Artist Mostafa Maftah caught up with our author Elsa Guily to talk about the cultural heritage around the skills of weaving carpets (zarabi) as a medium of social dynamics and conditions.

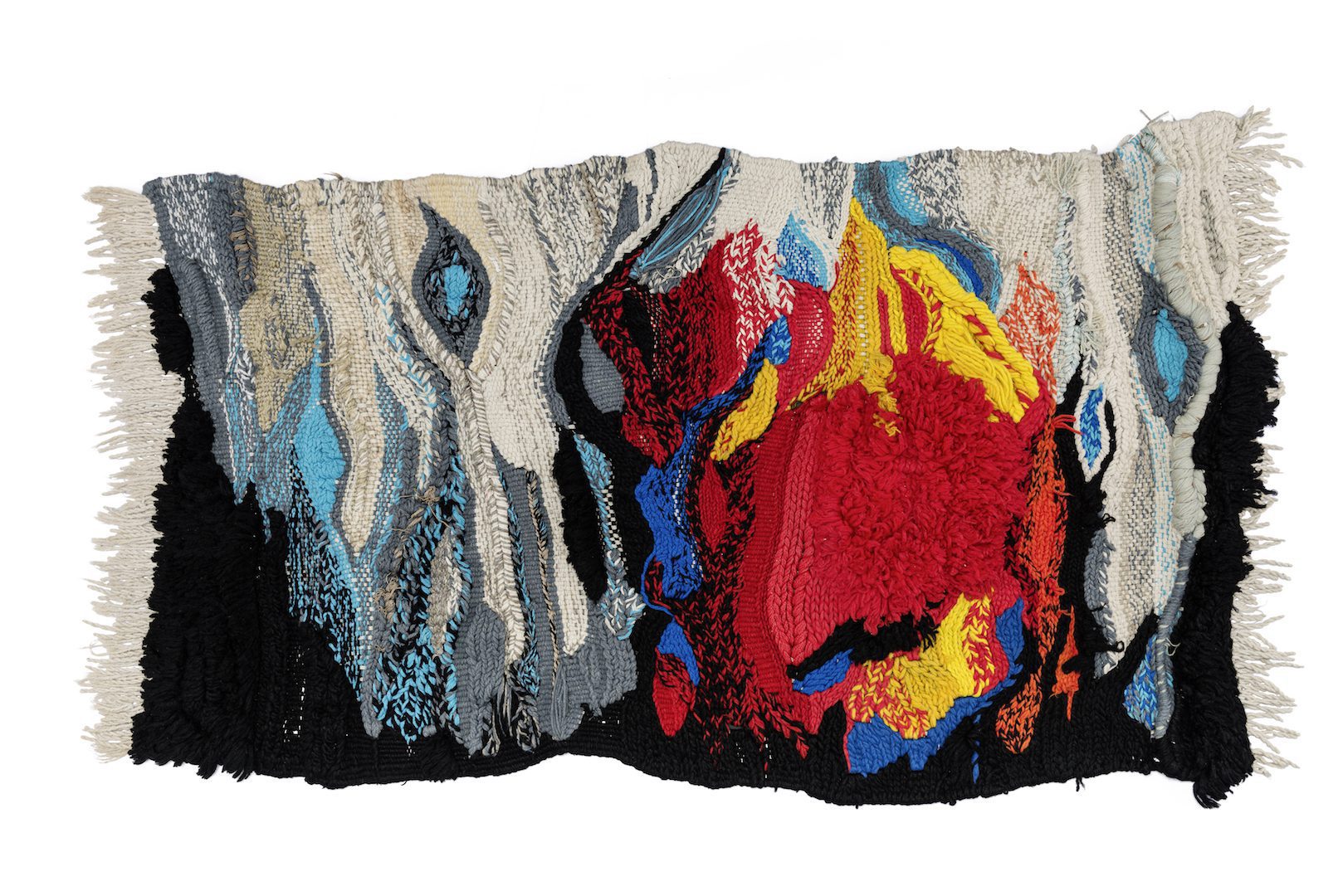

Mosta Maftah: Fire in the Ocean, 1979. Wool, Silk, Cotton. © Courtesy of the Artist and Thinkart, Casablanca

Mostafa Maftah never stops threading and twisting the text of artistic modernity, which remains in a constant state of renegotiation. The zlāg gesture of Feu Océan (Ocean Fire, 1979) unravels the West’s canonical seams of categorization to re-weave artistic values, devoting renewed appreciation to cultural heritage around the skills of weaving carpets (zarabi) and the importance of a link to the public in order to transmit a social and educational message through art.

.

