Montague Contemporary, New York, United States

18 Nov 2021 - 08 Jan 2022

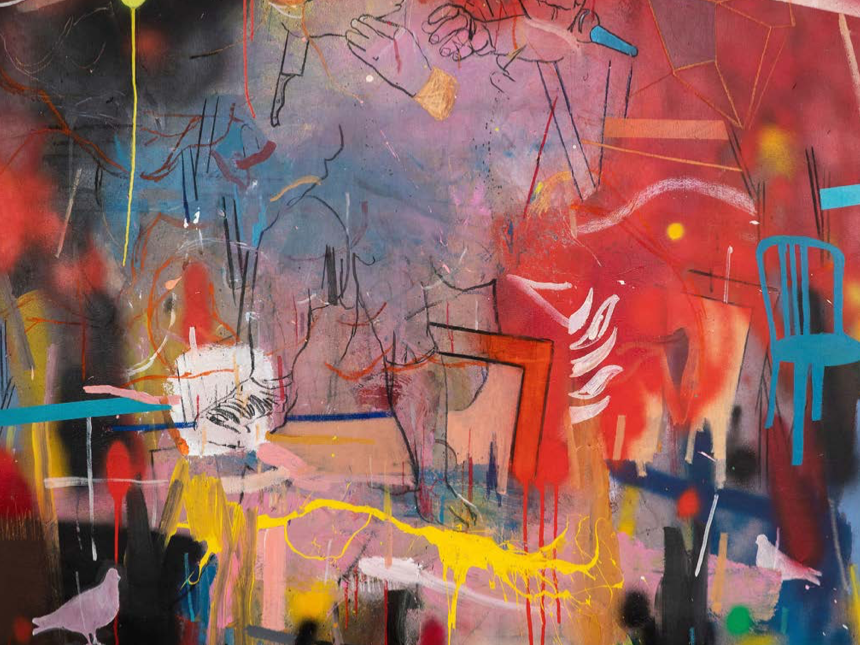

Thameur Mejri, UNTITLED (ON/OFF), Detail, 2019. Mixed Media on Canvas 160 x 140 cm

Montague Contemporary presents Folds in the Soul, a solo exhibition of works by Tunisian-based artist Thameur Mejri, curated by Khadija Hamdi-Soussi. The exhibition will open on Thursday, November 18th, 2021 and will be on view through January 8th, 2022.

Is it by chance or a simple architectural error that prompts us to bend our legs and curve our spines slightly to enter Thameur Mejri’s studio, this cubic-shaped space almost made to encompass us? I had the feeling of getting lost in a large canvas before finding myself facing him and oscillating between the artist and his work.

Looking at his painting, while listening to his words on art, politics and philosophy that he handles so well, made me draw a parallel with Wim Wenders’ film “The Wings of Desire” ( les Ailes du désir).

I could see Thameur playing the role of one of the angels Damiel or Cassiel, to reveal some of the secrets of the transcended images in front of my eyes. The oscillation between the works and the artist, led me consistently to the same iconic movie that went from black and white (the numb world) to color (desire) and thus, drove my curiosity to reach the infinite.

This meeting made me discover an artist who moves, reflects, hopes, despairs and questions, like Wim Wenders who tries to find his bearings in his native country, Berlin before the fall of the wall, from which the scars of war have not yet been completely healed. Not to let the scars heal is to keep a door ajar to the past! Does Thameur’s desire consist precisely in striving to know the past, which he considers valuable to look forward to the future peacefully?

I took the benefit of a moment of silence to venture into the observation of Thameur’s painting and to fill my eyes with this flow of images which made me take the contemplative step of listening to the pictorial shapes in order to understand things.

I still see myself immersed in the stimulating reading of the text that Deena Weinstein produced on Thameur and his painting, and I find myself regularly challenged by the idea of the fold that she detected through the geometric forms of the artist’s works.

