A new generation of Malian photographers is tenaciously defining their own visual language, one that reflects the upheavals on the streets and in their inner lives.

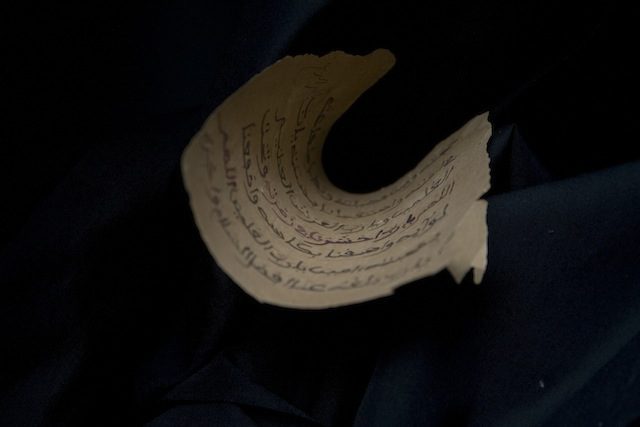

Seydou Camara, Les manuscrits de Tombouctou, 2009. Courtesy of Bamako Encounters

Mali is a landlocked country. The history of its exchanges with the rest of the world was inscribed, even before the incursion of French colonialism, on a South-North axis. This natural orientation of trade explains the relatively late arrival of photography in Malian use. After passing from Europe to the west coast of Africa in the mid-1800s (Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria), the practice of photography traveled a long distance before reaching the Sahel in French Sudan, around the time when the Borgnis-Desbordes mission came to Bamako in 1883 (1). By their own accounts, the first photographers on Malian soil were French or Levantine civilians who had arrived, along with the medium of photography, in the retinue of the first colonists. It was not until the mid-1950s that native Malians began taking photographs themselves.

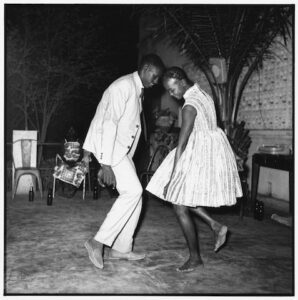

Malick Sidibé, Nuit de Noël (Happy Club), 1963 Gelatin silver print

© Malick Sidibé. Courtesy MAGNIN-A, Paris

Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé had given up photography years before André Magnin first discovered their work in 1991 (2). Sidibé had moved on to repairing and mending cameras. Keïta, retired after serving as the official photographer of the secret service, was a respected man in his neighborhood. His studio had been taken over by a nephew or apprentice. It is understandable that the first to be astonished by what happened after the meeting with Magnin – the devil according to some, or the messiah for others – were Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé themselves. Their astonishment that their archives were valued so highly by people with no family connection to the subjects portrayed was mixed with a sense of pleasure in having performed their vocation well. Keïta and Sidibé would become what Michel Onfray calls two “conceptual characters” in the elaboration of a theory of African photography.

In 1993, Françoise Huguier and Bernard Descamps, along with several Malian photographers – Keïta, Sidibé, Alioune Bâ and Racine Keïta –, began planning a photography festival (3) to get the word out to Malians themselves about the craze that had provoked the discovery of Keïta and Sidibé’s archives. While they basked in the limelight of exhibitions that cemented their recognition in Europe and worldwide, some spoke of exotic freshness and others bought negatives by the hundreds (sometimes for prices that low).