Mostafa Maftah: I’ll begin at the beginning: the architecture of the medina. I am passionate about the time inscribed in old walls, the first mirrors reflecting a society. Those walls are colored using natural pigments, ocher or iron oxide, blue, yellow; primary colors which, let us remember, will mark my entire life. I am fascinated by their material source of color, like a phenomenon of aging. As a child, I was very amused and intrigued to uncover the strata of color on the wall. I bring them to my artistic practice; my paintings have become their museum. I tirelessly repeat six coats of color, distinguished by lime, made of the same pigments used to renovate the outsides of houses. Next, I introduce the principle of water erosion in order to excavate and reveal the different coats laid down on the base. With an iron spatula or a piece of tracing paper, I move my hand over the whole canvas to find places where it’s fragile or where I can assert myself. I also give the fabric freedom, which allows me to liberate my painting. Like a photographer who goes into the darkroom to make prints, I wait for the response to erosion and what it can reveal. I work with the three-dimensional relationship of paint, including the wooden base, to expose natural aging. I can tamper, speed up the aging process, but only up to a point because that’s not how those walls aged. I always seek the influence of the environment in which I life. Like here, in my medina, I am faithful to my neighborhood. I am nothing but a mirror of society that passes through me: its medium.

Elsa Guily: At the Casablanca Academy of Fine Art, you created Feu Océan (“Ocean Fire”), presented at the In the Carpet exhibition at the IFA gallery. The work merges a diversity of creative approaches from your practice, including sculpture, painting, and weaving. What brought you to de-compartmentalize academic and traditional techniques?

MM: In Feu Océan, there’s that give and take between the carpet, the painting, and the artist. I give the materials nuances that you wouldn’t find in traditional practices. It’s a creative conversation between the traditional carpet-weaving of my childhood and what I learned from the craft revolution at the Academy of Fine Arts. I was born in a house where there was always a loom. Even when I was eating, it was normal to find a woolen thread in my mouth! I chose the weaving studio out of that familiarity with the medium. I quickly realized I had my own technique of weaving that I had learned when I was younger. So I left the conventions of the traditional technique, applying my pictorial gesture to the way I handled wool. I echoed the layering of colorful coats by multiplying multi-colored threads. Normally, a carpet is made on a white background. I reverse those conventions, starting by filling it with scraps of wool. I work with what I have on hand to liberate creative processes from all material constraints. I use a mixture of different weaving techniques: flat blanket-weaving, braiding, knotting, and so forth.

EG: Artisanal knowledge is passed down by repeating gestures. It’s like a way of evoking time and experience. As an artist, do you see yourself as a weaver of links between past and present? Are you reminding us that art is necessary to open up to the world?

MM: When you’re weaving, it’s important not to deny the past, which is there to transmit to the future. By calling upon my entire existence, the gesture becomes a universal language. In that sense, the transmission is linked to a kind of self-meditation. There’s a give and take, an exchange between myself and the subject. It’s the sequence of sensation. That is why I need to use my hands to transmit. I give the piece the artist’s experience with its sensations. I give it a soul with my touch, my time, my changes. The piece lives with me. It surrenders to my emotions, my meditations, and my states of mind.

.

.

EG: Traditionally, in the art of carpet-weaving, women work together on large looms. It’s an art form that carries collective memories and whispers, a tool of trans-cultural communication between different communities and regions of Morocco, even across the globe. Your artistic practice echoes this relational dimension now that you are working on your “woven paintings” with your wife Malika. What is the role of the collective dimension in your artmarking?

MM: As a child, I was drawn to weaving for its social dimension. I knew how to tie a knot before I could speak! My mother and grandmother worked together. Malika comes from a tribe from southern Morocco in the Todgha Gorge. That’s a region that managed to persist in passing on artisanal knowledge. Moroccan carpets change like the language and its dialects, which vary from the Atlas Mountains to the Rif. Carpets also feel those variations. Malika passes that specific regional knowledge on to me, and in return I give her my knowledge as a “contemporary” artist. The carpet gives us a common creative language like a poetics of our relationship. I’m always trying to introduce people into my artistic practice as Brecht did for theater. My work goes beyond that self-centered intimacy of the artist; it is social. My studio is always open to people. It’s a site of interaction with the public.

EG: How can your art be deployed in public space?

MM: In the eighties, I worked on the square of the old port in Marseille with a piece of fabric like a kind of wall. I called on passersby to participate and intervene. The wall itself is a mirror of society. And yet it sometimes bears the inscription, “Post No Bills.” That law places conditions on free expression in public space. As an artist, I struggle to liberate that freedom of expression. So I worked on that set of issues by crossing out the word “No” from the regulation “Post No Bills,” so it would read affirmatively: “Post Bills.” In so doing I thwarted the epistemological violence implicit in that relationship between image and text. That’s what street art is: getting art out into the streets, giving it back to everyone. Sometime soon, I’d like to do a performance piece in public space about the transmission of traditional knowledge and the challenges of creativity. Every form of weaving is its own form of writing. We need to unite around our cultural heritages with their many hybridity-imbued meanings, and share them once more to create an intergenerational discussion in a common gesture.

.

Elsa Guily is an art historian and an independent critic living in Berlin, specialized in contemporary readings of critical theory and the political challenges of representation.

.

More Editorial