Ibrahim Mahama

Ibrahim Mahama

Just before the doors of Kunsthalle Bern open up after a year of experimenting with the operational aspects of institutional life, Kunsthalle Bern will wrap itself in a literal and theoretical chrysalis. The word chrysalis was chosen for its transformative connotations; the definitive moment before an insect metamorphoses. It echoes the transformative journey of an institution that heads towards new directions, having for ten months been in a fermenting process, undergoing a re-configuration of all operations, from exhibitions and public programs to all administrative aspects of instituting contemporary art. This is a pivotal moment also of physical change, given the building has been renovated for the first time since 1918 with the addition of a new entry/exit at the back of the institution; the very event that prompted to this fermentation period and gave the space to reflect on the legacy of the Kunsthalle itself.

Kunsthalle Bern is pleased to present the first Swiss solo exhibition of the artist Ibrahim Mahama, born in Ghana in 1987. The public project responds to Christo & Jeanne- Claude’s wrapping of the Kunsthalle – the first building they ever wrapped – on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 1968. The proposal interrogates the imprint of the Kunsthalle Bern on national memory, and the impact it has had to the city’s architectural and artistic landscape. It is also a critical comment on the Eurocentric focus of the Kunsthalle highlighting the role of Kunsthalle Bern in shaping the western contemporary art canon.

Mahama is known for large-scale installations and interventions, as well as for his use of found objects and repurposed materials. One recurring material in his work is the jute sack, which he collects and assembles collaboratively. He began thinking about jute sacks in 2011 while waiting at the Ghanaian border watching trucks speeding by, transporting food and other produce in these jute sacks, he thought: why is it easier for goods to travel across borders than for humans?

Through this public sculpture for Kunsthalle Bern, Mahama poses questions that discuss the current labor conditions and their ecological manifestations in the global cocoa trade but further addresses the colonial footprint of Swiss mercantile relationships to Ghana through the export of cocoa beans, the prime material for Swiss chocolatiers for hundreds of years. The plant itself was introduced in Ghana in 1857 by the Basel Mission.

Produced in Southeast Asia, the jute sacks that carry cocoa, are imported into Ghana by the Ghanaian cocoa authority (Cocobod) responsible for the transportation of cocoa beans. The cocoa traders cut open the sacks and empty the contents into containers, which then travel on to Europe. The jute sacks are then re-sold to local rice and maize traders who write their names on the sacks. This is when the material begins to live for Mahama, becoming an extension of the worker’s and trader’s bodies. Eventually, the sacks will be used to transport charcoal: their last life, since they cannot then be used for anything else. However, jute sacks are also faced with issues like insect infestation, which sometimes means they can only be used once. Especially for cocoa, significant pest infestation challenges can severely impact its quality and market value. Post-harvest financial loss can reach 30-40% due to pests such as the almond moth (Cadra cautella), Cocoa weevil (Araecerus fasciculatus), and warehouse beetle (Trogoderma variabile) a.o. These infestations can occur both in the country of production and during transportation or storage abroad. This aspect of the history of jute sacks, also allows us to imagine insects as agents of slowing down over-production, consumerism and carbon footprint, and reflects on the extensive use of pesticides since the beginning of globalization in the late seventies.The ecological disaster that it has caused, has irreperably contaminated soil, water, turf and other vegetation, in other words the host environments of humans and other mammals, as well as birds, fish, beneficial insects, and non-target plants.

Visually and materially, the jute sack represents for Mahama, the history of Ghana’s post- independence era. It also represents a material onto which various aspects of global capitalism unfold. First and foremost, the jute sack becomes a witness of the frantic pace of what many are calling disaster capitalism: the trade of goods, and the movement of materials and their destructive carbon footprint, but also the overall profile of extraction and exploitation or resources in the African continent. Secondly, it becomes a locus of human labour, the fabric being international working class. A collector of a recognisable prime matter and reference among the the sweat of humans, partially torn and marked by their various stations, they tell the history of world trade through colonialism and capitalist economy. Mahama describes them as an archival document characterized by time, form and place. Crucial to the artist’s practice is the collaborative process in which the jute sacks are collected and sorted, sewn together, reshaped and finally installed. In wrapping the Kunsthalle once more, Mahama not only discusses a gesture imprinted in art history, but reclaims it– layering past and present narratives onto our walls, and inviting us to confront the entagled legacies of art, architecture and global trade.

