale has been focused on encounters with nations in the equatorial area. The next edition (2015) is in partnership with Nigeria.

C&: Biennials are increasingly criticized with regards to their lack of content. Although they gather a high number of artists, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the exhibition transports a deeper or relevant message. What is your take on this?

MvH: The 31st Bienal de São Paulo, the host of our World Biennial Forum No. 2, could serve as an argument for the opposite view. This thought-provoking biennial conveyed a highly important message especially to Brazilian audiences, showing them what their biennial could also reflect, tell, or do. The Bienal de São Paulo incorporated a reaction to some recent editions of established biennials that returned to the museum as a model. This biennial was conceived during the mass protests and social uprisings in Brazil last year and invited artists to show the struggles of society, not only in Brazil, but also in other parts of the world. An important question was posed: how can art works, and the art world as a whole, reflect the demand for a turn in social, political, and economic environments? In a global art world where market forces strongly dominate, this curatorial team took a radical left-wing stance and proved that the biennial is not necessarily neoliberal. This was also very clearly reflected in the choice of artists.

Photo: Maycon Amoroso

C&: What was discussed during the World Biennial Forum 2 in São Paulo? In your view, what was the outcome of the meeting?

MvH: One intriguing outcome was the disagreement on what “south” stands for. One of our invited respondents, Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, asked if the south is a useful category for critical thinking? Dakar is north of the equator but is part of the “Global South” in terms of its political history; likewise, Australia is a northern outpost in the south. For most of the researchers participating in the Forum, south was regarded as a geo-political focus that relates to a certain history – tied to the struggle against colonization and the necessity of decolonization, and a need to create a counter-discourse to engage the hegemony. In one of the panels, the Greek curator Marina Fokidis represented the notion of the south as “a state of mind,” a more abstract or creative concept.

Another interesting outcome was the critique the Biennial Foundation received. It was the first time I realized some people see us as a so-called “global institution.” The critique focused on the fact that we were initiated in the west, and many voiced their fear that the ubiquity of contemporary art biennial threatens to topple over into homogeneity. The idea for Biennial Foundation started when I was directing the first Athens Biennial. It was difficult, and I felt the need to reach out to colleagues internationally to learn from and exchange with them. As such, mutual curiosity and shared interest are the basic drives of our activity. The Biennial Foundation doesn’t claim, or have, any authority. We saw a need and took initiative.

Workshops on Biennial Practice, World Biennial Forum No 2, 2014. Photo: Maycon Amoroso

C&: Where do you position biennials happening on the African continent, such as Dak’Art, which, although it has existed since 1992, received a bigger international reception last year than ever before?

MvH: International perception derives from an increased interest in contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora in general. Dak’Art is the most well-known biennial in Africa historically and the Johannesburg Biennale (now defunct) the most legendary, but as you know there’s a lot more going on today. I’m thinking about the biennials of Lubumbashi, Marrakech, Benin, Luanda, Bamako, São Tomé e Príncipe, and Kampala. How to position them? Perhaps like any other biennial? Elvira Dyangani Ose beautifully spoke about her experience with the Lubumbashi Biennial “Rencontres Picha 2013,” taking precariousness as the organizational principle and imagination as an asset central to it all. From what I have seen around the world, it is that precariousness and imagination as well as experimentation that are inherent to each biennial.

Photo: Maycon Amoroso

C&: There is the idea to maybe organize the next World Biennial Forum on the African continent. What effect do you think that could have on the local biennials, art scenes, etc., on the continent?

MvH: We are informally talking with art professionals from Africa about feasibility. The first edition of our World Biennial Forum, “Shifting Gravity,” took place in Gwangju, South Korea in 2012, and focused on Asia as a context and continent. The World Biennial Forum No. 2, “How to Make Biennials in Contemporary Times,” just closed in São Paulo, Brazil, and it examined the biennial from the point of view of the Southern hemisphere. It could create an interesting triangle to move to Africa now but nothing is confirmed and other options are also being explored. The two editions so far have been quite different. Sean O’Toole wrote in the context of the current interest in contemporary art from Africa “that artists not geographies should be our focus” and perhaps this can be a good leitmotif for a next Forum. Artists have been hugely left out of the discussions to date and this is something that needs to be worked upon.

C&: What do you think can sustain alternative more recent biennials such as KLAART in Kampala, the Marrakech Biennale, etc., on the African continent?

MvH: Sustainability is a big issue. Many contemporary art initiatives and biennials in Africa are supported by western agencies, whereas long-term survival and sustainability depends on support from the localities eventually. A question that interests me is what these western funding streams mean and how they fit into post-colonial narratives. At the same time, in Europe the arts sector is buckling under the strain of budget cuts. In our practice, it is sometimes easier to fundraise for someone from Africa, the Middle East, or Latin America than for an Italian, a French person, or a Dutch person. The twenty-first century belongs to the south, it seems.

The World Biennial Forum No. 2, “How to Make Biennial in Contemporary Times,” took place from 26–30 November 2014 in São Paulo.

.

Interview by Yvette Mutumba

More Editorial