Design Your Own Daddy

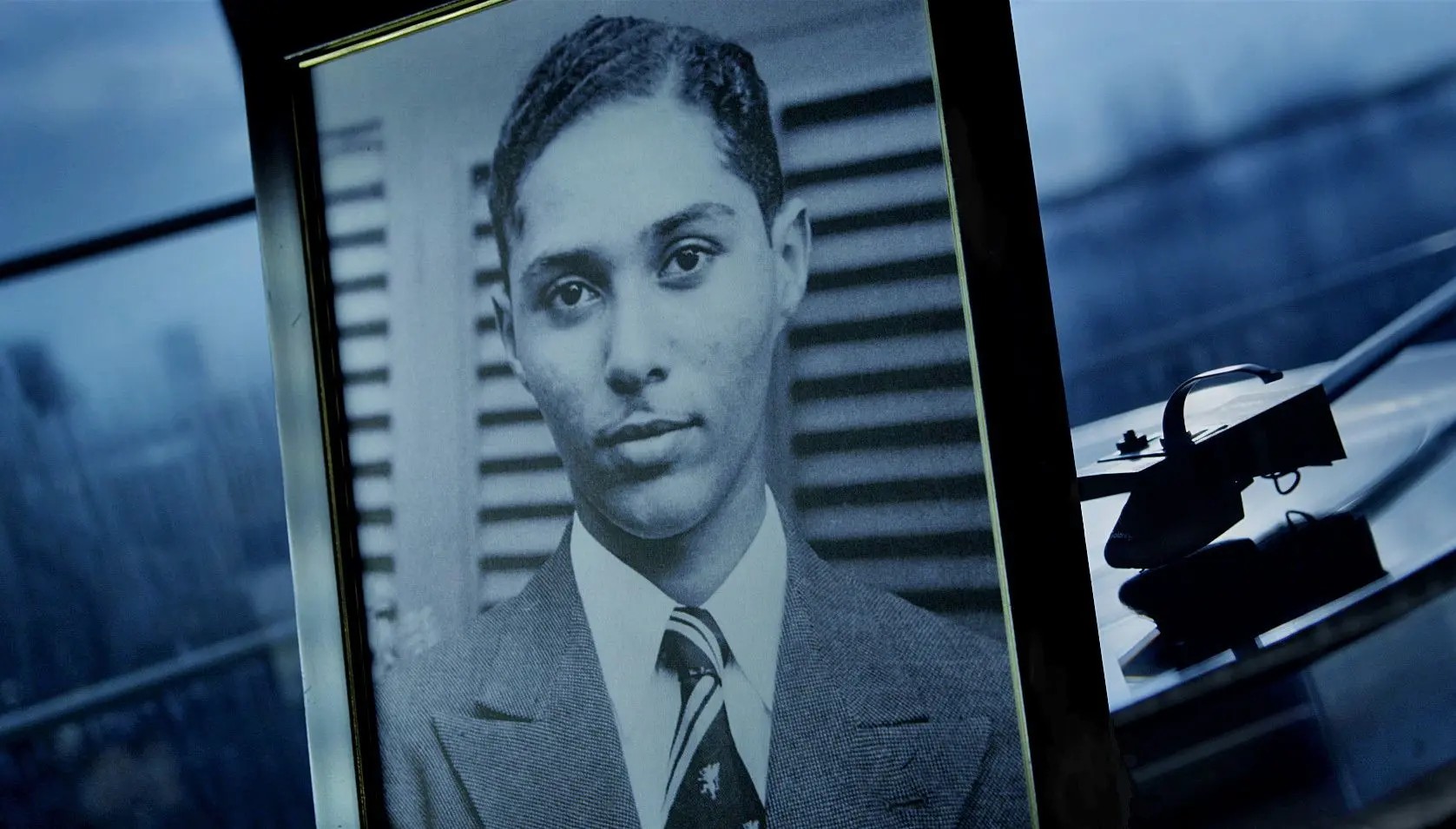

A conversation about father figures and artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode...

Cultures have constructed a wide array of attributes around the figure of the father. But now fathers are taken to pieces in a Berlin exhibition called“Father Figures Are Hard To Find”. A group of five curators – Alicia Agustín, Raoul Klooker, Markues, Tucké Royale and Vince Tillotson – challenges normative narratives and seeks for alternative role models. Magnus Rosengarten spoke to them

Magnus Rosengarten: Why “fathers” and why now?

Alicia Agustín: This figure is such a mythological and psychoanalytical thing in itself. Look at the beginnings of democracy in Greece, which destroyed a lot of the old, ancient matriarch ways. Suddenly it was all about the father, the man. Can it really be that in 2016 we are still there? Also, the whitewashing of art is becoming a topic again. For us it was important to show People of Color as possible father figures too.

