The pioneering modernist painter and writer died in April. Sean O'Toole recalls his early years as a prize-winning writer and pen pal of Langston Hughes

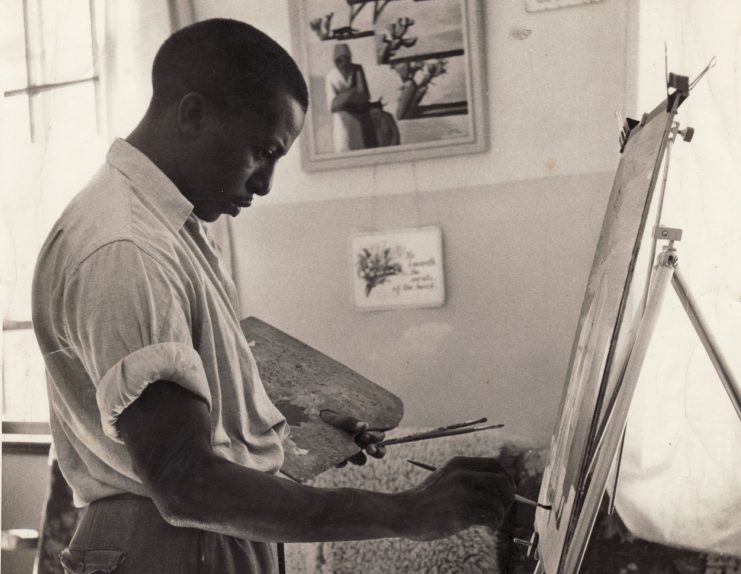

Peter Clarke painting with Woman with goats 1961

Every artist has a point of origin: for Peter Clarke, the octogenarian painter, printmaker and man of letters who passed away in his sleep on 13 April, it was Corporation Street. Located on the edge of District Six, a mixed-race settlement largely bulldozed into oblivion by apartheid planners after it was declared a whites-only settlement in 1966, Corporation Street is an odd little side-street, inauspicious and mostly forgettable.

Beginning at Darling Street and ending outside the Department of Home Affairs on Barrack Street – a place familiar to all migrants living in Cape Town – the street spans a mere four city blocks. Pin straight and partially tree-lined, key landmarks include a bunker-like building filled with police detectives, the corporate head office of retailer Woolworths, a hotel, as well as a doorway used by parolees and probationers reporting to the Department of Correctional Services.

In January 2013, during the run of his career retrospective, Peter Clarke: Wind Blowing on the Cape Flats at Iniva, Clarke told a London audience about his first exhibition at 14 Corporation Chambers, Corporation Street. It took place in 1957 – a year after Clarke resigned his job as a store assistant at a military dockyard to spend time working as an artist. “I had wanted to have a one-man show for a long time,” Clarke told Hans-Ulrich Obrist during his public conversation at Rivington Place.

.

.

Commercial dealers did not share Clarke’s enthusiasm for a public showing. “Your work is not of the required standard,” he was told. In the manner of countless artists before him, Clarke, an impish personality with a worldly understanding of art, grumbled about his lack of prospects to a friend, James Matthews. Well-known for his later poetry, urgent writings speaking of imprisonment (both literal and figurative), Matthews responded with a novel idea. Employed as a journalist at the Cape Town offices Golden City Post, a tabloid newspaper aimed at black readers and owned by Drum magazine publisher Jim Bailey, Matthews suggested Clarke put up his work at the newspaper’s office on Corporation Street.

“I thought that was rather unusual but we organised it, had the show, and people came,” recalled Clarke. “There were reports in the newspaper, people came again and again after that, and it was a wonderful experience – in fact, it was the start of my career as an artist.” Clarke was amazed that the building in which he had exhibited in was still standing. He told Obrist that he hoped they (he didn’t specify exactly who) would install a plaque outside the building saying: “This is where Peter Clarke’s action started.”

It is a tip-top idea. Trick is, I am not sure exactly where 14 Corporation Chambers is on Corporation Street. And Clarke – who lived the Duchampian life of a bachelor in Ocean View, a weather-beaten residential enclave overlooking Wildevoelvlei, a wetland south of Cape Town – is no longer a telephone call away. It is time for biographers to step in.

Fat chance. Amongst the various genres open to art writers, biography always places poorly. In South Africa, where a robust indigenous publishing culture flourishes, biographies focussing on singular artists remain infrequent. David Goldblatt, Peter Magubane and Jürgen Schadeberg, all prominent photographers nearing the end of their productive lives, are without biography. Ditto painters Durant Sihlali and Ernest Mancoba, both dead. Comparatively speaking, Gerard Sekoto has been luckier, N Chabani Manganyi, a former clinical psychologist, writing two biographies of the South African modernist painter whose career successes motivated Clarke to pursue his own ambitions.

.

Peter Clarke ‘Listening to distant thunder’ 1970. Oil and sand on board , 610 x 764 mm. Collection, JohannesburgArtGallery

.

