Sasha Huber: Honoring Lost Memories

Despite their colonial history, the Nordic countries don’t have as large communities of people of African descent as other areas in Europe. This has contributed to many Afro-Scandinavians growing up in isolation with a complex sense of belonging. Today, however, several Afro-Scandinavian artists are embracing their layered histories and identities in their work. In the series The Nordics: Out of the Shadows, we meet some of them. Sasha Huber is a Swiss-Haitian-Finnish artist based in Finland. Our author Sheila Feruzi asks about her art practice rooted in remembrance and representation, including renaming a mountain in the Alps and honoring the victims of the Transatlantic and Mediterranean Middle Passage.

Contemporary And: Like many other Scandinavian countries, Finland is known for social progress, economic stability, public safety, freedom, and equality. Yet a 2018 study commissioned by the EU’s Fundamentals Rights Agency found Finland to have the highest rates of race-related harassment and violence in Europe. Could you describe your experience living and working as an artist of color in Finland?

Sasha Huber: When I first moved to Finland in 2002, due to my husband being Finnish, I did an MA in graphic design. I was one of very few foreign students of color here. I found Finland an ideal ground to start my art practice in peace, but there was a sense of loneliness – my art community dealing with similar issues as I do were abroad. Eventually I found my community here as well though, to some extent. Meanwhile we became more visible and organized. With my husband I initiated exhibitions and spaces. Sadly, those initiatives weren’t always supported, even though they were novel to the scene. The powerful need of art authorities and private institutions to own artist-run spaces and patronize those running them has become very visible here recently – to the degree that we had to close our own multicultural space.

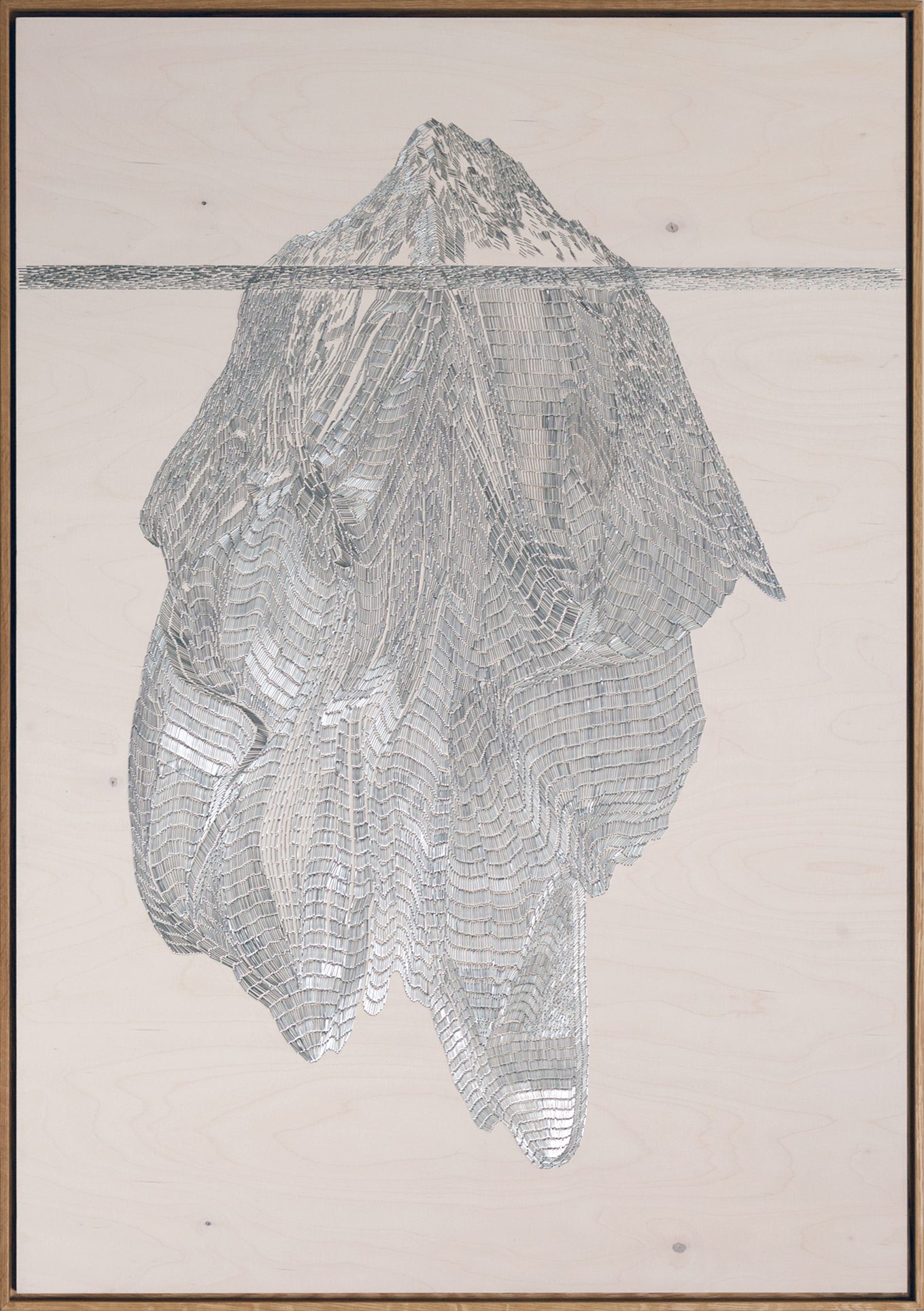

Sasha Huber, Iceberg I, 2020. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Katja Hagelstam/LOKAL

