CAM, Raleigh, United States

03 Mar 2016 - 19 Jun 2016

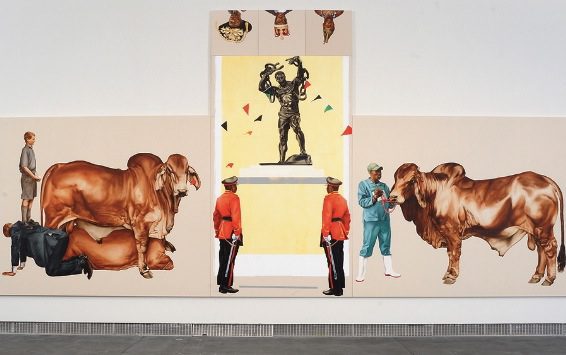

Terra Pericolosa, 2013; courtesy: artist

The exhibition’s title evokes the idea that people are often more comfortable accepting or believing what is told to them by those in power, rather than challenging and investigating the authenticity of information presented as historical fact. Interweaving their personal experiences and memories into broader historical contexts, these artists create work that is in strident opposition of passive acceptance.

With ruby onyinyechi amanze (b. 1982, Nigeria), Duhirwe Rushemeza (b. 1977, Rwanda), Sherin Guirguis (b. 1974, Egypt), and Meleko Mokgosi (b. 1981, Botswana).

The artists’ cultural backgrounds, as well as geographic diversity, create an opportunity for a provocative examination of varied perspectives of the truth. Although these artists are from four different African countries their work addresses universal issues that are relevant across all borders.

ruby onyinyechi amanze’s drawings envision speculative narratives of self-discovery, supernatural existence and spatio-temporal escapism to evoke ideas around cultural hybridity, belonging and displacement. Her works on paper are influenced by textile design, photography, printmaking and architecture.1

Currently residing in the US, amanze is of Nigerian birth and British upbringing. Not easily categorized, in her formative years amanze sought to determine her own definition of personal identity. amanze’s fantastical drawings include an ever-growing cast of characters including Audre the Leopard, Pidgen, and ada the Alien – often described as the artist’s alter ego. These characters and others were envisioned during amanze’s travel to Nigeria as a Fulbright fellow in 2012.

amanze’s drawing, kindred (2014) presents her characters in a family portrait that is both stately and playful. Other works such as ada rests in places unknown (2014) and tenderhearted (audre) crosses the sea (2014) place amanze’s cast in various otherworldly interactions that volley between the familiar and pure fantasy. amanze has stated that « ada the Alien was born out of necessity: the need to identify a neutral voice through which to tell stories that highlight the complexities of experiencing home as an alien or foreign being. »

Sherin Guirguis

Born in Luxor, Egypt, Sherin Guirguis’ identity was developed in a rapidly changing cultural environment that included her family moving to the US when she was 14 years old. Guirguis originally studied geology, but would later commit herself to being an artist.

Influenced by Middle Eastern architecture and West Coast Modernism, Sherin Guirguis’ Untitled (Bab Huda), 2013, Untitled (lahzet zaman), 2013, and Untitled (Bab El-Hadeed), 2013, explore transitional spaces from historically relevant locations in Egyptian feminism, more specifically the life of Huda Shaarawi, a pioneer Egyptian feminist leader and nationalist, and the birth of the Egyptian Women’s Union. By continuing her previous practice of hand cut works on paper, embedded with gold powder and gold leafing, Sherin uses architectural references such as doorways, windows, and arches to convey the significance of the site and the role it plays in establishing a radical ideology. The paintings include a representation of the door to Huda Shaarawi’s house (one of the last functional harems in the country) and the Cairo railway station Bab El-Hadid, where she and her colleague Saiza Nabrawi removed their veils.2

Meleko Mokgosi is concerned with the history of painting. However, through his work he critiques and subverts it. Mokgosi’sRuse of Disavowal (2013) is part of Pax Kaffraria (2010 – 2014) the artist’s eight-chapter project that takes Botswana, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe as case studies.

Pax Kaffraria brings together two terms. « Pax,” taken from the original phrase: “we Romans have purchased the pax Romana with our blood,” highlights the essence of institutionalized, enforced “peace” at the height of the Roman Empire. “Pax Romana,” contrary to conventional belief is not about peace but rather about nationalism; it is precisely about the bond between blood and soil that undergirds nationalist projects and a certain understanding of “peace.” “Kaffraria” is a term that was first used by the British in the eighteenth century to establish “British Kaffraria:” a subordinate administrative entity that was primarily inhabited by the Xhosa. More precisely, “kaffraria” is a British adaptation of the word “kaffir,” derived from Arabic and coopted by the Dutch or Boer in South Africa, and used as the equivalent of the derogatory term “nigger.” Pax Kaffraria then is a forcefully made appellation that is chiefly historical and mythical, thus the project primarily aims to investigate the multiple facets that account for the driving force of national identification and liberation movements both in their emergent and subsequent forms.3 At its core, the Pax Kaffraria series considers the creation of capital “H” History and the ways in which societies produce narratives. The imagery is drawn from the histories of Southern Africa, transmogrified under artist’s brush as questions of nationhood, colonialism, history and post-colonial aesthetics.4

Duhirwe Rushemeza’s current body of work evolved from earlier practice developed in response to the 1994 Rwandan genocide where 800,000 men, women, and children perished. Using reductive Linocuts – a printmaking technique – Rushemeza created images of young survivors. The artist subsequently found inspiration from other aspects of Rwandan history, as well as her travels to Cote d’Ivoire in West Africa, and Germany. Inspired by traditional imigongo cow dung paintings, Modernism, and childhood memories of deteriorated colonial buildings in Rwanda and other African countries, Rushemeza’s sculptural paintings Who Am I When I Am Free (2014) and Red Ochre, White and Blue (2014) appear to have been extracted directly from the walls aging buildings. However, they are masterfully constructed in the artist’s studio through a process that includes building up dozens of layers of paint and metal detritus, and then stripping away those layers to mimic the effects of weather, erosion, and the passage of time.