How Tunisians Reclaimed their Capital City with Light Art

10 October 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

7 min de lecture

Connecting contemporary art with architecture, INTERFERENCE is an international light art project in Tunisia that is transforming its capital’s Medina into a center of attraction, even after dawn. This year, the 42 invited artists addressed the theme of cultural heritage in a changing country that is rich in history, writes C&’s deputy editor Will Furtado.

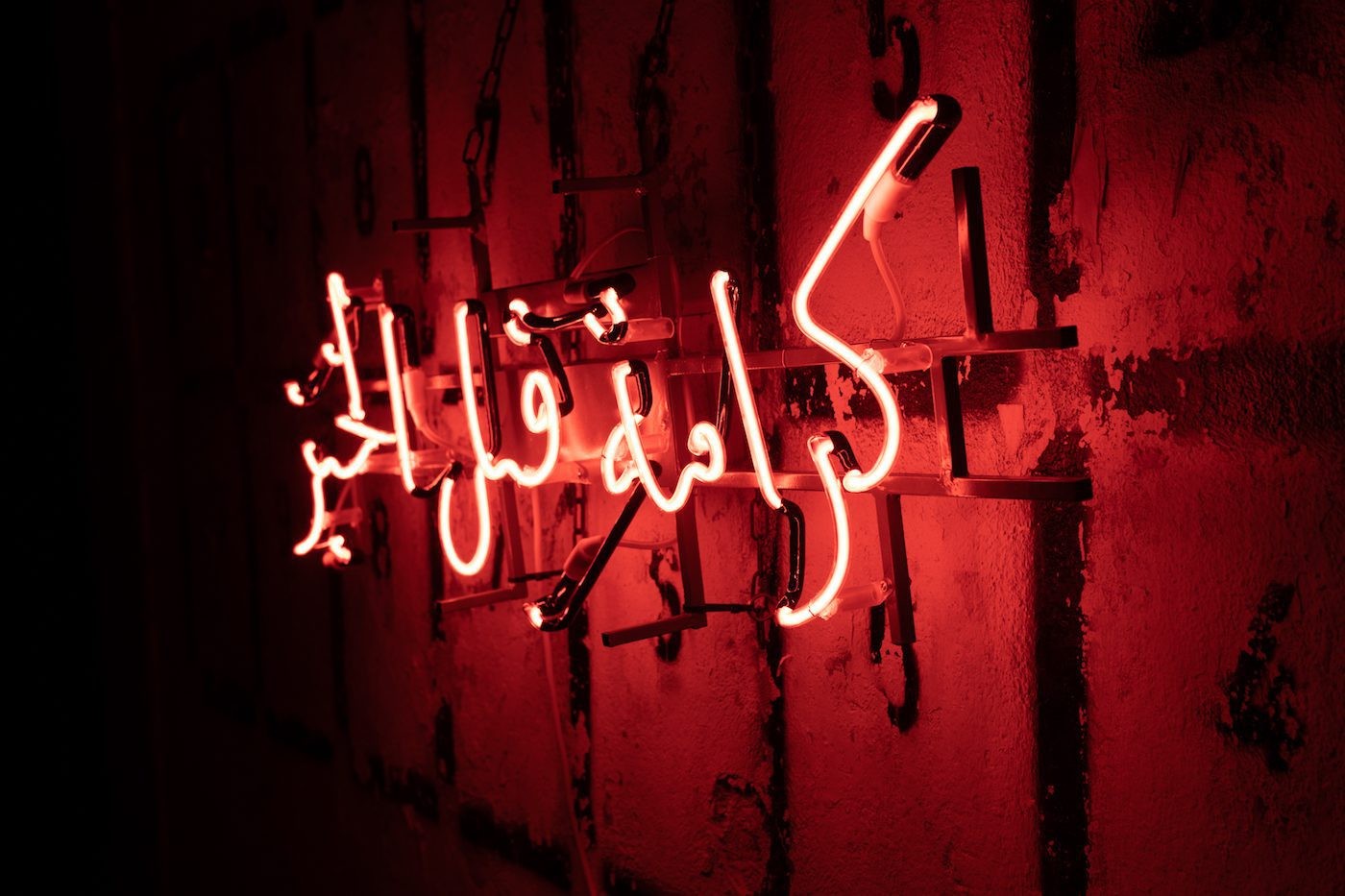

“Dignity Before Bread,” a red neon sign reads in Arabic on a white wall. Made by the artist collective Claire Fontaine, the artwork refers to one of the most popular phrases shouted on the streets of Tunis during the Arab Spring of 2011. Since toppling Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s governance then, Tunisia has enjoyed a new level of freedom, creative or otherwise, that has enabled new initiatives to blossom. One of these is INTERFERENCE, the international light art festival which the collective Claire Fontaine took part in from 6 to 9 September 2018 in the Medina of Tunis.