A series of exhibitions looking at pan-African photography – held in 1994, 1996, and 1998 – all drew on either collections of photography studios produced between 1950 and 1980, or the archives of national agencies of press photographs in African countries (Mali, Guinea, Senegal). Interest in Keïta and Sidibé expanded to other Malian photographers, including Abdourahmane Sakaly, Mountaga Dembélé, Adama Kouyaté, Youssouf Traoré, Félix Koné, Nabi Doumbia and Sadio Diakité. All have been celebrated by subsequent editions of Encounters, the photography biennial that has attempted to position Bamako, without the city’s consent (4), as the African capital of photography – much in the way Ouagadougou is vaunted as “the capital of cinema.” (5) By the time Encounters, created in 1994, came of age in 2001, in part thanks to extensive discussion about photography in Africa as well as other circumstances (6), the reality of photography in Mali was a far cry from the claims of the trade press and professionals. Ever since the 1980s, Malian photographic practice has been dominated by thousands of young, self-taught photographers (often based in studios but sometimes on the move) who produce photographic documentation of our weddings, our baptisms, our dances, our hysterical laughter, our holiday best, the color of the ground around our homes, and “precious things whose form is dissolving and which demand a place in the archives of our memory,” to quote Charles Baudelaire.

At such festive occasions, no one deigns to discuss those photographers or their photographs. It is important, nevertheless, to talk about them. If only to stop them from perceiving that global passion for studio portraiture as confirmation that they are on the right path, the path of prosperity and posterity. And if only to stop them from believing that it is enough to wait for time to pass, to wait for their current work to age and become “vintage”. As Maurice Rheims has said, “Eventually everything will grow old. One only needs to be patient, to wait for what is new to acquire age.”

Fortunately, there are upheavals underway on the streets and in the inner lives of Malians. Revolutions are erupting. Unique dynamics are being deviced. Liberties are hatching. Many noble intentions, a wide variety of support, and most of all Malian photographers’ desire to deserve, from now on, all the attention that they already receive, have combined to produce to a new generation that is tenaciously attending every workshop and every master class to try its hand at the craft. Some of these artists are taking wise advantage of the space for meeting and exchange offered by the Encounters, in order to understand the language of photography, that “expression of purely aesthetic research.” (7)

Such photographers as Alioune Bâ and Youssouf Sogodogo (about whom we have heard little for some time); Amadou “At” Traoré and Racine Keïta (who have been forgotten); or Mamadou Konaté (still around) are the forerunners of a new generation, which appears to have enough passion and curiosity to be encouraged to dig more deeply and take more liberties. Harandane Dicko, Seydou Camara, Fatoumata Diabaté, Amadou Keïta, Bintou Binette, Mohamed Camara, and some others, without rejecting the aesthetic established by the social photography at the studios of the fifties, are surpassing the first group. They are using photography as their locus of artistic expression rather than seeing it as a magical practice that saves from oblivion the elegance of a festive occasion or the heady atmosphere of a successful surprise party. They are endeavoring to use photography as a way to take action: for their own lives and those of society at large. Their work attacks the prematurely established structures that restrict photography in Africa to the confines of a lapsed aesthetic: 1950s studio portraiture. They draw their aesthetic material from the details of their daily rebellion against the breakdown of community life. They glean from their day-to-day social experience, which saps off their future dreams without regard for their youth.

Chab Touré is Professor of aesthetics, art critic, and director of the galleries Carpe Diem (in Ségou) and AD (in Bamako).

Footnotes

(1) Erika Nimis, as quoted by Dagara Dakin on African photography, in L’Afrique en regards : Une bréve histoire de la photographie, Filigranes Editions, November 2005

(2) André Magnin recalls having discovered at a New York exhibition of African contemporary art in 1991 two photographs from the 1950s attributed to an anonymous Bamako photographer. That same year, he left to Bamako, convinced that there could not have been droves of anonymous photographers in Bamako in the fifties. Sure enough, he found Malick with the help of the first taxidriver he asked. Malick in turn led him to Seydou Keïta.

(3) The festival, titled Encounters with Bamako’s African Photography (Rencontres de la photographie africaine de Bamako), was held in November 1994.

(4) To this day the photography festival has very scant involvement from Malian laypeople and politicians alike.

(5) This was the festival’s declared objective according to the founding mission statement of Encounters with Bamako’s African Photography.

(6) The scarcity of salaried jobs has led young graduates aspiring to be photographers to work freelance.

(7) Dagara Dakin, op. cit.

More Editorial