Echoes of Zaire: Popular Painting from Lubumbashi, DRC - A remarkable show in London explores memory and history in the Congo. Liese Van der Watt went to take a look.

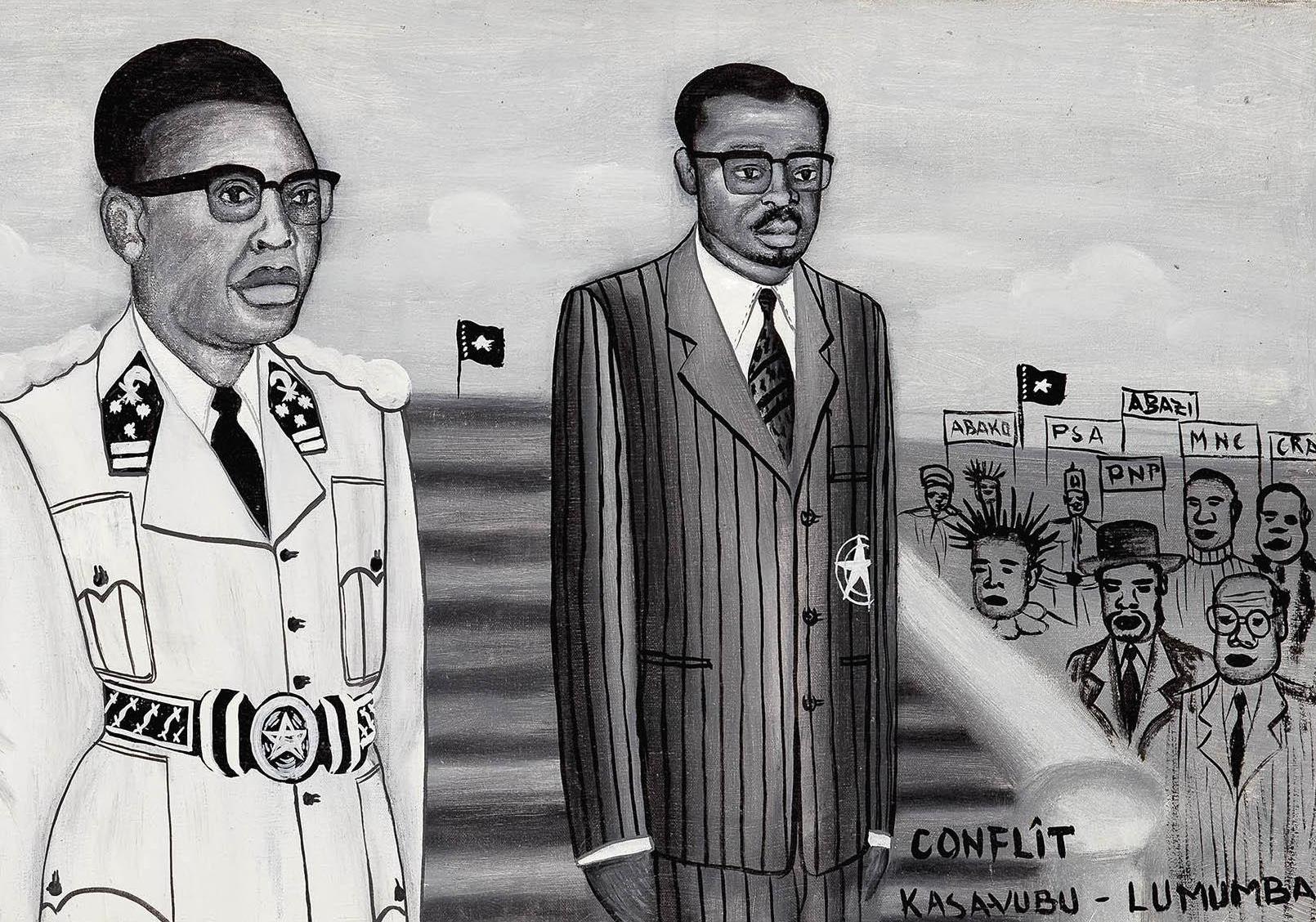

Conflit Kasavubu – Lumumba - Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu

In the 1970s, a Congolese painter named Tshibumba Kanda Matulu began to paint a history of what was then Zaire. This history, as the anthropologist Johannes Fabian pointed out when he collaborated with Kanda Matulu on a book some years later, was “not just a story, but an argument and a plea.”

History is of course never “just a story,” and the extraordinary exhibition 53 Echoes of Zaire that just opened in London, showing some of these paintings by Kanda Matulu and four other painters from the Congo, makes very clear that these painters’ version of history is indeed an emotive, impassioned plea to tell their side of the story, to insert narratives into the vacuum left by official versions of history that circulated at the time.