Featuring 42 international artists, the second edition of the festival had the aim to explore the meaning of cultural heritage and its relationship to contemporary art. The first edition took place in 2016 after Tunisian artistic director Ayman Gharbi met Bettina Pelz, the founder of a similar festival in Germany: Lichtrouten Lüdenscheid. The debut initiative launched by both curators in Tunis proved a unique experience as it was the first light art festival in Africa, but also because it revitalized the rundown Medina which had previously only been busy during the day or during Ramadan. Simultaneously the festival also reclaimed some of the public space which was before only used for transit. “In Tunisia people can now use the public space,” Ayman Gharbi says. “And are free to give their opinion publicly, too.”

</a> Interference 2018. Hartung und Trenz. Photo: Jennifer Braun</figure>

Yet, despite the newfound freedom there are still certain official spaces where for instance photographs are not allowed. So, one of the remarkable achievements of this edition was the projection of an artwork with a political message on the façade of the City Hall just outside the Medina. The project was by the German artist duo Hartung + Trenz and consisted of the projection of excerpts from the new constitution onto the building. The constitution itself was influenced by the South African one and drafted with the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, an entity which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015.

This project also fit in perfectly with the overall theme dealing with “cultural heritage,” an idea which emerged after many artists from the first edition highlighted the incredible 8th century architecture of the Medina, a UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “And we couldn’t talk about architecture without connecting it with the social structure and urban tissue,” explains Gharbi.

This proved to be crucial even with regards to getting some of the permissions (e.g. to project work onto the City Hall and turn off the lights of the Place de la Kasbah) which the curators achieved through a collective effort including the volunteers and their extended networks. With around 200 volunteers, INTERFERENCE plays an important role in engaging with the local youth, many of whom are students, and connecting them to the wider world through their interaction with the invited artists and international visitors.

