Lehmann Maupin, New York, United States

19 Jul 2021 - 17 Aug 2021

Retro Africa Gallery will make its U.S. debut this summer with a group exhibition of new works by Nigerian-American artist and writer Victor Ehikhamenor, Congolese painter Chéri Samba and African-American artist Nate Lewis, also marking Retro Africa’s first group show in New York.

Thematically building on Ehikhamenor’s practice of exploring resonances and divergences between African and African American art, Do This in Memory of Us in part examines the relationship between the ancient African kingdom of Benin, contemporary Congo DRC and the trajectory of the African diaspora in the New World, while equally featuring new works that reflect the two regions common yet divergent cultural identities, the exhibition transcends borders and creates a through line that expresses the cultural connections between the African heritage and the African American diaspora.

Known for creating immersive installations exploring universal themes of history, nostalgia, home, and spirituality, Ehikhamenor draws upon motifs from his childhood in the Nigerian village of Udomi-Uwessan and his studio practice in the United States, reflecting distinct artistic traditions and subverting assumptions of each tradition by expanding the art historical canon. He represented Nigeria in its first-ever pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2017 and, currently, four newly commissioned 60-foot sculptures are installed on the columns in front of the Pinakothek der Moderne Museum in Munich as part of LOOK AT THIS!, a group exhibition that opened in June 2021. Alongside his artistic practice, Ehikhamenor is an active advocate for African art and culture, calling for its just recognition and addressing such critical issues as the repatriation of the Benin Bronzes in editorials that have been published in the New York Times, The Guardian, and The Art Newspaper.

Do This In Memory of Us invites our engagement with narratives reflective of visions of diverse ‘Blackness’. Each exhibiting Artist borrows inspiration from the plurality of historic and contemporary African life; the flow and exchange between African and Western tradition, while developing an African singularity. Each of these Artists through their art, but in vastly different manners and media are spokespersons of different black experiences integrating specific references from their own life into their work.

Victor Ehikhamenor will showcase a series of new works that allude to Nigeria’s royal and colonial past and the forces shaping its future. The exhibition’s eponymous centerpiece, a 30 by 15-foot “tapestry,” made from over 10,500 plastic rosaries meticulously sewn together, evokes the Middle Passage, the forced voyage of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World. Storytelling is an important element of the artist’s practice as a writer. The exhibition also features the artist’s perforated series that speaks to royal intrigues, the magical realism of memory as well as sharp criticisms of history and politics. Collectively, these works connect the past with the present and speak to Ehikhamenor’s pursuit of finding new meanings for ancient African inherited beliefs in today’s world.

Born and raised outside of Pittsburgh in the town of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, currently living and working between NYC and DC Nate Lewis explores history through patterns, textures, and rhythm, creating meditations of celebration and lamentations. He earned a Bachelor’s degree in Nursing from VCU, and practiced critical-care nursing in DC-area hospitals for nine years. Lewis’ first artistic pursuit was playing the violin in 2008, followed by drawing in 2010. Since 2017 he has lived and worked in New York City. Interested in the unseen, his work is driven by empathy, and the desire to understand nuanced points of view. By altering photographs, Lewis aims to challenge people’s perspectives on race and history through distortion and illusion, treating paper like an organism itself, he sculpts patterns akin to cellular tissue and anatomical elements, allowing hidden histories and patterns to be uncovered from the photographs. Lewis approaches subjects and imagery from a diagnostic place with the idea of utilizing diagnostic lenses and contrast dyes. Lewis’ work has been exhibited in Plumb Line: Charles White and the Contemporary at The California African American Museum, The Studio Museum in Harlem, The Yale Center for British Art, 21c Museum Hotels,The Armory Show, Paris Photo, Expo Chicago, Art Untitled Miami Beach, and is currently in Men of Change: Power, Triumph, Truth, touring with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Services.

