blank, Cape Town, South Africa

28 Apr 2017 - 03 Jun 2017

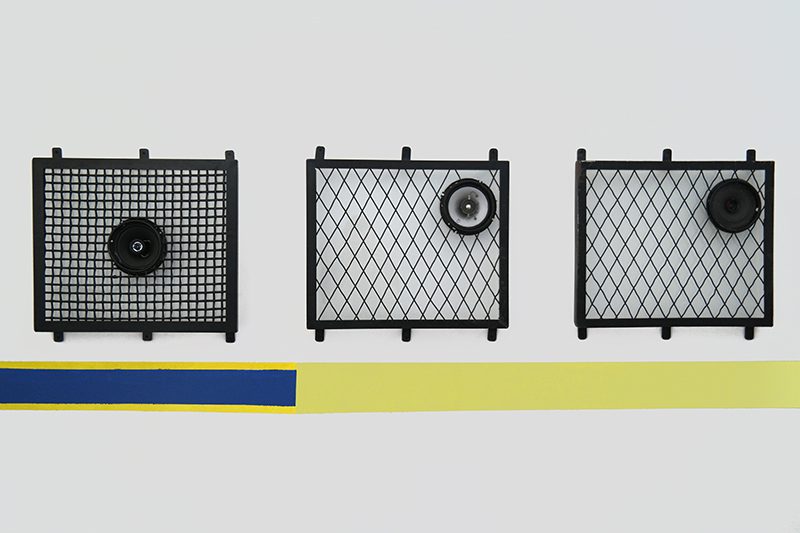

Asemahle Ntlonti, Amabali (2016) Metal, car speakers, audio and paint; installation dimensions variable

Words by Thuli Gamedze

Experiencing the work of Senzeni Marasela and Asemahle Ntlonti means moving with it across numerous landscapes, timescapes, and memory worlds. This journey is circular, and the bodies of work relay to one another histories and stories from many places in different moments and yet, in many instances, they share their allusion to a pervasive darkness and a sense of loss.

Ijeremani Lam is a mixed-media show consisting of new works from Marasela’s ongoing project that tells stories of her alter-ego Theodorah, a woman named after and inspired by the artist’s mother, whilst Ntlonti’s Kukho Isililo Somntu II mixes the historical and autobiographical story of the violence of racialized oppression in the nation.

Theodorah, who lives in Mvenyane in rural Eastern Cape, longs across thousands of kilometres for her husband Gebane, who works in Johannesburg. Her longing is so great and her patience so tender that we forget that such things are the result of brutal and crass land division in the historical formation of an efficient migrant labour system, whose disregard for love is the cause of generations of heartbreak. It is within this South Africa – the one held too tight by its false borders and the one whose labour system continues to divide lovers – that the backdrop is formed to Theodorah’s pining over her dimming memory of Gebane.

Theodorah has ‘lived’ since 2003, and she will continue to do so, for her experience of having a family separated by a patriarchal and racist regime mirrors that of millions of black people within post-colonial Africa. Framing Theodorah as a performance therefore does not seem to aptly address the heaviness and the historical and contemporary reality of the space she occupies.

I am similarly reluctant to discuss Asemahle Ntlonti’s Amabali (2016) as simply an ‘artwork’. The familiar blue and yellow stripes of a SAPS police van are painted along the gallery wall. A number of barred metal windows fitted with speakers are mounted above, alluding to the back of the van, for arrested subjects. I am reluctant to engage with it exclusively as an artwork because the presence, and even the implied presence, of a police van triggers within so many black people panic, adrenaline, and perhaps most centrally, a sense of guilt. This is an internalised double consciousness, where we must always police ourselves in response to the various ways we know we might be framed as guilty, violent, or dangerous. In this sense the black subject both occupies the back of the van, and observes themselves in the back of the van, reminding us of the perpetual limbo state of TheodorahSenzeni, another ‘multiple-single’ subject who lives both inside and outside of her body.

So with Amabali, while it is about overt violence and brutality, it is as much about internalised violence and the notion of black life as social death1. And then, yes, it is about death – the violent and hateful death that black people experience far too often. Each window of the ‘van’ plays a different sound, and Ntlonti’s recital of Chris van Wyk’s In Detention2, the chaotic sounds of RhodesMustFall activists’ clashes with police, and early musings from her younger cousins (the next generation of fighters) mingle with one another into a collective voice of sorrow. Amabali mourns for our past, present, and future, outlining at once a personal, and collective relationship that black people have with police and with policing.

Perhaps it is this simultaneous relationship with the singular and the collective, the past, present and future, that makes the work of both artists – aesthetically so different – markedly historically relevant. There is little separation between either of the artists from their work, where Ntlonti meditates and moves amongst death, Theodorah acts as the vessel for the generational heartbreak and generational forgetting in Marasela’s family. Ntlonti’s Inhlangano (2016), an installation of colourful plastic plates marked with the family names of people who live close by in the Eastern Cape, refers again to death, to the borrowing of plates for funerals, to another action of living together, eating together – amongst lives passed on from here.

So throughout the exhibition, it might be easy to talk about a feeling of ‘black pain’ or loss – loss of lives, disintegrating memory, loss of land, humanity, time, love – but we would be mistaken to end there. Theodorah is not characterised by that which she does not have, but by her modes of owning. It is the way she owns her loss and sadness, the way she writes her own history and the understanding of her own imagination that makes her interesting. Ntlonti’s persistent presence within her work, even as it operates in the realm of death feels like an assertion of life itself, speaking against the racist notion of black people as a sum of their material means, or loss thereof.

Weaving their ways through necessary darknesses and joys Senzeni Marasela’s and Asemahle Ntlonti’s explorations of the history of violence, and histories of love, pack into the confines of the gallery an impossible timespan, and a landscape stretching from the Eastern Cape to Johannesburg.

.

.

1 Social death, a term first used by Frank Wilderson, is a way to describe the mode of existence forced onto black people within a world Wilderson characterises as ‘anti-black’. In line with the Afropessimist school of thought, social death is characterised by the black subject’s vulnerability to gratuitous violence, their natal alienation, and dishonour experienced purely by virtue of their existence.

2 In Detention, 1979 by Chris Van Wyk, is a poem that alludes with a scarce palette of words, to the brutal torture and murder at ‘John Vorster’ during apartheid.