Afikaris, Paris, France

10 Jul 2021 - 14 Aug 2021

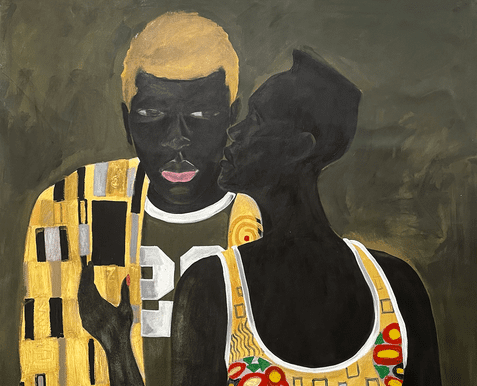

John Madu, The Kiss (Detail), 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 121 x 121 cm. Courtesy the artist

Regardless of time or geography, uprisings around the world have always been a testimony to a certain contestation of power, a break from the established order, a need for change, in harmony with the evolution of mentalities and society itself. In parallel, art carries the voice of these movements in their multiplicity.

Through the eyes of Nigerian artist John Madu and Senegalese painter Ousmane Niang, the exhibition Figures of Power brings together and confronts two very different pictorial languages, to ultimately suggest several readings of power. Both artists use their art as a weapon. They both appropriate history and take a stand. While Ousmane Niang examines the relationship between the dominant and the dominated, he does not remain a spectator and suggests solutions to the rampant societal issues. Similarly, John Madu overturns traditional clichés of domination and launches a debate on identity, in a context of globalisation. He moves away from stereotypes of gender, class, and origin, to better deconstruct them. In this way, each colours their work with their own definition of call for action and power.

Ousmane Niang’s art itself embodies these figures of power. Through the marked distinction between the anthropomorphic animals and the wild, as well as domesticated animals he depicts in his paintings, he illustrates questions of domination and hierarchy. He explains: « the animals that are humanised: they are the dominant ones. They are an embodiment of power. The animals that remain animals are the ones being dominated. »

There is a visual separation between the strong and the weak, between those who do the action, those who undergo it and those who are confronted by it but do not respond to it. From one painting to the next, the one who was once weak and powerless, finds himself in a position of strength. On the canvas, a role-playing game, as well as a game of influence takes place, illustrating a power struggle.

It is therefore quite natural that Ousmane Niang has been interested since 2019, in the pictorial treatment of games in art. He then discovered Barthélémy Toguo’s proposal on paper, entitled What’s your name? which was produced between 2004 and 2005. Ousmane Niang departed from it and created the Jeu de cartes series. Here, the traditionally royal figures are replaced by animals. He explains « I wanted to detach myself from the traditional playing card motif. From there came this reinterpretation of its composition. Thus, in my works, the characters are extracted from the card in the background. My approach is political and evokes games of power. »

On one card, the bird and the cat stand and share a fish, on a table strewn with feathers. On another, a fish and a bird are combined with the same body. Their heads are draped in the cloak originally worn by the King. A fish and an eagle replace the sword where a fishbone and a feather replace the colour of the card. Ousmane Niang plays with the codes of the game and revisits them. Although he reverses the roles, he does not choose the protagonists of his fables by chance. They are used for what they symbolise and for the meaning that the artist projects onto them. While spiritually the bird embodies our highest aspirations, for Ousmane Niang birds are the freest animal because of their ability to fly, swim and walk. It is in itself, a symbol of power.

In addition to the striking animal figures in Ousmane Niang’s work, the dots that inhabit and adorn his paintings are also characteristic of his art. The dot is central. It does not create the motif, it completes it. It provides colour and depth. Beyond giving a particular aesthetic to these humanised animals, it carries, above all, meaning. If each point is double for Ousmane Niang, each problem comes with its solution. The artist suggests avenues for reflection. It is a call to remain on the lookout, to concentrate on a situation to solve it. His paintings are not meant to be only contemplated. They are a call to action, inspiring a sense of power in oneself, like an echo of the uprising of the Senegalese youth in March 2021.

Through his paintings, John Madu empowers his characters. He frees them from any pre-constructed social norms and rewrites a world where everyone is free to be whoever they want. His visual universe is marked by numerous references. His works are as many nods to the history of art as to Nigerian youth and pop culture. In these everyday scenes, Vincent Van Gogh, Gustav Klimt and Keith Haring are never far away. They hide behind a door, or on a pair of shorts. Sometimes they even permeate the entire artwork with their characteristic features. This mixture of influences reflects the artist’s personal experiences and his vision of the world. He underlines « my work is universal. I think inspiration is universal as well. So, my art can’t refer to only a new type of Africa or new trends from Africa. Art is not stereotypical. I’m not influenced by indigenous factors. My art is influenced by universal factors, because I feel the world has become a small place and we are affected by what affects other parts of the world. »

While he paints his friends or reinvents classic paintings, John Madu seeks above all to record history. This history is his own. It is the story of the young Nigerian generation, lulled by a globalised and universal culture. He analyses this confrontation between individuality and uniformity. In his paintings, he distorts reality to correspond to the way he sees reality. He questions the construction and affirmation of identity. He blurs the border between feminine and masculine. He plays with the curves of the bodies and the short hair of his models.

A song for Maness is a portrait of a woman from his entourage, whom he represents on canvas using the features of a man. He questions the very notion of gender. He deconstructs it. He underlines its limits and denounces its stereotypes. He echoes the words of Nigerian writer Chiwanda Ngozie Adichie, who deplores the notion of gender, seen as a way to prescribe how everyone should be, rather than recognising how everyone is. With his brushes, John Madu shows a fluid identity that begs to be released. He captures the singer’s lascivious pose, his attitude, his evasive gaze. He plays with the pink tones of the wall in the background to create a contrast with his skin. If the composition of his paintings is photographic, one can think of the series Fine Boy No Pimple (2017) by Nigerian photographer Ruth Ossai. Through these pictures, she also seeks to question concepts of gender, masculinity and being a man in Nigeria. She deplores a society in which gender roles remain largely predefined and intends to create a dialogue around identity. John Madu extends this reflection by diverting Gustav Klimt’s famous Kiss (1908-1909). By reversing the original roles – it is now the woman who kisses the man – he pleads for women’s empowerment in a traditionally patriarchal Nigerian society. In the same vein, Bromance in battle denounces gender stereotypes and behaviours that claim to answer the question of masculinity. Although the scene takes place in the ring, the two men are not fighting. They are embracing. John Madu ironically draws inspiration from boxing matches and offers a tender scene between two men, breaking with tradition.

In this way, John Madu, by diverting both masterpieces of modern art and scenes from everyday life, reverses the roles and turns his models into figures of power. Through the symbolism of games, anthropomorphism, and the pointillist technique, Ousmane Niang represents the struggle for power and the resulting power struggle. Both are committed artists who infuse their art with an educational virtue. Ousmane Niang claims: “I want to initiate the youngsters at research and creation to prevent them from being only consumers.” In the end, isn’t art itself a form of power?