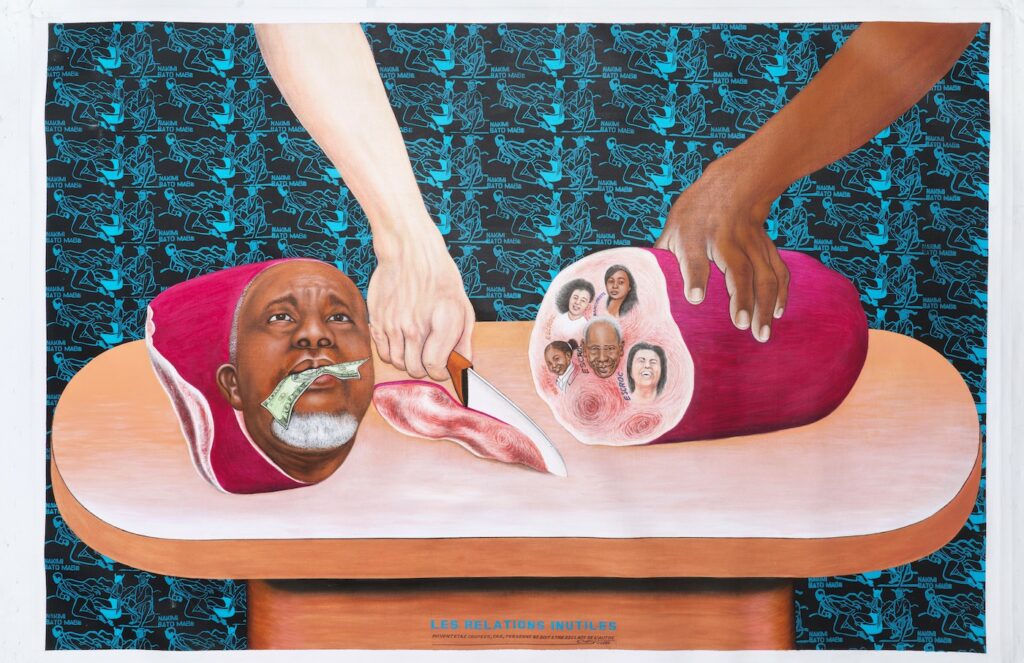

Chéri Samba was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Currently living and working out of Kinshasa, Samba began his career as an artist without any formal education, starting out as a sign painter before joining Moké and Bodo, along with his younger brother Cheik Ledy. Together they run one of the most popular schools of painting. At the age of sixteen he left his village to find work as a sign painter in the capital Kinshasa, where he began to develop a body of works that combined representational painting and text. Samba’s paintings of this period reveal his perception of the social, political, economic and cultural realities of Zaïre, exposing all facets of everyday life in Kinshasa. The paintings to be presented in this exhibition, courtesy of MAGNIN-A Paris, “J’aime bien son dos”, “Le Risque du métier”, “Les relations inutiles”, “Je ne suis pas aimé”, offer a running commentary on popular customs, sexuality, AIDS and other illnesses, social inequalities, and corruption. From the late 1980s on, he himself became the main subject of his paintings. For Samba, this is not an act of narcissism; rather, like an anchor on TV news broadcasts, he places himself in his work to report on what it means to be a successful African artist on the world stage.

A self-proclaimed “‘undisciplinable’ hero,” Chéri Samba likes to throw people off track. Through his words, he cancels out the visual polysemy of his paintings, while artificially proposing a singular reading. This is a way of blocking subversive interpretations, of protecting himself by pretending not to engage in politics, and of maintaining control over the narrative of his life and work. It is also a way of keeping scholars and curators from attaching their own overly normative (or in any case insufficiently de-centered) narratives to his work—or from otherwise bending it to their needs.

In his paintings, he comments on himself. He questions and establishes the evolution of his material conditions, his status as an artist, his own fame, the level of that fame, his own place and that of his peers in the art history of his country—and within the larger discipline of art history.