View more from

Nigerian Modernism – Group Show

Oct 8, 2025–May 10, 2026

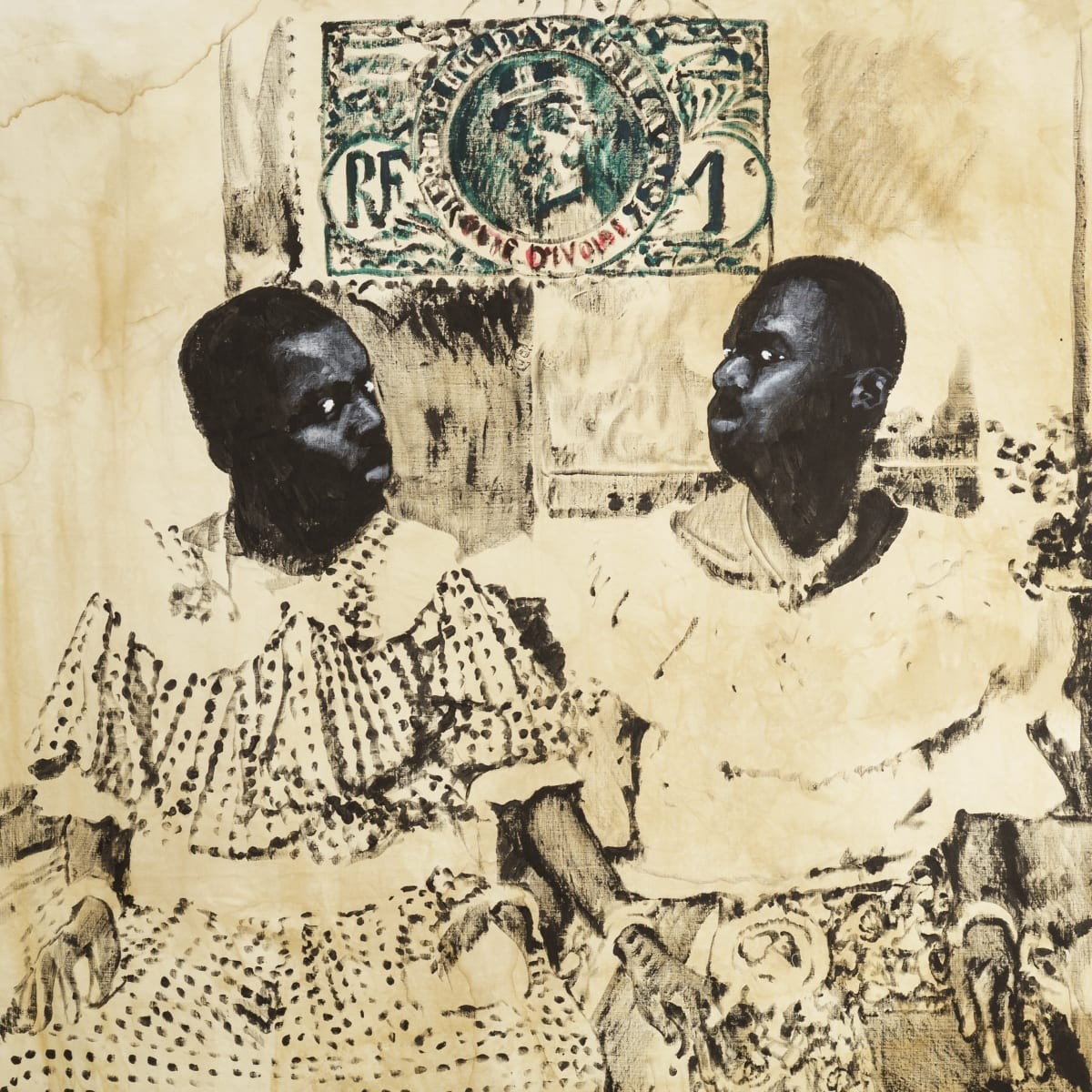

Roméo Mivekannin: Correspondances

Oct 2, 2025–Mar 21, 2026

The Writing’s on the Wall (TWTW)

