Giving Birth Being Birthed

08 June 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min de lecture

Dineo Seshee Bopape's complex creativity gives form to a practice that is simultaneously idiosyncratic and richly associative, writes Liese Van Der Watt.

Dineo Seshee Bopape is a South African artist who explores the cultural and personal dimensions of emotion and representation. Although she works with a vast array of media, Bopape is best known for her immersive environments, one of which won her the 2017 Future Generations Art Prize. Her creative process – which is showcased at the 10th Berlin Biennale – is simultaneously idiosyncratic and richly associative.

When Dineo Seshee Bopape speaks, her hands join in the conversation. They seem to punctuate phrases, they complete sentences while her voice trails off, they trace forms and outlines in the air where words seem to fail her, they flutter and feel around for stable ground. It is as if she is searching, constantly, for that which lies beyond language, trying to hold onto a realm which isn’t ordered by syntax and semantics but by an altogether more fluid and nebulous state where meaning is never anchored but endlessly sought for, suspended, and deferred. In an interview Bopape once mentioned that languages “speak her” as much as she speaks them. It was a somewhat offhand comment, perhaps an afterthought, but it provides a subtle yet crucial point of entry into her art, suggesting an idiosyncratic relationship to communication and the act of creating. Take, for instance, the various iterations of what is often inadequately referred to as her “land” or “earth art,” which she has produced over the last few years after moving away from earlier video art and for which she won the Future Generation Art Prize in Venice in 2017.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Mabu, Mubu, Mmu, 2017. Mixed-media installation, variable dimensions, installation view, Future Generation Art Prize. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut. Photo: Pinchuk Art Center

In sa __ ke lerole, (sa lerole ke __) (2016) and Mabu, Mubu, Mmu (Venice, 2017), she fills an empty room with compacted soil, into which she fashions various shallow, round, womb-like holes, sometimes lined with gold leaf, around which are dotted rocks, shells, feathers, healing herbs, and clay forms produced by a clenched fist. Bopape references her biography when she talks about these works, invoking the dry earth of Polokwane, north of Johannesburg, where she grew up, but also the more urgent politics of land and landlessness in her home country. In South Africa, as indeed everywhere else, land is a proxy for many conflicts around race and dispossession, and therefore a site of memory and identity. But it is clear that for Bopape the land or earth is an extension of the gendered self, as if the self is the land, as if the land – like a language – “speaks” the self.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Sedibeng, it comes with the rain, 2016. Mixed media, variable dimensions. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut

