Varoius Family Homes, Bamako, Mali

30 Nov 2019 - 31 Jan 2020

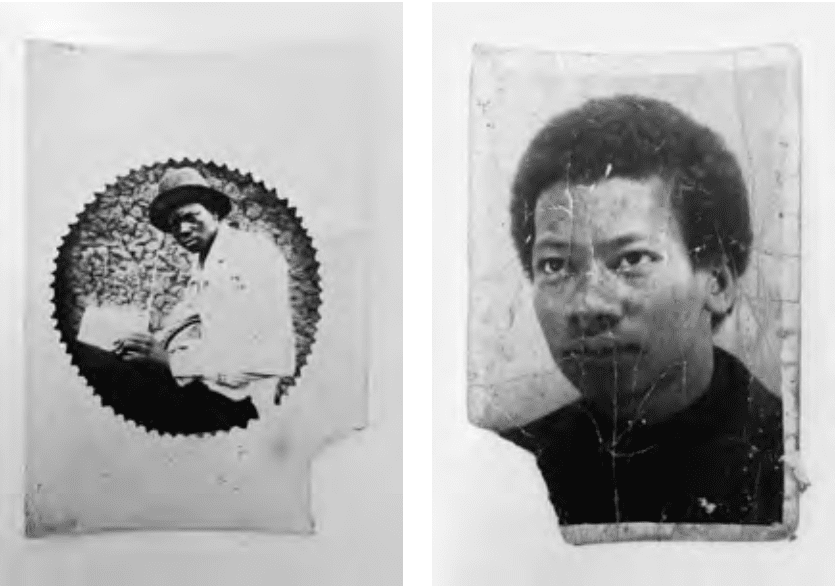

Archives of Family Cissé.

It has often been said that Bamako is the city of photography. This is evidently so, not only because Bamako’s history of photography is as old as the history of photography itself, and not only because for the past 25 years Bamako has been the host of Africa’s biggest festival of photography, but also because Bamako, as a physical and spiritual space, is the bearer of a particular light.

A light that calls for one to want to draw with it. That light is thematized and negotiated in Souleymane Cissé’s legendary 1987 film Yeelen, which in Bambara means “brightness” or “light.” A concrete light as well as a light of precognition. No doubt the city has produced or been host to photographers of the calibre of Malick Sidibe, Seydou Keita, Abdourahmane Sakaly, Mamadou Cissé, Adama Kouyaté, Tijani Sitou and many others.

Though many of these photographers are highly celebrated artists today, and their works exhibited in museums, galleries, and collections all over the world, most, if not all, of their works were produced for what one might choose to call the “familiar and familial” consumption. As portraitists they produced images of peoples of different classes and walks of life in their

studios or outside—in hotels, as well as in peoples homes or restaurants and other popular cites. Others made photographs

for official documents for the police or insurance companies, but in most of the cases these photographs ended up in family

photo albums, or framed on walls in living or bedrooms in family houses. These images told stories of friendships, relations,

status, a becoming nation, style, an African consciousness, music, womanhood, and dignity.

While we have all pilgrimed to big museum institutions around the world to see retrospectives of the likes of Sidibé or Keita, people in Bamako see their works regularly in family albums or hung on walls. It is not unlikely to enter someone’s living room and be introduced to an image of the parents, aunties and uncles, or some other relatives taken by the aforementioned photographers or some other great portraitist whose light hasn’t yet shone in the art or museum world.

For this 12th edition of the Bamako Encounters we would like to acknowledge that while it is important to present and see photography in musial spaces, most photographs of the legends Bamako were made for the “familiar and familial” and are worth seeing them in such spaces. Seeing them in situ. In their natural habitats, so to say. There is a yawning gab between seeing the portrait of a nameless woman holding a flower in a museum, to the portrait of Fatoumata holding a flower in a framed image in the living room of her nephew. In the former, the subjects are stripped of their identities and become objects of a musial gaze, while in the latter they are situated within this “familiar and familial” spaces. These spaces of the “familiar and familial” are also exhibition spaces, per se. While in some spaces the photographs are presented with diligence and rigour, and in others less cared for, they all still tell stories of their time as set in relation and situated within certain sociocultural and sociopolitical realities.

For this 12th edition of the Bamako Encounters we have invited five families to open their doors to our visitors and present photography in situ. Once every week, these families will welcome visitors of the Bamako Encounters into their homes and present a regular “exhibition” of photographic works beyond the studio and beyond the gallery, but in the spaces they were meant to occupy.

Of the five families that have offered to be part of this special project, it is worth highlighting the family home of Django Cissé, himself a legendary photographer, especially known for his iconic post card photographs of import- ant architectural, cultural, political and historical sites and events not only in Mali (especially Bamako, Djenné, Timbuktu, and the Dogon country), but West Africa at large. In the family home of Django Cissé—who studied drawing at the National Institute of Arts in Bamako, before becoming a teacher at Badalabougou High School in Bamako, where he bought his first camera from a student in need of money, and later taught himself photography—very few portraits can be seen on the walls due to his religious inclination of non-representation, but enlarged landscape photographs are seen on the walls, as much as albums of hundreds of his photographs and postcards that are part and parcel of the inventory of the familiar and “familial.”