Sep 13, 2025–Mar 14, 2026

Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens

Oct 10, 2025–Mar 8, 2026

ECHO DELAY REVERB: American Art and Francophone Thought – Group Show

Oct 22, 2025–Feb 15, 2026

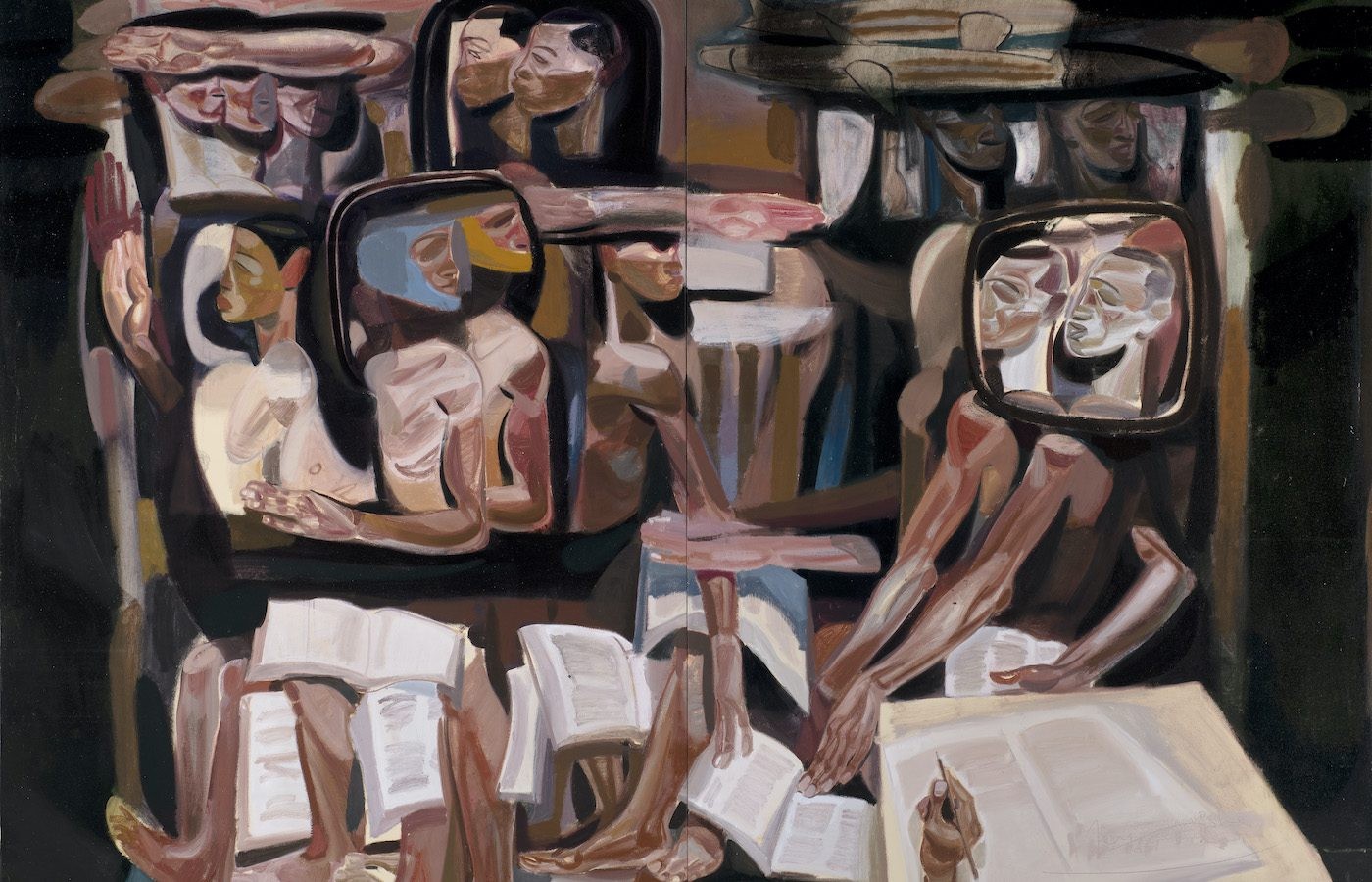

Tesfaye Urgessa: Roots of Resilience

Sep 20, 2025–Feb 15, 2026