I therefore thought of it as a game, going through the drawings and other paintings to find “the thousand folds of clothing that tend to unite their respective carriers ”

The impromptu intrusion into the painter’s cube-shaped cave, made me realize, as a revelation, that I was surrounded by receptacles, whether they were folds, envelopes, boxes or sealed vases adorning the works and participating in their composition.

If I happened not to notice their presence on certain canvases, it is not because they were not there but because they evade the undiscerning eye. In reality, they are present, lurking in the shadows and between the secure yet intriguing folds of geometric shapes.

It seemed to me, suddenly, that I was dealing, not only with a pictorial endeavor, but with a fossil ground stirred up by an aesthetic archaeologist in order to unearth some new knowledge about the history of humanity.

The receptacles remain sealed and the artist hardly tries to open them, leaving this task to the spectator who must shed his passivity and engage in the works and their cavities as in himself.

It is an invitation to a psychoanalysis of the works that stimulates the unconscious and invites it, in spite of its will, to explore various horizons and to take different directions. The folds are, ultimately, those of the spirit transcending the darkness and reaching the timeless dimension of the poetic imagination and metaphysics.

How to let go of these folds? How to proceed to something else when one is captivated by these interlocking patterns that shape the work and then un-shape it?

It is at this moment that the thousand folds of clothing, dear to Deleuze, came to mind and seemed to me as a visual and perceptive evidence. In fact, the multiplicity of images that vary in all possible ways in chaos organized by the artist, take the form of an overloaded baroque costume with its folds composed of images that escape from the cubes, here and there, containing infinite meanings, questions and answers.

And what about the human body? It is dismantled and deconstructed, the pieces of legs, hands, skulls and anatomy form a string of recognizable human forms, almost tortured, like Francis Bacon. Yet the anger still seems latent, the artist being careful not to exhume it entirely, preferring to keep it under control and to soften it gracefully by means of flat tints of colors carefully chosen and diligently applied as a representation of rationality and of a mastered anger.

Digging in this pile of forms, in this magma of colors and in these interlaced volumes, is like participating in an ancient archeology site, equipped with a trowel and a lot of patience.

One never knows what will be revealed, the eye seems to be caught by a thousand details at the same time. As one advances in the diggings and clears the multiple layers of history, the mystery grows, a Prévért-like list is established: here is a light bulb, there a knife, elsewhere an airplane substratum, even if the keystone and a link in the meaning equation remains missing.

One feels the pleasure of an artist who enjoys extending the mystery of things and immersing the spectator in infinite questioning in the way of Sappho Mitilene’s poems that disappeared forever, inviting us to imagine the evanescent and fragmented beauty. The scarcity creates the desire, stimulates and enhances the Beautiful.

Following Gilles Deleuze and his conference on the fold, Leibnitz and the Baroque […], I could not help but decompose Thameur’s painting into two distinct labyrinthine levels: the labyrinth at the bottom, the enclosed and intriguing folds, and the labyrinth at the top, the entanglements of images. I acquire the certainty that the exhibition can only be instigated by wandering through the labyrinths of these two pervasive and yet separate labyrinths, with no thread to guide us towards the exit and save us from decay.

Lastly, by revealing his childhood notebooks, preciously kept by his mother and from which he cuts out images to insert them into his painting, Thameur Mejri unveils the intimate in him and bravely defies his natural humbleness to bring me back to the limbo of his own history. It reminded me of the childhood poems of Peter Handke accompanying the film “Wings of Desire”, as to calm the turmoil of Berlin.

It seemed to me that in both of them, referring to childhood was necessary to illustrate innocence. It is not much of a retrograde but more likely a return to the future to conjure up the fate of this disillusioned humanity disenchanted by its dull existence.

Thameur knew how to embroider with the past and weave with his childhood, oscillating between maturity and innocence, while playing on the conventions of painting and philosophy. He is one of the few painters of his generation that managed to play with the intellectual and the pictorial without falling into the demagogy or the excessive stylization, he was able to translate the tumult of his native country, Tunisia while creating an art that reaches the universal.

Text By Khadija Hamdi-Soussi (curator/art advisor)

Translation by Salma Kossemtini (curator)