The Project Space Cultivating a Community of Artists in Harare

28 March 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

5 min de lecture

Founded by three creatives, Village Unhu in Harare, Zimbabwe, is an art space that nurtures artistic local talent. Since its inception a few years ago, it has offered several residencies, workshops, internships, art lessons, and exhibitions. Our author Tinashe Muchuri met Misheck Masamvu, one of the founders, to find out how this success story came to be.

.

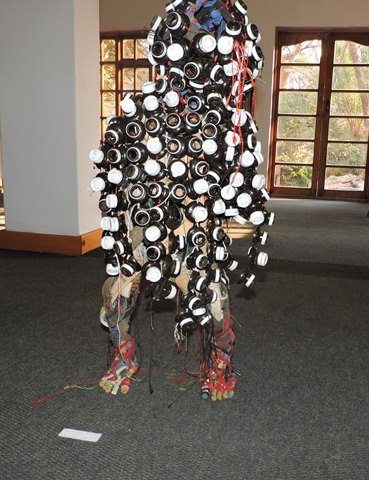

During the 2017 International Conference on African Cultures (ICAC) guests were afforded a tour of the creative art hubs in Harare. Village Unhu was among one of the many spaces toured. Its group show at the time, Immunity, chronicled society’s challenges, abuse of power and drugs, and the obsession with greed. Some of the artists exhibiting were Tawanda Takura with his Unresolved series and Evans T. Mutenga’s Work in Progress.

</a> Tawanmda Takwira's Unresolved. Photo: Tinashe Muchuri</figure>

Since then, Village Unhu has relocated to a smaller permanent space on 1 Rowland Close, Milton Park in Harare at a two storey lodge building turned into a creative open art space by Georgina Maxim, Gareth Nyandoro, and Misheck Masamvu. It offers residencies, workshops, internships, art lessons, exhibitions and meetings. The discussions that take place here revolve around the philosophy of unhu/Ubuntu/vunhu the village was started by people with similar backgrounds, almost like orphans. Having gathered experience at Gallery Delta, where he did not arrive as an artist but was adopted as a child, Masamvu says Village Unhu was born not as a collective but as a family. The founders picked a village setting, in the rural sense of it, and Unhu became the fibre that unites people. With changing times, Masamvu says the village is now focusing on new experiences on art production markets, how to present oneself, how to experience art, the meaning of art, how to validate art, how to be independent, how to consume art, and how to make art part of the heritage.

The space is run with a family structure: residencies function similarly to when receiving a visitor in one’s home, while exhibitions and workshops resemble kitchen parties. The village’s Greendale studio houses an archive with information about all the artists who have visited. Refurbished old cars are often parked outside, which could make the space look like a car dealership, but a jovial Masamvu dispels my misconceptions, saying the cars are close to his broken nature and stand as symbols of resistance because they have withstood the passing of time. Most of these cars are 30 to 40 years older than him.

</a> Misheck Masamvu in front of an old car. Photo: Tinashe Muchuri</figure>

Bringing the old cars back into the arena, “rejuvenates, gives a new vitality of power, and makes the old generation feel their existence is no longer obsolete,” he says. “They have a lot to contribute, and whatever they are contributing is something the history books might have omitted.” On a personal level, Masamvu has found a therapeutic process that allows him to direct his physical energy towards being useful to society. Fixing a car made him realise that he could start to fix himself and make its story part of his story. He neither believes in hiding his scars nor in celebrating every scar as a moment of survival; instead, he wants to learn from why he got the scar in the first place.

Village Unhu is mainly self-funded as the founders felt that funding is misleading, however, certain projects within the village receive funding from outside. Though the village cherishes collaborations, the artists demand that other galleries openly recognize and acknowledge where they come from. Masamvu labels galleries that do not recognize the base the selected artists come from as “the biggest enemy of art.”

“How much of the art are we making? Are we just offloading to the international market? How much of it are we keeping here for ourselves, for the artists and for the next generation? Are we only keeping the bad art or even the most successful art, or are we keeping only the work in progress?” Masamvu asks. “So we begin to have conversations on why we need to create a museum, a gallery. We need to confront whatever is coming out of the universities and say that curriculum is not sustainable, perhaps we need to have an investment portfolio, perhaps we need to realize that art is currency that at the end of the day needs to be adopted as a bond system, that the bank and everyone in this country need to look at it as a form of investment, perhaps art forms a kind of collateral.” Within all these conversations, Masamvu says they are forced to evolve as a space and also engage with the business structure available around them because today’s artist is no longer just an artist but needs to engage with all these structures. As storytellers, Masamvu stresses that they are more into seeing how artists survive in a group and what mechanisms exist to help each other onto the same path.

However, they are glad there are members of the village who have become successful and have begun to create other spaces elsewhere. “We are beginning to open new chapters where people are beginning to choose who to work with,” Masamvu says, laughing. “Those are some of the stories we need to ponder, rewrite, correct, and recite.”

Tinashe Muchuri is a performing poet, actor, writer, based in Harare, Zimbabwe and a student from the C& Critical Writing Workshop which was held in Harare in September 2017 and made possible by the support of the Ford Foundation.

Plus d'articles de

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Esperanza de León: Curating Through Community Knowledge

Plus d'articles de

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

I Am Monumental: The Power of African Roots