Kosisochukwu Nnebe: Exploring Ancestral Connections

The artist and curator discusses how the positions of marginalized people give us access to particular forms of knowledge about our societies.

It’s a rainy day in Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal, where Kosisochukwu Nnebe is, and I have thunderstorms and gloomy weather in my Toronto surroundings. Hearing the storms in her background intensifies my longing for the rain in my skies to drop. We talk about her being Nigerian-Canadian with Igbo ancestry and about her move from Nigeria to Gatineau, Quebec at the age of five. We explore her recent exhibitions and works, circling the issue of Blackness as being more than its violent origins, embracing the versatile use of language and food as tools for ancestral connection. We discuss an artistic practice that traverses spatiality and coded visual lexicons, unearthing diverse potentials of Black futures rooted in anti-colonialism – and her current experiments with cassava as a tool for knowledge transmission and connection.

</a> Self-portrait of Kosisochukwu Nnebe, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.</figure>

Tamunoibifiri Fombo: I am glad I can practice my Igbo today. Kedu?

Kosisochukwu Nnebe: Ọ dị mma.

TF: How would you currently describe your practice?

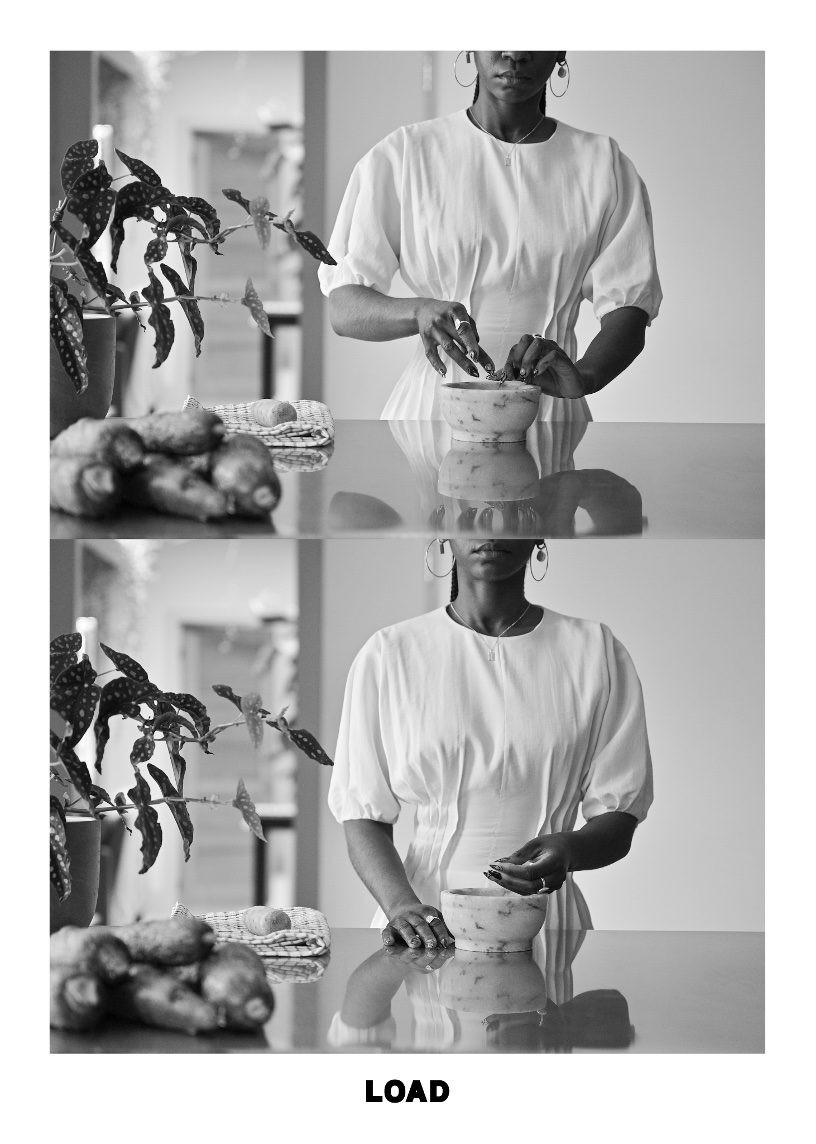

KN: My practice has increasingly felt very spiritual – I’ve often felt like there's a message being channeled through me. I think being an artist is such a blessing and a joy, and that fundamentally artists are portals and vessels. Messages that have come through most clearly as of late have been about conjure women and root workers of the past whose engagement with Obeah and other kinds of spiritual traditions, originally from West Africa, helped them and other enslaved Africans to survive and make sense of the new world they found themselves in. Traditions that were syncretized with Christianity and other Indigenous forms of spirituality. These women, many of whom were forced to perform domestic and care labor in the homes of their enslavers, learned how to make use of cassava to poison their masters in a total rejection of their own dehumanization.

I have an urge to share those stories, to honor these women, that knowledge, that work, that ability to alchemize cassava – and the natural environment in a broader sense – into whatever is needed. If you need food, it becomes food. If you need it for a weapon, it becomes a weapon. It was a form of solidarity between humanity, plantlife, and the natural environment around these women. It was a translation and transmission of knowledge between Indigenous people – who first learned how to make the naturally poisonous cassava into an edible food and conversely into a weapon – and enslaved Africans. My work has been channeling those transmissions that happened. I find this message relevant for us, living as we are in the wake of transatlantic slavery. I'm excited to further explore these ideas, as well as ideas around the trickster and marooning, as part of a seven-week residency in Maroon Town Jamaica this fall.

</a> Kosisochukwu Nnebe, an inheritance. 2022. Video still. Courtesy of the artist.</figure>

TF: How does your practice align with Black feminist standpoint theory and knowledge transmission? What aspects of knowledge are particularly significant or resonant in the context of your work?