The exhibition was curated by Salimata Diop from the Africa Centre in London in cooperation with the Sulger-Buel Lovell gallery. It comprises 53 paintings by artists Louis Kalema, C. Mutombo, B. Ilunga, Ndaie, and Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, belonging to the Belgian collector Etienne Bol whose late father Victor Bol collected these works while spending time in Zaire in the 1970s.

The artists are all self-taught and the exhibition shows a series of works all executed in a style similar to what is sometimes called the Zaire School of Popular Painting. The most famous of this so-called school is probably Chéri Samba, who shot to fame after he was included in the Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of Earth) show at the Pompidou in 1989. These works are painted on flour sack rather than canvas, often with a limited palette of poster paints and with thick brushes. But whereas Samba and his colleagues from Kinshasa tend to record everyday events, the works on the current show are all from painters around Lubumbashi, in the south, with a focus on historical topics. This is probably as much the result of the collector’s keen eye as anything else – the catalogue tells us that these works were made for a local audience and were mostly sold to local people, so one may surmise that these artists probably also painted genre paintings for a local clientele.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue that has reproductions of all the paintings, but unfortunately does not tell us much about individual works. Granted, very little biographical information about these artists is known and none of them could be found in the lead-up to this exhibition – we don’t even know if they are still alive. Efforts to reach Kanda Matulu – by far the most proficient of the group – have been unsuccessful; his last works date to 1982–83. But the catalogue does not explain or contextualize individual images or events, and viewers are left piecing together the history for themselves. This is a shame, as these works were clearly meant to inform and educate their viewers. It would be nice, therefore, to be able to partake in this project knowing more about the incidents being memorialized and their significance in this indigenous history of the Congo.

It is quite interesting, for instance, to know that the aforementioned academic and anthropologist Johannes Fabian published a book in 1996 containing a series of a hundred history works by Tandu Matulu, entitled Remembering the Present. The two became friends in 1973 when Tandu Matulu was around 27 years old and needed a sponsor to execute his aspiration to tell the history of Zaire in a series of paintings, rather than stick to the genre paintings so popular with the local public. Fabian mentions that while he and Tandu Matulu were working on this project from 1973–74, he “found amongst my expatriate colleagues a few buyers for several shorter versions of this series.” This is probably how Bol acquired his collection.

Several works from Fabian’s book are repeated in Bol’s collection, making it clear that the artists repeated the same images, focusing on key episodes. The exhibition is organized around five themes representing Belgian colonization, the mines around Shaba (now Katanga), the independence of Zaire, post-independent moments of conflict, and the pre-colonial past. Clearly these painters are imaging a shared system of memory. The same image crops up over and over again under the heading “Congo Belge” (Belgian Congo): a white official in a white safari-style uniform overseeing a black uniformed man, whip in hand, flogging a black subject lying on the ground in front of him. Often women in traditional dress are onlookers, and in quite a few works black subjects have chains around their necks. These are images of such horrific dimensions that they are ingrained in the popular imagination; memory becomes a people’s history.

Another popular topic repeated by a few of the artists is the beheading of Msiri, the king of Katanga, by King Leopold’s army in 1891. Some official European histories published in France related that after Msiri was killed by gunfire, his head was put on a pole as a lesson for his people. Indigenous oral history relates that Msiri’s body was returned to them without a head and no one knows what happened to the head. The exact details are imprecise, but it is clear that this episode plays an important part in the popular narrative about colonial occupation and resistance.

The works of Kanda Matulu clearly stand out, so often showing a wonderful eye for detail and a gift of observation here: the uniforms of colonial officials is painted in precise painstaking detail in his “Colonie Belge 1885–1959” (also repeated in Fabian’s book), buildings reveal an architectural sense of structure, and his many portraits of Lumumba are unmistakable likenesses. The black-and-white portraits of Lumumba in particular – probably taken from newspaper photographs – are some of the most interesting in the exhibition and reveal Matulu’s keen interest in aesthetics and representation. His works are richly annotated, similar to Cheri Samba’s, so as to inform his audience unambiguously about whatever he is referring to and how these images should be interpreted. This sentiment – so foreign to the Western art world, which is probably why Chéri Samba remains so popular in the West – reveals how much these works are intended to document and memorialize, to stand testimony to a history all too willingly forgotten.

For this reason alone – and many others to do with the works’ cohesion– one hopes that the collection is sold to an institution open to the public. This is a powerful document that needs to be seen in its entirety.

Liese Van Der Watt is a South African art writer based in London.

More Editorial