Sarah Ama Duah: A Journey Towards Building Contemporary Monuments

The artist purposefully contributes to the sculptural visibility of various Black narratives as part of Germany's history and culture of remembrance.

Black cultural production has been coming out of the German-speaking world for centuries, and it has been as diverse and distinct as the various countries and their regions. Here we offer a series which highlights artists of different generations with strong ties to these geo-cultural territories. Sarah Ama Duah is an Afro-German artist and fashion designer based in Berlin who explores the relationship between body and sculpture, focusing on historical narratives and artifacts of cultural memory.

Tania Luz Olivares Achach: It seems to me that you carefully observe western traditions of remembrance, build on them, question them, and eventually produce an additional narrative in the form of an artwork. Even though the material format of the work has morphed from garment to performance and now sculpture, your practice can be thought of as activism. Is that something you identify with?

Sarah Ama Dua: I consider my artistic practice to be a place of materialized reflection into which I invite others. I try to process my own experiences through my work, which is as personal as it is political. I go to the studio, make work, reflect, and go back to stretch moments which I couldn’t process in real time. I take a closer look at the details and eventually translate everything into an artwork.

Sarah Ama Duah, Sculpture Dresses, 2019, Fashionclash Festival, Maastricht. Photo© Pasarella Photography

TLOA: How did you find your creative practice?

SAD: That’s a difficult question. I can say that my mum encouraged me to believe in my abilities and practice. That’s the foundation. I found it easier to express myself through materials than words. Now, I would add that outside of home people were more attentive towards the things I made rather than to what I had to say. I guess it was also a strategy of finding ways to communicate within my environment.

TLOA: You have often worked with hair, for example. What drew you to unconventional materials?

SAD: I studied fashion with Viktoria Greiter. Rather than anything to do with fast fashion, we followed an artistic approach towards dress making. We took our time, treating a dress as sculpture while considering wearability in a broader sense. The main material for my BA degree collection was artificial hair. I had started wearing my afro again and the braids became part of the work. The series was inspired by the African art and practice of hair making, my own autobiography, and Martin Margiela’s output. It was the first time I consciously weaved my personal experience into my work. I choose the material based on its characteristics—its surface, its philosophical and cultural implications and availability. I asked myself questions like: What does it do? How can I process it? What does it need? In what ways can I transform it? The collection was showcased at Ghana Fashion Week 2012, which meant I got to travel to Ghana after a twenty-year gap.

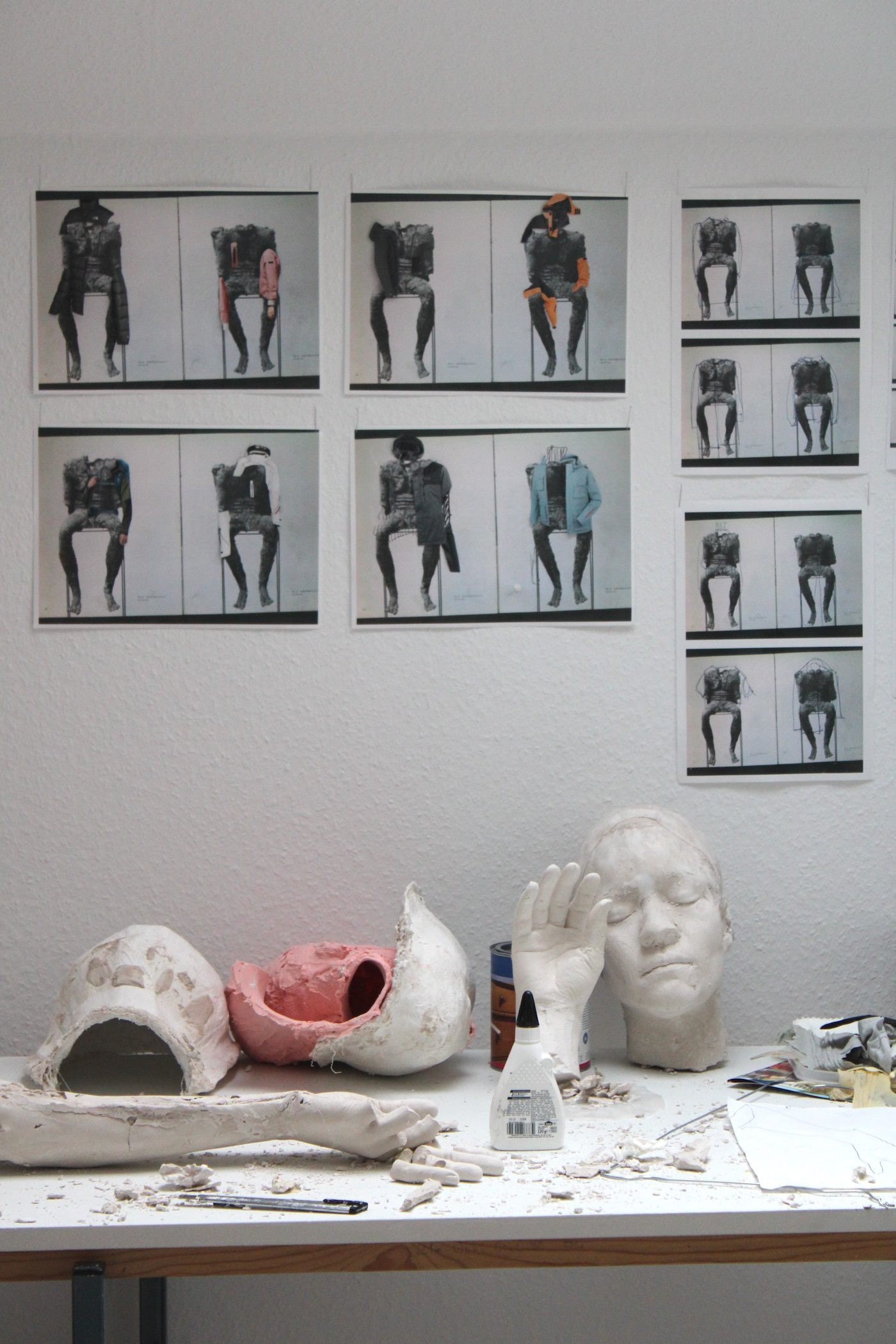

Sarah Ama Duah, Studio View, 2018. Courtesy of the Artist

TLOA: Were you thinking about the wearer’s movement at all when you were constructing the clothes?