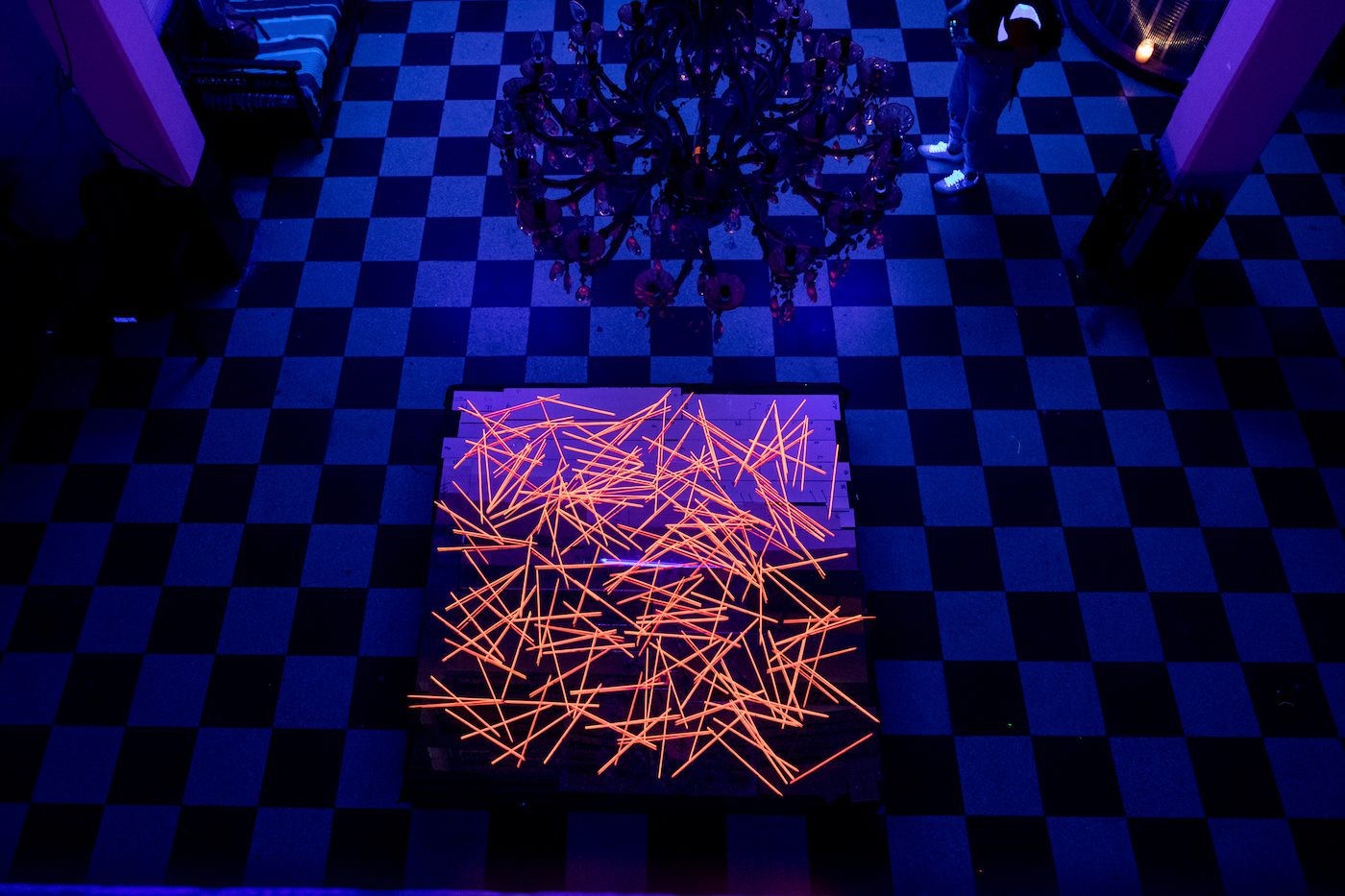

Among the international crop there were also local artists such as Houda Ghorbel + Wadi Mhiri. For this edition of the festival the multidisciplinary artists created a fluorescent installation in two adjacent rooms. The first room was replete with suspended letters from the Arabic alphabet, producing a mesmerizing effect while perhaps alluding to Arabic as a language that is struggling, or as pop culture magazine Mille put it – is no longer “cool”.

Going beyond simple projection, the festival curators invited the artists to use light in all its senses. One particularity of INTERFERENCE is that most of the works are site specific, making the most of the best conserved Islamic architecture of the region. The US artist Andy Behrle, for instance, produced a series of digital recreations of the geometrical patterns of Tunisian tiles and door frames that were then projected onto the inside and outside walls of the Medina.

</a> Interference 2018. Ahla Bik. Photo: Jennifer Braun</figure>

Ahla Bik, the Tunisian collective formed in 2018 by Yasser Jridi and Wahib Chebbi, devised a simple yet visually stimulating installation at Dar Al Jaziri, House of Poetry. Hanging high in the roofless courtyard, the work consisted of a large-scale square lamp perforated with patterns resembling traditional Tunisian designs. Once lit, the gigantic lamp embellished the already decorated walls below in the form of a light stencil, creating a double effect.

Accompanying the light festival there were seminars and presentations dealing with the main theme of cultural heritage and contemporary art from artistic and curatorial perspectives. Some of the questions discussed included who decides what “cultural heritage” is. For these events, non-exhibiting artists were also invited, and perhaps the best defining statement came from Moroccan artist Mohssin Harraki, who claimed that everyone has the right to their own personal cultural heritage. In the closing roundtable discussing Light Art in Africa, the featured guests included Gervais Hugues Ondaye of FESPAM – Festival Panafricain de Musique in Brazzaville, Congo.

</a> Sadika Keskes' project with local women refurbishing the tapestries that influenced Paul Klee.</figure>

Besides the festival, cultural heritage is a topic that remains very relevant to Tunisia. The Maghrebi country boasts several archeological and historical sites from the Roman and Carthaginian empires. Another particularity of Tunisia is its natural light and colors in nature and fabrics which have attracted artists such as Paul Klee, who decided to become an artist after visiting the country in 1914. Klee went on to use some of the patterns and color palette found in the traditional local tapestry in his own art. One hundred years on, some of the actual tapestries that inspired the Swiss artist are being renovated by local women in a project run by Tunisian artist Sadika Keskes, whose work often addresses specific social contexts such as the refugee crisis.

