In Complicity with a Great Documenter

In 2019 young South African curator Thato Mogotsi had been invited by the Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam (FOAM) to speak about Dr. Santu Mofokeng’s body of work. In the wake of his recent passing C& re-publishes her reflections on his captivating images and his far-reaching impact on a current generation of Black South African image-makers and practitioners.

“Santu Mofokeng’s oeuvre is notably distinct within the South African photography canon, a fact revealed itself to me almost like a breakthrough.”

I came-of-age in a country where photography was weaponised in very specific ways; and I received training in photojournalism and documentary photography at the Market Photo Workshop. Yet what I encountered in Mofokeng’s work was a complication of my own early education – in understanding of photography as a language. After about eight years of working at the picture desk of a national weekly newspaper, in daily pursuit of the best front page news picture for the day, increasingly I found myself interrogating the role of photojournalism in shaping the contmporary South African narrative. While the Apartheid government had used photography as a tool for propaganda, local resistance movements had looked to Black photographers to document the regime’s violent suppression of their activism and consciousness-raising efforts.

The images of Mofokeng’s own contemporaries – other seminal photographers such as Peter Magubane and Alf Khumalo –have since universally historicised the realities of the Black resistance that persisted in townships and urban centers across the country. So much so that terms like ‘struggle photography’ have been used often to define this canon – as it shares a confrontational typology that effectively, alongside news reportage, alerted the outside world to the atrocities of the Apartheid government. But what of the daily lives of the every man and woman in communities whose stories were marginalised in this overarching narrative? Mofokeng’s work, for me, offers several reflections on that very question.

While he began his career as a street photographer and worked as a photojournalist in the 1980s, Mofokeng quickly found the pressures of newsroom deadlines and conventions of reportage very limiting to his sensibilities. In his own words – in a 2010 interview with Tamar Garb[1] – Mofokeng spoke of his approach as that of ‘making pictures of people I had to live with.’ His later work thus seemed to foster a contemplative and restorative gaze based on the proximity he had to his subjects – an insider’s perspective.