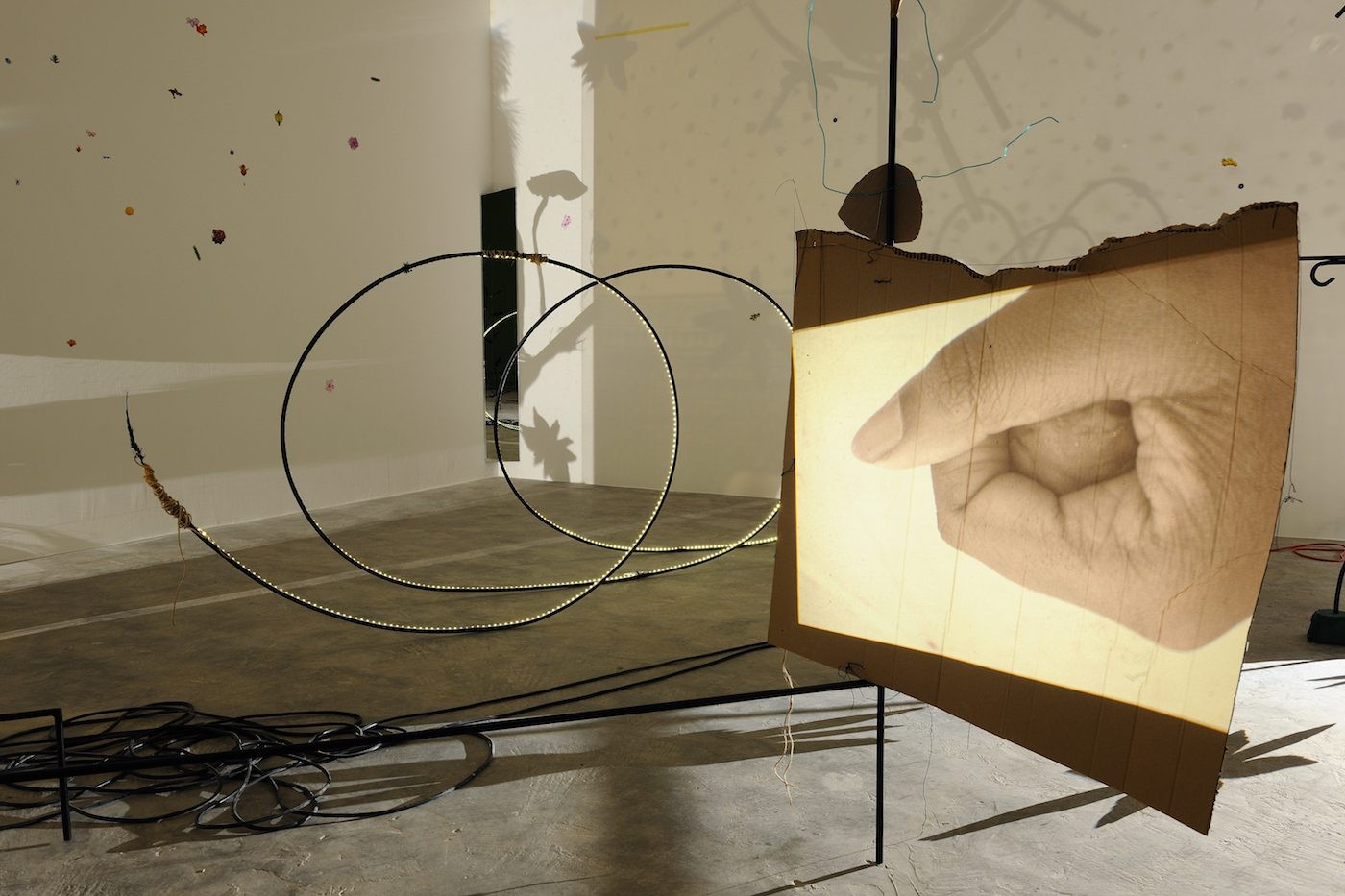

Like the titles of the two above-mentioned works, which both refer to soil and dust as an active and productive substance in Bopape’s native Sepedi language (1) her land works suggest a relationship with the land that is integral, primary, essential. This is crucial: unlike most land art, where the artist creates or fashions or manipulates the land from a Cartesian distance – creating an object to be viewed by the detached eye – it is as if Bopape emerges from the land, as if she is inside the land: the clay formed by a clenched fist emerging from a self in and of the land. In a London talk, Bopape discussed Sedibeng, it comes with the rain (2016), which was acquired at Frieze for Towner Gallery in the UK. The work, as the gallery’s head of exhibitions Brian Cass explained, represents “the edge in landscape.” It is a mixed-media installation with anthropomorphic metal structures and bendy beams, with bags of herbs, feathers, mirrors, and images of fruit and African flowers scattered among the beams. A slide projector shows the clenched fist, moulding and discarding clay shapes. The installation invokes cosmology, fecundity, productivity, and frustration in that ubiquitous fist. It is landscape by association only. “Is Miro an influence?” asked someone in the audience. “Not really,” answered Bopape, somewhat puzzled. Ana Mendieta? “Maybe. A little.”

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Sedibeng, it comes with the rain, 2016. Mixed media, variable dimensions. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut

These are reasonable suggestions, but I realized that something was eluding and probably ensuring the fascination of this largely European audience: it is not only the metaphysical and spiritual practices relating to Africa and its Diaspora that Bopape refers to in this work. There is something much more elementary and intimate at play which has to do with a local tradition of South African sculptors such as Jackson Hlungwani and Samson Mudzunga, who had deep and bonded relationships to the earth from which they fashioned their wooden sculptures, and from which Mudzunga would emerge repeatedly, staging his rebirth. It also has to do with an aesthetic that references the color of South African dust, the bareness of a scrubbed and swept yard around a Limpopo homestead, and with the ordered randomness of ritually significant objects in that land. By this I am not suggesting that there is something essentially “African” in this work and therefore illegible to anyone who is not African; rather I am suggesting that there is an aesthetic and emotional charge in this work that is uniquely located in place and site and in an altered and radically different relation to land and landscape.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Mabu, Mubu, Mmu, 2017. Mixed-media installation, variable dimensions, installation view, Future Generation Art Prize. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut. Photo: Pinchuk Art Center

In Sa koša ke lerole (2016) Bopape explores the history of the Polokwane Choral Society, of which both her parents are members and which has played an integral part in her life. The work may seem surprisingly documentary in an oeuvre so committed to association and intuition, but in fact it circles back to that same concern with rootedness and memory and language. On one level this is a layered history of a communal choir through archival photographs, video, and sound, interviews and various memorabilia. Yet the installation is also a complex journey into memory, interiority, and identity and how this is born from place and history. As much as Bopape creates this work, the choral society also “sings” her into being.

Giving birth. Being birthed. Bopape performs this birth with every creative process anew, giving form to a practice that is simultaneously idiosyncratic, local, and specific, but also richly associative, reaching far into that space beyond words and conventional language.

Dineo Seshee Bopape is a participating artist in the 10th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, taking place from June 9 to September 9, 2018.

Based in London Liese Van Der Watt is a South African art writer and associate editor of C&.

(1) To be precise, sa __ ke lerole, (sa lerole ke __) (“that which is made _ _ _ is made of dust [that which of dust is ___]”) and Mabu, Mubu, Mmu are all variants of the word for soil.

This essay was initially published in our new C& Print Issue #9. You can read the full magazin here.

Plus d'articles de

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Plus d'articles de

MAM São Paulo anuncia Diane Lima como curadora do 39º Panorama da Arte Brasileira

Naomi Beckwith présente l’équipe artistique qui l’accompagnera pour la documenta 16