</a> Interference 2018. Marek Radke. Photo: Jennifer Braun</figure>

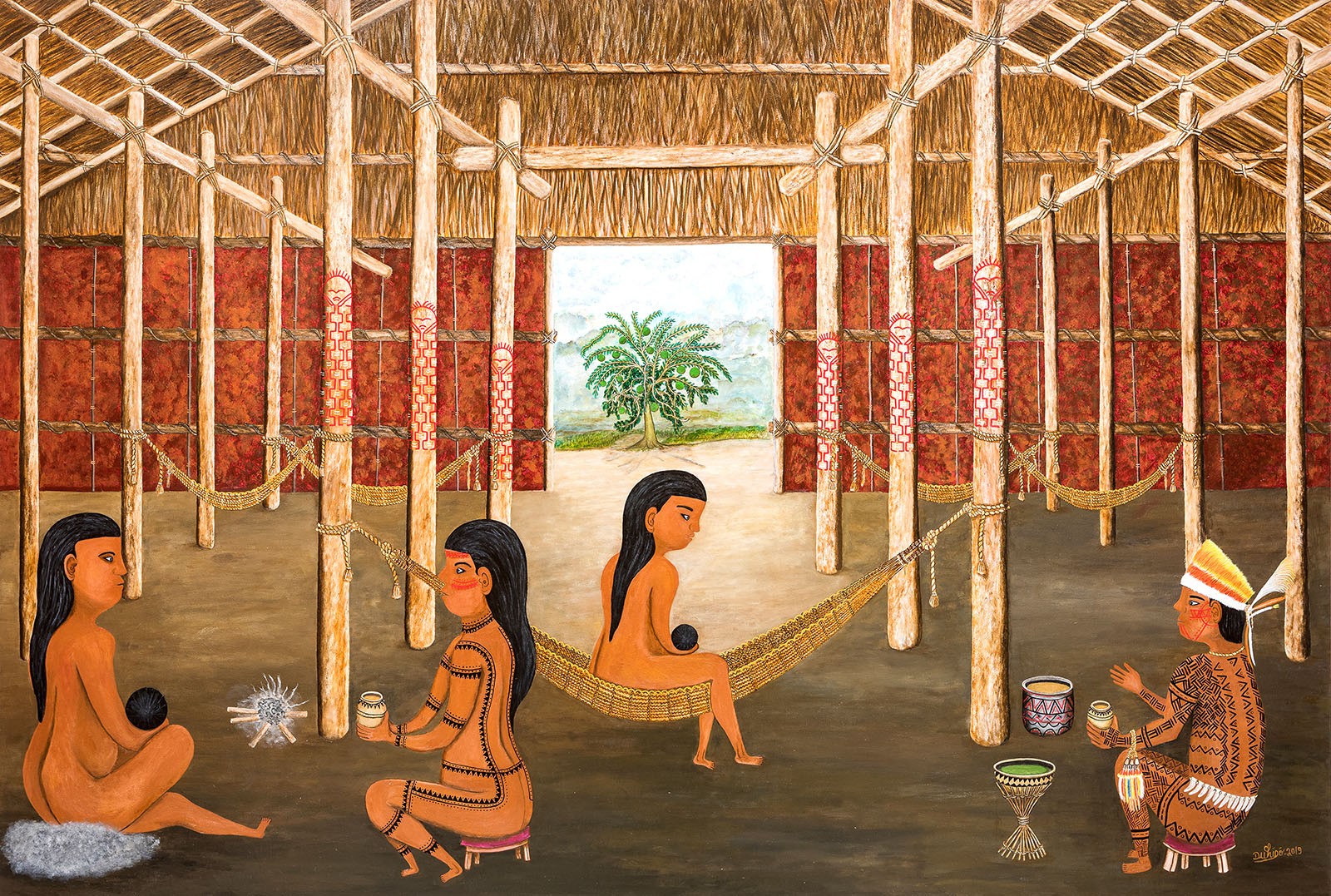

Because of its geographical position in the middle of the North African Mediterranean coast, one cannot talk about Tunisia without mentioning its impeccable and splendid beaches. It was also for this reason that it was important for INTERFERENCE to commission works produced with recycled or upcycled materials. These included Marek Radke’s installation with UV lights at Dar El Jamiet. Another initiative was the decision to refrain from printing any information material but to instead develop an online map for which an internet connection was needed.

Using its own city as a canvas, INTERFERENCE has turned its once neglected and feared nighttime Medina into a place where contemporary art meets architecture and an enthusiastic young local scene. Since its first edition, visitor numbers have double to 20,000 and every night the festival is on, the narrow white streets are brimming with people moving from venue to venue and street vendors. Yet Ayman Gharbi still feels the future of the festival is uncertain due to a lack of funding. “But the volunteers are already really excited about the following festival,” he says. “They keep asking me: ‘So what are we doing for the next one?’” INTERFERENCE took place in Tunis from 6 to 9 September, 2018.

Review by Will Furtado.

Plus d'articles de

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Plus d'articles de

The Spiritual Technologies of Jamaican Maroons

What Needs to be Considered When Running a Museum in (South) Africa?