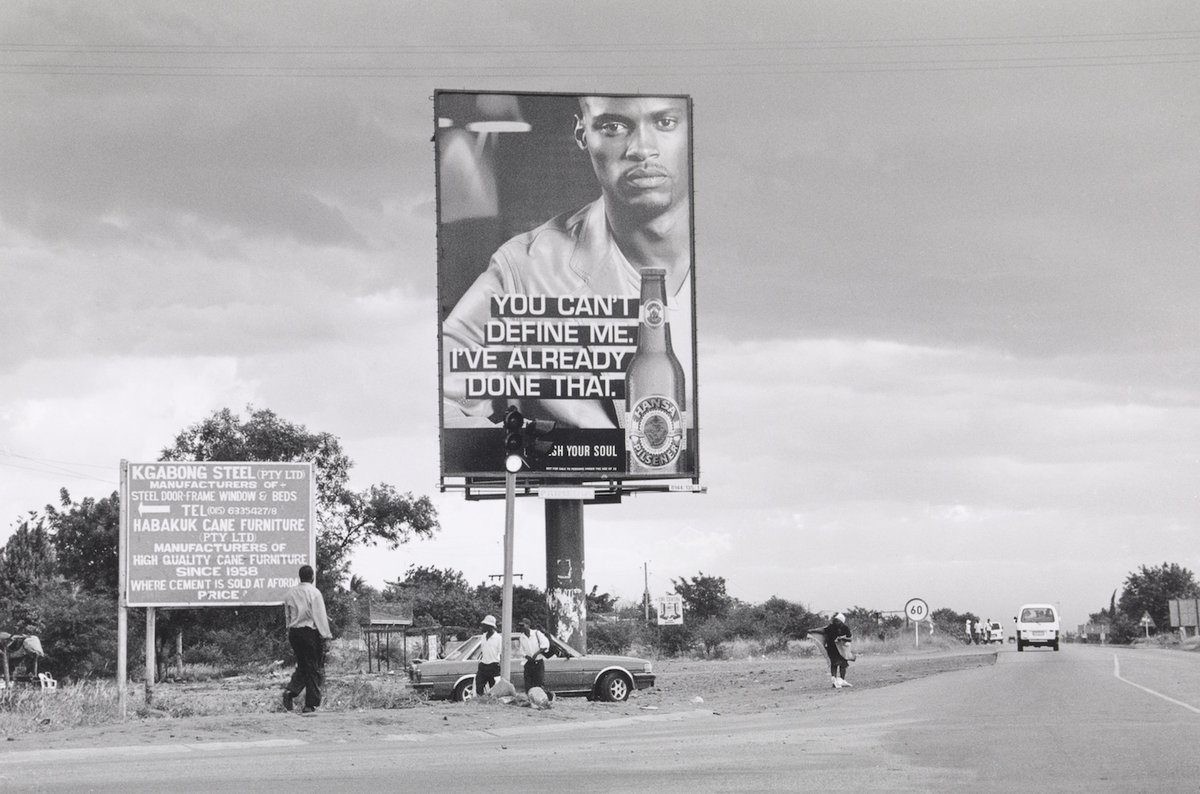

It was through my work as an archival researcher that I would be reminded of the many temporalities in Mofokeng’s work. Two key ‘stories’ featured in the exhibition (WHICH ONE EXACTLY?!) seem indicative of the ways in which Mofokeng moved through the world as a photographer; namely: Train Church – shot in 1986 inside an overcrowded commuter train that ferried Black workers from Soweto to the center of white capital and dominance, Johannesburg city. And the Billboards series, which he produced between 1991 and 2009, documenting the ubiquitous and deeply ironic signs of free-market capitalism that quickly proliferated the township’s landscape in this post-Apartheid period of socio-economic adjustment. The disparate realities depicted in the Billboards series are a lasting reminder of the legacy of Apartheid.

Mofokeng’s archive validates my understanding of the history of South African photography as one that should encompass a multiplicity of perspectives – not limited to the front page conflict ridden news image, which itself is a certain kind of militant visual that was also adopted on an international scale in global media coverage of the country’s violent political turmoil. South African visual history and theory scholar, Patricia Hayes[2], has written extensively on what she terms the ‘photographic estrangement’ evident in Mofokeng’s practice. She argues that in the 1980s in particular the photographer himself was ‘an increasingly important critic of mainstream photojournalism, and of the ways Black South Africans were represented in the bigger international picture economy during the political struggle.’

Indeed, over the years, I’ve noted the ways in which Mofokeng’s work often makes us, the viewers, invariably complicit in our own positionalities – almost as much as he is as a documenter. His work especially challenges us South Africans to be more critical of the way in which we consume images of our difficult histories.

Seeing his photo-essay about a one-night Concert in Sewefontein, I am once again reminded of just how long I have lived with Mofokeng’s work. Sometimes almost unnoticedly it has informed the criticality of my own research practice and reminded me to refuse the oversimplification of what is a complex place in which to live and work. The one image from the series that is as ingrained in my recall as an iconographic piece of art was in danger of becoming flattened in my imagination. In the image a man stares directly at Mofokeng’s lens while standing in the haze of energy and movement that surrounds him. I’d seen the same image reproduced in several key publications that often fell into the trap of historicising South African photography as a singular narrative – a mono-subjectivity ‘captured’ in the frame of the image. For me, Mofokeng’s work disrupts this perception quite pointedly.

Through ongoing conversations with friends in the photography community back home, I continue to contemplate the significance of Mofokeng’s extensive archive and the very precise vocabulary that a current generation of South African photographers has inherited as a contemporary way of looking.”

Thato Mogotsi independent curator based in Johannesburg, South Africa. This statement was initially presented at FOAM Amsterdam, NL during the public event: Soweto Blues – The Instruments of Salvation on 4 April 2019.

[1] From video interview with Santu Mofokeng by Tamar Garb, South Africa, 2010. Originally produced as part of a series for the Figures & Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London UK (12 April – 17 July 2011). Published 5 March 2019.

[2] HAYES P. 2009, Santu Mofokeng, Photographs: The Violence is in the Knowing in History and Theory, Theme Issue 48, p 34 – 51, University of the Western Cape.

Opinion

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

La dignité sous contrainte : la peinture figurative panafricaine au-delà du marché de l’art international

An Exhibition Aims at Accessibility Against a Backdrop of Protest in Kenya’s Capital

Opinion

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

La dignité sous contrainte : la peinture figurative panafricaine au-delà du marché de l’art international