In a 2008 interview, Manganyi elaborated the function of biography. “I do not consider biography primarily as a narrative preoccupation with individuals as individuals,” he said. “A delicate and very important balance needs to be arrived at. Thus, the Sekoto biography begins with a flashback to the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth in the then Eastern Transvaal; the far reaching social, political, cultural and religious changes which determined the kind of family Sekoto was born into, the evangelical zeal at Botshabelo and the schools he and his brother attended. There was a whole dynamic at work. This context was at the heart of the approach I adopted, the harnessing of what C Wright Mills described as ‘the sociological imagination’.”

For any enterprising Clarke biographer (where are you?), Corporation Street represents an important moment, crucial in fact. Clarke’s entire career radiates out from this point. I am only slightly exaggerating. In 1955, then still living with his parents in Simon’s Town, the military harbour southeast of Cape Town, Clarke – he was racially classified Coloured (of mixed-race ancestry) – won the first prize in a short story competition organised by Drum.

Amongst the notes of congratulation, he received a letter from American poet Langston Hughes. Clarke, a prolific letter-writer throughout his life – he even corresponded with young painter Mawande Ka Zenzile, currently presenting new work at Stevenson – responded with a letter. It included a gift of six paintings and some poems. “They’re very pretty,” wrote Hughes of the poems, “but I don’t think nearly as good as your short stories or your painting, so maybe there’s no harm done if you don’t go back to poetry.” Clarke accepted the advice warmly.

In a follow-up letter, written over successive days in early March 1955, Clarke reveals many things. Books of a certain type were hard to come by in the white-controlled state: Clarke asks after a copy of The Ways of White Folks, a collection of short stories by Hughes. An art lover as much as a maker, Clarke recounts visiting an exhibition of early twentieth century German graphic art at Cape Town’s National Gallery, which decades later, in 2011, hosted a retrospective of his work, Listening to Distant Thunder: The Art of Peter Clarke. “Contemporary German art is vigorous and stimulating,” writes Clarke.

But it is the prickly social relations hinted at in his letter that really fascinate. They offer a vivid sense of the literary and cultural scene in Cape Town, one in which there is barely enough elbow room, a fact that persists to this day. On author Richard Rive, who he beat in the Drum short story competition, Clarke writes: “I’ve seen him around Cape Town but we aren’t friends even though we know each other.”

Rive, who later received acclaim for his 1963 short story ‘The Bench’, was less diplomatic about Clarke in a 1955 letter to Hughes. “We were together in the same Boy Scout troop, 2nd Cape Town, where I was a King’s Scout and he was a Rover,” notes Rive as a way of subtly inferring who’s who in the cultural hierarchy of Cape Town. Of Simon’s Town – where Clarke lived with his parents until they were forced by apartheid planners to relocate to Ocean View – Rive is equally dismissive. It is more British than Plymouth, he quips. “I am sure Peter reads Kipling in the privacy of his room.”

.

.

I didn’t see any of Kipling – no Jungle Book, nor Puck of Pook’s Hill – when I visited Clarke at his terrace home in 2011. Amongst the horizontal piles of books stacked near his front window, a book about Hiroshige, another about Italy’s Arte Povera movement, as well as The Artist in the Garden, Angela Read Lloyd’s 2009 biography of Moses Tladi, the first black artist ever to exhibit in the National Gallery. These books, which included others on Aztec and Folk Art, operate like a Tom Culberg painting, in which book collections operate as ersatz portraits of their owners. Amongst the things Clarke spoke about the day I visited was a 61 x 77cm oil on board painting titled ‘Listening to Distant Thunder’. The work depicts four figures, a mother with her three children, standing next to a bare tree. Clarke painted this extraordinary flame-coloured painting in 1970. Variously known as ‘Abandoned Family’ and ‘Wood Drifters’, the work echoes a barren, windswept scene Clarke drew in 1961. Like many of Clarke’s works, whether executed in oil, watercolour, gouache or pencil, ‘Listening to Distant Thunder’ underscores his abiding commitment to the human form, his singular, stout figures recalling, in volume at least, Picasso’s neo-classical portraits from the early 1920s.

“There are so many things about people that I find endlessly fascinating,” he told me, echoing something he wrote to Hughes in 1955. “I prefer pictures which include figures. Landscapes are nice but I feel anybody can do that, but with figures there is always something that can be told.” Clarke was a formidable figure, an artist who straddled a landscape steeped in failure and retrieved from oblivion. His life story deserves a richer telling than the few obituaries and long-form interviews that have come to summarise his life.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and co-editor of CityScapes, a critical journal for urban enquiry. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

.

Remembering Peter Clarke

South African National Gallery, Cape Town, on Saturday 28th June, at 2pm

Peter E Clarke, the internationally acclaimed and respected Cape Town artist, died at the age of 84, on 13th April 2014.

“Remembering Peter Clarke” will be held at the South African National Gallery, Cape Town, on Saturday 28th June, at 2pm. Guest speakers, musicians, poets and artists, will gather with Peter’s family, friends and admirers, to pay tribute to the life and work of this remarkable man. The event is open to anyone who would like to attend. The organisers are grateful to the South African National Gallery for providing a venue for this event, which will take place in the midst of the current exhibition of photographs by Peter’s long-time friend, George Hallett. Enquiries may be directed to david.worth@uct.ac.za

More Editorial