SAD: This has been the biggest struggle for me every time. The space of discrepancy when “body meets dress,” as Rei Kawakubo has put it. My dresses have become more and more sculptural over the years. Bringing the body and its agency together with my dresses in a way that was functional within a runway setting was challenging. It made sense to explore the discipline of sculpture within the artistic sphere.

TLOA: You used your own body for your performance to build, to bury, to remember,2020- 2023. What was that like?

SAD: For a Black female body in Germany, the white gaze is omnipresent. Because there is lot of uninvited staring that you cannot control, it feels like you are both hyper visual and almost invisible. Inviting people to look at me within a public performance felt empowering and vulnerable at the same time. The series started as a solo and evolved into a group performance—we were four performers at Galerie Wedding in 2022.

Sarah Ama Duah, To build, To bury to remember, 2022, exhibition view, Galerie Wedding, Berlin. Photo©Tomas Eyzaguiere

TLOA: How did you structure that version of the performance?

SAD: It was part of a two-person show titled Existing Otherwise with artist Ato Jackson. I exhibited my latex monuments without performers and used them as the base for my performances at the opening and closing. We performed during the evening vernissage for about an hour in the crowded gallery, while the finissage happened during daylight so people could pass by, walk in and out, and have more time to arrive.

TLOA: The invitation to be seen is powerful, especially in the German sphere where Black histories have often been overlooked.

SAD: As an Afro-German artist and member of the Afro-diasporic community, I want to contribute to the visibility and sculptural representation of our various narratives as part of Germany’s history and culture of remembrance. There needs to be more space for out visions and perspectives on history. I highly recommend Natasha A. Kelly’s books to learn more about Black German history. I am still learning.

Sarah Ama Duah, To build, To bury to remember, 2022, exhibition view, Galerie Wedding, Berlin. Photo ©Tomas Eyzaguiere

TLOA: What has that been like producing art in a western context and having a decolonizing mindset?

SAD: It has been a journey. I’m socialized within a western context—it took me a while to realize that. I was born and raised in Germany. Decolonizing my mind and trying to practise the best way I can is never-ending. When I started working around the topic of colonial monuments in Europe, the discourse was already around. Decolonial projects like the ISD (the Black People in Germany Initiative) have been addressing colonial legacies since the 1990s.

One specific event that I was following, through the media, was the demolition of a colonial sculpture in Bristol in the UK by Black Lives Matter activists. That moment when the statue came down, sunk into the river, and became invisible. I thought about how to stay in that moment, that powerful gesture of removal, the physical absence of that figure and the empty pedestal. The title of my performative research series to build, to bury, to remember emerged from that thought process.

TLOA: Were you thinking about making a monument for an art space or a public space?

SAD: So far I have produced work for inside. Producing a monument for public space would provide broader visibility but it would also come with a lot of restrictions. It’s a different way of working. I’m now thinking of Nando Nkrumah’s artistic intervention at Schloss Charlottenburg from 2023—he really managed it well, creating meaningful work working with those restrictions. What strikes me is that such invitations are mostly temporary.

Sarah Ama Duah, daffodils for feast day, 2024, exhibition view, HKW, Berlin. Photo©Jana Edisonga

TLOA: One stood at eye level with your sculpture at Haus der Kulturen der Welt earlier this year. Was that something you thought about: taking the person off the pedestal?

SAD: For the narratives explored in the exhibition Echoes of the Brother Countries there never was a pedestal that could have been taken away. Stories of migrant labor within the GDR were shaped by the state propagating an image of solidarity and Völkerfreundschaft (“friendship between peoples”). I wanted to create an ode to the woman whose bodies were regulated within the context of GDR migrant labour.

Placing the figure at eye-to-eye level allowed space for connection. It felt more confrontational than looking up. HKW’s architecture is very dominant. During a conversation about the work my professor, artist Jimmy Robert, used the phrase “inscribing it into the wall.” I wanted the piece to become part of the architecture, spreading the birds as an extension of the figure, taking up space.

TLOA: You once said that “monuments either make you feel at home or they don’t.” What is your relationship to monuments like?

SAD: Figurative monuments profoundly shaped my perception of what art in public space should look like: male military figures on horses, larger than life and on pedestals, history carved in stone or cast in bronze. I was impressed by the craft. When I learned about their historical context, that they are mostly glorifications of colonial warlords, and how they propagate imperialist ideologies, I looked at them differently. That dominance has always been felt.

@sarah_ama_duah

Tania Luz Olivares Achach (b. 1992; Mexico City) is a Berlin-based curator and founder of neithernor.eu. Olivares Achach graduated with a Batchelor of Fine Arts from Central Saint Martin’s (London) in 2015 and later with a Master in Theory and History of Photography from Folkwang University of the Arts (Essen) in 2021. Her curatorial work focuses on practices addressing cultural and identity politics through photography, performance and installation.

Fonction

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room : annotations sur l’art, le design et les savoirs diasporiques

Performance art

Filipa Bossuet: Performance as Conversation, Intimacy as Power

Anaïs Cheleux : Relier l'identité caribéenne par la photographie et la performance