KN: Knowledge is the fundamental thread intertwining various aspects of my practice. I'm interested in exploring and embodying standpoints that have received less attention but are crucial in validating the knowledge that emerges from specific circumstances. This goes beyond viewing people solely as victims to focus on understanding how they navigated and at times subverted insurmountable situations.

One of my works is an installation that can only be fully experienced by stepping onto a podium modeled after a slave auction block and looking through sheets of red plexiglas hung around it. From that position you can decipher hidden messages and images. What I'm asking is: what kinds of perspectives and knowledge can only be understood from particular social – but also physical and geographic – positionings? It's about aspects of what is seen and what can be learned from particular vantage points as a form of inheritance.

A lot of the time when people think of Blackness in Canada, it’s marked by a presence or an absence, this back and forth between visibility and invisibility. In my work, I’m interested in playing around with and rethinking what invisibility can mean and feel like when understood as withholding and opacity. I always found a lot of solace in hiding or not being seen; it gives you access to unique perspectives and you can just watch things play out in ways that uncover their hidden functionings. This is part of what Black feminist standpoint theory is about, the ways in which the positions of marginalized people give us access to particular forms of knowledge about the societies we find ourselves in. A lot of my work is about that. Engaging with things that might seem insignificant to others and turning them into objects and realities of supreme significance.

</a> Kosisochukwu Nnebe, Installation view at I want you to know I am hiding something from you / since what I am is uncontainable. Artexte, Montreal, Canada. 2022. Courtesy of the artist.</figure>

</a> Kosisochukwu Nnebe, Installation view at I want you to know I am hiding something from you / since what I am is uncontainable. Artexte, Montreal, Canada. 2022. Courtesy of the artist.</figure>

TF: What are things you have been turning into supreme significance in your artistic practice?

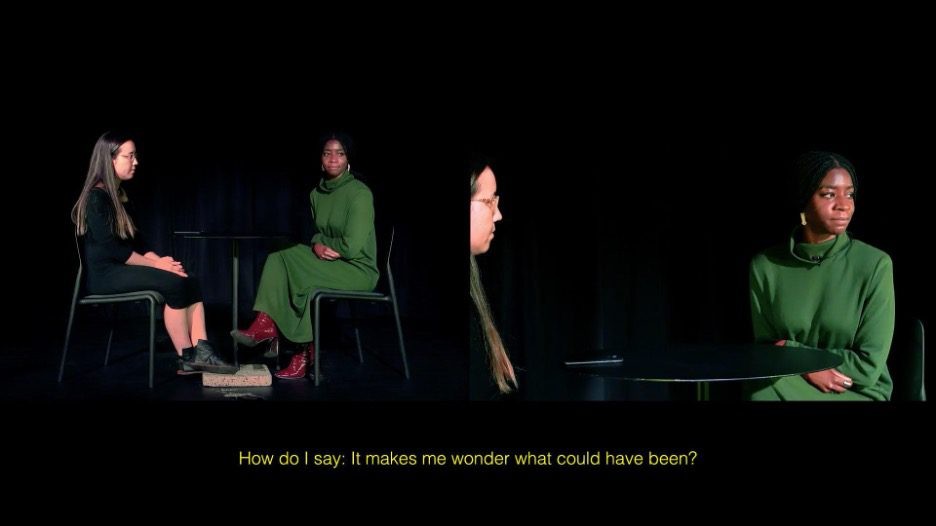

KN: I’ve been looking at how language helps us understand imperialism in ways that are not only rooted in the past but help us think about different kinds of knowledge – how they are held in language and can be unearthed to imagine a new future. As explored in The Ancestors Are Meeting Because We Have Met, my video work in which Katherine Takpannie, an Inuk artist, and I attempt to speak to one another in our respective mother tongues, the restitution of our ancestral language is restitution of our other ways of knowing.

</a> Kosisochukwu Nnebe, Ndi nna nnanyi na ezuko maka na anyi zukoro / Imaaqai, suvulivut katittut katisimagannuk / The Ancestors Are Meeting Because We Have Met, video, 22:01, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.</figure>

TF: I am inspired by the way you talk about your practice. You often talk about intentionality. What does that mean to you, and how do you approach your craft and your life in that way?

KN: It's interesting to hear other people's perceptions of you – because in my mind, I'm just chaotic. But there is a lot of intentionality and I think I have the opportunity to be even more intentional now. I have been working with the government since I graduated from my undergrad, so I am divided between two worlds: my policy work and my art practice. And while that has been sustainable, I now feel the need to devote more of my time towards building my craft. To carving more space for rest. I want whatever energy I am putting towards a full-time job to go towards my practice and to be more consistent. I think that approach will allow me to have more energy and more life to put into my practice – and hopefully to go back to reading more. A lot of my work is based on extensive research. Being a portal (and a trickster), and being able to hear and channel messages, means you have to be very clear-minded – and that requires space.

</a> Kosisochukwu Nnebe, An image of the trickster at The explosion that will not happen today, 2022. The Bows, Calgary, Canada. Courtesy of the artist.</figure>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">Tamunoibifiri “Firi” Fombo is committed to the development of the creative and cultural sector in Africa and the diaspora. </span><span style="font-weight: 400;">As a consultant, Firi collaborates with diverse creatives, organizations and stakeholders to formulate strategies and processes that bring creative visions and development to life. Firi’s curatorial and artistic practice focuses on documenting the layers of human life through photography, writing, audio and placemaking. </span><span style="font-weight: 400;">Tamunoibifiri recently founded IbifiriWari, where they provide artist development, advisory and creative consultancy services aimed to support the development of the creative and cultural sector. </span><span style="font-weight: 400;">Firi is currently based in Toronto but works globally.</span>

En Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

En Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George