Palais de la Culture Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Bamako, Mali

30 Nov 2019 - 31 Jan 2020

By Fototala King Massassy

In December 2017, Françoise Huguier traveled to Bamako to deliver a workshop dedicated to Malian professional photographers. This workshop was entitled “On the track of Malian students sent to the East.” (Sur les traces des étudiants Maliens envoyés à l’Est) If this call is referring to historical references well seated in Mali and in the rest of the African continent, it remains enigmatic for the major part of western population.

It has been a few years that an international research program (ELITAF) is exploring certain archives that could shed the light on the relations bringing together the former Soviet bloc with African countries during the Cold War.

Tired of the French colonial tutelage, Mali joined the victorious wave of decolonisation and becomes independent in June 1960. The country is then propelled towards the international political spectrum and became the enlightened witness to the dangerous game played by world’s superpowers. For this reason Mali was forced to maintain a certain diplomatic balance while building its own power.

In this context, the URSS and their satellite countries appear to be excellent partners for Malian government—then led by the socialist Modibo Kéita— more specifically because they crystallized anti-colonial and anti-imperialistic stakes. The Soviet bloc envisioned the potential coalition with a francophone country as an opportunity to expand the span of its political, economical and military project of domination.

This brotherly and pacifist program became tangible with the first Soviet-Malian cooperative agreement, signed on 21 February 1961, laying the foundation for a military, economical, political and cultural collaboration. From 1963 onwards, the Malian government sent a few hundred thousands students to receive a training in URSS. The creation of Lumumba University in Moscow, named after the leader of the Congolese struggle for in- dependence (now renamed Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia) was part of the soviet project to regain the non-aligned countries of the “Third world.” An entire generation of engineers, doctors, lawyers and artists were trained in this university.

This cooperation also lead to the construction of numerous infrastructures on Malian grounds, notably the Administrative National School (ENA: Ecole Nationale d’Administration) in Bamako. As years went by, these type of national ventures occasioned a decrease in the number of departures to the URSS. Although the Soviet educational input was of crucial importance in Africa, Malian came to understand the limits of authoritarian politics. As for the soviet authorities, they were forced to realise that racial and cultural solidarities in their own territories are more powerful than the ones based on social class. On the eve of the fall of the Berlin Wall around 300 000 students from Africa were in URSS. A few finished their curriculum in the West in order to obtain degrees that are considered of higher value.

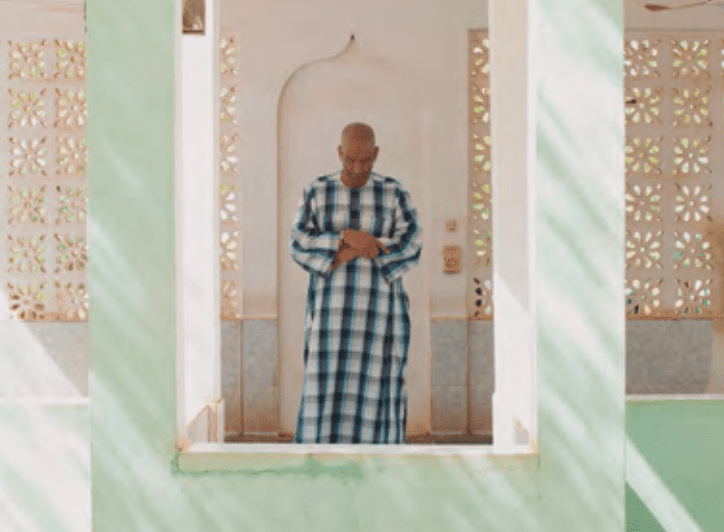

Today, these former students (Souleymane Cissé, “Birus” Oumar Diallo, Amadou Kalapo dit Bako, Bédié Diarra, Kamara Ka—Oumar Kamara—, Mamadou Habib Ballo) are for the most part retired and this very fascinating story is likely to be forgotten. That is why Françoise Huguier decided to start a research program with her students, encouraging them to get to expose the memory of their elders who lived in URSS. Thus they came to rediscover that history, and received the instruction to respond visually to these archive documents that are linked to these experiences.

CURATOR: FRANÇOISE HUGUIER | ARTISTS: SEYDOU CAMARA, FOTOTALA KING MASSASSY, MOUSSA JOHN KALAPO, SEYBA KEÏTA, KANY SISSOKO, FATOUMATA TRAORÉ | AN EXHIBITION WHICH FOLLOWS A 2018 WORKSHOP IN BAMAKO