At the beginning, I knew just one other artist from the Caribbean Diaspora, Elie Noël (1962–2010), who was from Haiti. He told me that if you are Black in Finland it is very hard to find good work. He moved from the US, where he worked in IT, and all he got to do in Finland was cleaning jobs, beside studying art. The survey you mention said that 63% of participants stated that they had experienced race-related discrimination, especially in the labor market and housing. People with foreign-sounding names, even those born in Finland, have it more difficult. Afro-Finns have a challenge to live here in a white-normative society with structural racism in all fields, especially in education.

C&: What are the opportunities or challenges you have faced specific to Helsinki?

SH: Due to underrepresentation of people of color in the arts, I happened to be the one to introduce the decolonial discourse, which was not a discussion here in the early 2000s. It was interesting to be able to bring something new to a place and possibly inspire others to learn more about histories they hadn’t considered.

C&: Which art projects have brought you closer or further from your roots?

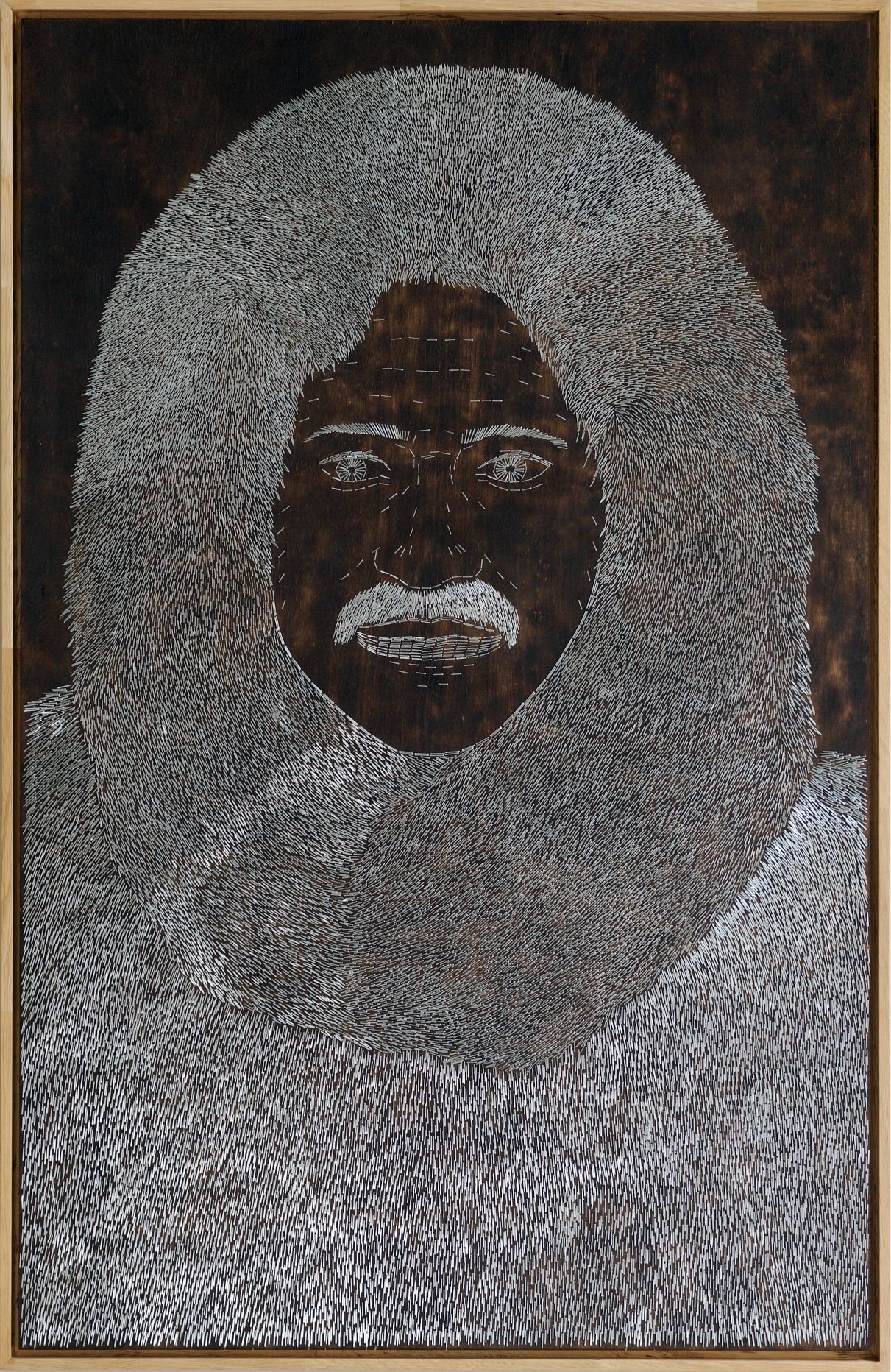

SH: I am from Switzerland and my mother is from Haiti. In the 1960s part of my family migrated to New York because of the dictatorship in Haiti. I visited Haiti with my parents and sister in the 1980s when Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier was still ruling. I always had an urge to go back, but by then my mother would not allow me due to the political problems. During my studies in Helsinki I had the idea of working with the staple gun. I realized it’s like a weapon. The weight and sound of it, and the way you have to protect your ears and eyes while using it. This powerful symbolism enabled me to relate it to trauma and violence. I wanted to react to not being allowed to go to my mother’s home country. It brought me closer to her heritage and made me learn more about that history. I decided to portray people responsible for the troubles in Haiti and called the series Shooting Back – Reflection on Haitian Roots. I portrayed Christopher Columbus as a starting point, using thousands of staples. That was my first art project and the beginning of my exploration of colonial history. It became the seed for all the reparative “wake work“ that followed.

Sasha Huber, The Firsts – Matthew Henson, 2020. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Katja Hagelstam/LOKAL

C&: Since 2007 you have been part of the Demounting Louis Agassiz campaign, which sheds light on the sinister history surrounding the celebrated Swiss glaciologist.

SH: My sister gave me historian and activist Hans Fässler’s 2005 book Reise in Schwarz-Weiss – Schweizer Ortstermine in Sachen Sklaverei (Travelling in black and white: Swiss on-site appointments concerning the slave-trade). By then it was only the second book ever written about Switzerland’s relationship to the slave trade and colonial history. I was amazed by it and contacted Fässler to meet him to speak more. Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), was a topic in the book. He was a very well-known glaciologist. Seven species, over eighty places around the world, and one on the Moon and one on Mars are named after him. But the fact that he was one of the most significant “scientific” racists of the 19th century was left out. In 1846 he became director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology and Geology in Harvard. After moving to the US he commissioned photographs to be made of enslaved people naked from all sides, which I assume must have felt very humiliating. They were supposed to prove the “inferiority of the black race.” Research has showed that Hitler’s ideology can be traced back to Agassiz.

Hans felt that this positive characterization of Agassiz was the mistake of insufficient history-writing. As Agassiz’s centennial was celebrated in 2007, he decided to found Demounting Louis Agassiz with a transatlantic committee made up of politicians, journalists, artists, and activists. I was one of the artists. The aim was to rename the Swiss mountain Agassizhorn as Rentyhorn. Renty was a Congolese man photographed for the Slave Daguerreotype Series, along with his daughter Delia. In 2012 we were contacted by his descendant Tamara Lanier. In March 2019 she filed a lawsuit against Harvard University to get ownership of her family’s photographs from the Daguerreotype Series. Their reaction is pending.

Sasha Huber, Iceberg II, 2020. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Katja Hagelstam/LOKAL

C&: Your current solo exhibitionThe Tipping of the Iceberg atGallery Lokal in Helsinki is now available to see on Instagram. What are its themes?

SH: This exhibition connects thematically with the Demounting Louis Agassiz project. It also relates to the Eurocentric industrial origins of the climate crisis. The tip of the iceberg can be seen in the visible climate crisis, but also indicates the submerged weight and scale of fossil extraction and the energy and labor hidden inside the history of colonialism.

C&: How do you get the visual nuances in, for instance, The Sea of the Lost?

SH: The metal staples are all mono-color and I use them in up to three different sizes. Depending on the angle of the light hitting the metal, it can create a three-dimensional appearance. The Sea of the Lost commemorates people who didn’t survive the Middle Passage during the Transatlantic slave trade, similar to Mediterranean Middle Passage happening now, as we speak. I used about 200,000 staples. I never shoot for purely aesthetic reasons.

C&: Where do you have your strongest sense of belonging?

SH: Finland is the place where we started our own family and where I became who I am as an artist. This gives me a strong sense of belonging. I also belong where the rest of my family is: in Switzerland, the US, Canada, and the Caribbean. During longer artist residencies I often also develop a strong sense of belonging through interactions and friendships built during intense learning, sharing, creating, and giving. This happened for me particularly in Brazil and in Aotearoa New Zealand. I left a piece of my heart in those places.

Sheila Feruzi is an afro-Norwegian screenwriter and film producer currently based in Bergen, Norway. Through the upcoming media company Vuma she is developing podcasts and digital media solutions that will highlight content by multicultural creators in Norway.

En Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

En Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George