Disturbing memory

05 February 2015

Magazine C& Magazine

4 min de lecture

C&: During the Dakar Biennale earlier this year, you received the Fresnoy Studio National des Arts Contemporains prize in Tourcoing, France. What will this mean? Nomusa Makhubu: This prize sponsors a residency at the prestigious post-graduate research facility Le Fresnoy. It has come as a blessing because it is not always easy to find the right resources, space …

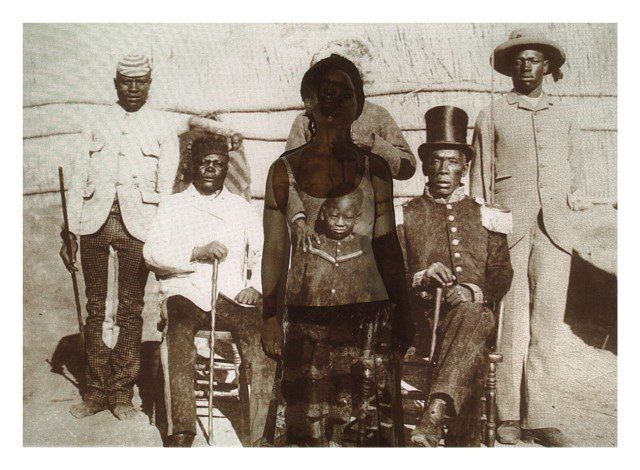

C&: During the Dakar Biennale earlier this year, you received theFresnoy Studio National des Arts Contemporains prize in Tourcoing, France. What will this mean? Nomusa Makhubu: This prize sponsors a residency at the prestigious post-graduate research facility Le Fresnoy. It has come as a blessing because it is not always easy to find the right resources, space and time to make artwork. I recently completed a PhD in Art History and Visual Culture at Rhodes University in South Africa, so I work both as an artist and an art historian. Balancing the two can be tricky. I hope this prize will allow me more time to focus on making art. C&: Could you talk a bit aboutthe award-winning series of photographs that were shown in the international exhibition “Producing the Common” at Dak'Art 2014. NM: These are historical photographic portraits of women in southern and eastern Africa published in Michael Stevenson and Michael Graham-Stewart's book Surviving the Lens: photographic studies of South and East African people, 1870-1920 (2001). During this series, I projected existing photographs into new spaces in order to interject the visual language of past prejudice with the stark visual language of contemporary presence. C&: How did this series come about? NM: The Self-Portrait series was originally part of a body of work and an exhibition called Pre-Served, which focused on representations of African women in colonial photography. This project represented a few challenges: the photographs themselves were problematic because they set up a clear distinction between the photographer and the photographed as male and female, European/ African, white/black – in which the former is always privileged. I wanted explore ways in which it might be possible to subvert that hierarchy, and re-write the political implications in the photograph. I asked: of what use are these photographs to contemporary politics? Of what use are tools of memory if they serve a denigrating history? Since they represent colonialism, should they simply not be erased from memory, forgotten, and delegitimized? The women in the photographs that I selected had come to represent collectivities of women and men who have been subjected to the dehumanizing scientific gaze. C&: Importantly, the titles of these self-portraits are in Zulu, with English translations in brackets. NM: Indeed. Titles like Mfundo, Impahla neBhayibheli [Education, Apparel, and the Bible], (2007/ 2013), Umasifanisane [Comparison] (2007/2013), and Goduka [Going/ Migrant Labourers] (2013) disturb the meta-narrative. I grew up in the industrial southern parts of Gauteng, in the Vaal Triangle, which was more socio-linguistically “mixed” by comparison to areas that were in former bantustans. I realised that when one is searching for one’s so-called identity, one begins with cultures attributed to socio-linguistic groups. I was looking for Swazi culture but I speak Zulu and thought I was Zulu. I spoke Sotho as well, having learnt it from other children around me. This project made me realise how problematic it is to consider socio-linguistic groups as autonomous cultures. I use performative photography to revise the ways in which post-memory is not only inherited memory without primary experience, but can rupture and interrogate predominantly masculine historical narratives. Performed photography, in which the archive or historical as well as canonical photographic imagery is appropriated, functions as a necessary interruption and a powerful assertion. C&: Can you tell us about your on-going research in Lagos? NM: In brief, I spent time in Lagos in 2010 and 2011, and I have been studying Nollywood film. Since my first trip as a fellow ofthe Omooba Yemisi Adedoyin Shyllon Art Foundation, I became aware of what a wealth of art and culture Nigeria has. I plan to continue to research there. C&: What exhibitions you are currently working on? NM: I have recently shown work in theABSA L'Atelier “Blood, Sweat and Tears”exhibition at the ABSA gallery in Johannesburg; and “Silk and Steel” at Gallery Noko and the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Art Museum Biennale in Port Elizabeth. My work is included in the current exhibition entitled “Am I Not a Man and a Brother? Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” which is a group exhibition at the Archer Gallery, Clark College, Washington. I have also been working on an exhibition of photographic works entitled “Lagosian” based on work I made in Lagos, Nigeria, in 2011. Caroline Hancock is an independent curator, writer and editor based in Paris.

Plus d'articles de