Ebony/Curated, Cape Town, South Africa

05 May 2022 - 26 Jun 2022

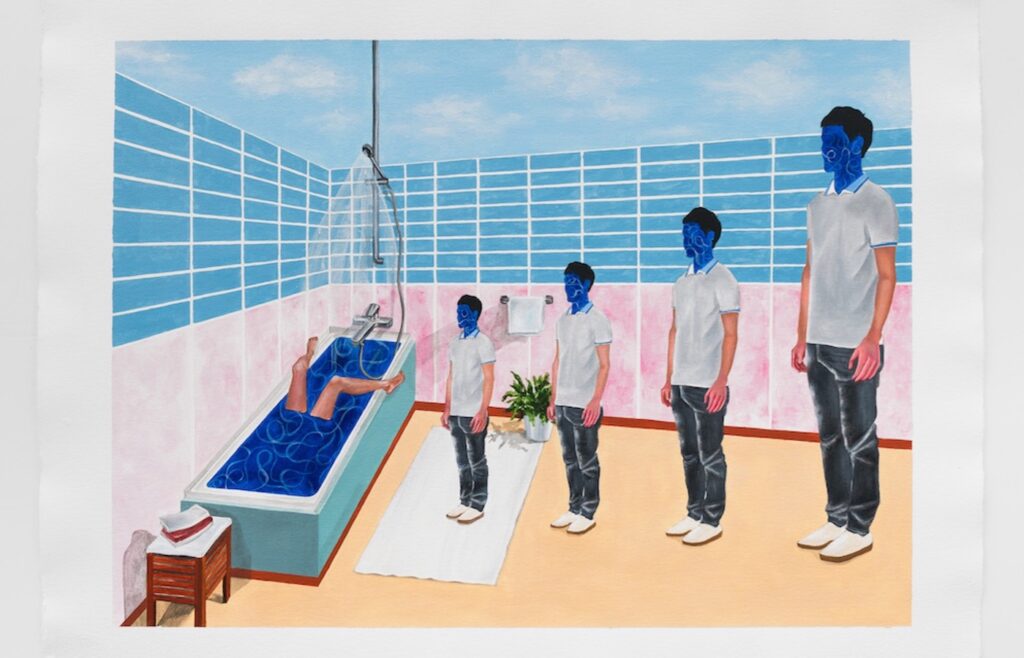

Wooju Lee, Bathroom Series 1, 2021.

A Point of Departure, curated by Christina Fortune, sets itself the task of considering the ways in which social, cultural and political life continue to move and change, despite, and because of, ongoing forms of oppression shaping modern life.

With works across media from Xhanti Zwelendada, Wooju Lee, Rory Emmett, Mikhalia Petersen, Jabu Nadia Newman, Haneem Christian and Aviwe Plaatjie, A Point of Departure employs an array of visual and conceptual strategies in asserting presence that go beyond easy, broad readings of preconceived identities. In doing so, the show considers how we use images to challenge the conditions which have created the necessity for identification. And more specifically, A Point of Departure reflects on the ways that, when intentionally played with, the burden of identity may move and shapeshift, becoming a tool of collectivity and belonging.

While identity as a point of departure may easily appear to be quite neutral, its presence relies on conditions that have historically insisted that otherness always be identified. With the invention of race, deeply violent forms of taxonomy begun to tether themselves to human bodies. Slavery, indentured labour, normalised sexual violence, the creation of bantustans, unpunished genocide, apartheid and neoliberalism are amongst its local effects, entangled historically in agendas of white ownership and profit. And whilst constitutional democracy and equality are said to define the overwhelming majority of the postcolonial world, it remains clear that the task of identification continues to be delegated to the historically created other.

On the one hand, the result of this is the frustrating impossibility of biographical escape for Black, queer, disabled, poor, and otherwise marginalised artists. However, it may also be true that in articulations of our identities, of ourselves as changing parts of social and cultural worlds, we loosen, stretch and manipulate the shapes of these burdens in our lives. How can the colonial tools of paint and photography be undone, reworked, and used to represent people who they before attempted to erase or dehumanise? And do these images help us to imagine occupying space that may still be restricted to whiteness? While identity’s meaning in the modern world is certainly steeped in violence, at its best, it may yield interesting results when appropriated, turned on its head, teased and disobeyed. The more we hammer at identity, the less secure its nefarious mechanism of taxonomy becomes, opening up the particularities of worlds that continue to survive — and maybe thrive — despite ongoing threat.