Markues: When you are queer you also want genealogy. We try to acknowledge those emotional needs and want to address them.

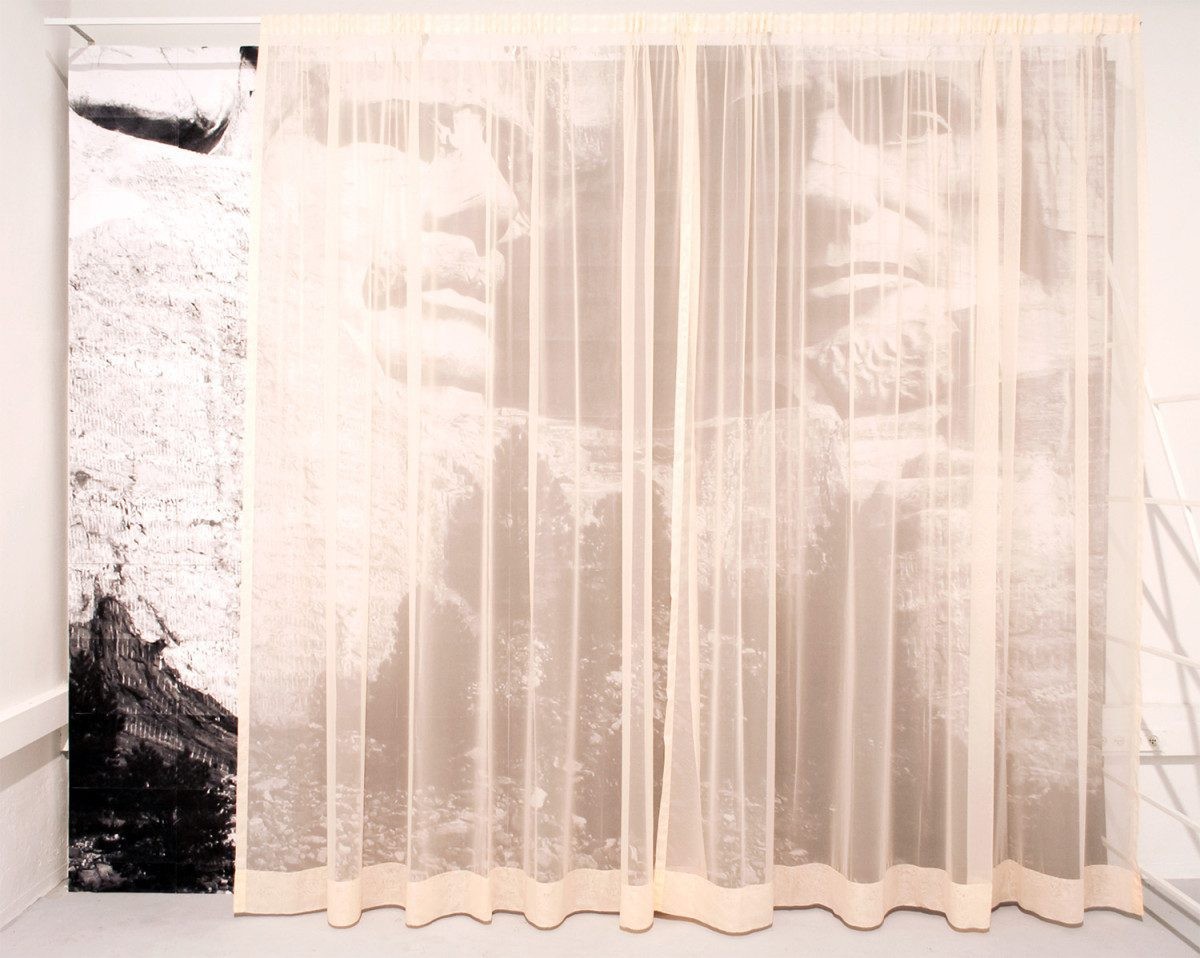

Naama Arad, Har-Hazofim, 2010 © Photo: Barak Zemer

MR: How did you approach the curating process?

Raoul Klooker: We had an open-end, associative approach. We met up weekly and discussed different ways and angles on the topic. For example we would talk about the concept of a “sugar daddy” and ask ourselves, what could symbolize a father?

Alicia Agustín: I think a lot of private stories came out. Wounds opened and closed and opened again. We are extremely involved as curators. Everyone has an object of our actual fathers in the exhibition too. But we will not reveal which one belongs to whom. It is very personal. The exhibition is built in this labyrinth way, so you can always feel the constant seek for the father figure. There are so many narratives around it. It is a whole journey and we wanted the viewers to encounter different approaches. At some point we describe the search as a kind of buffet where you can choose and maybe find a new father figure, so you don’t have to suffer a potentially absent one. It is about the queering of all of that.

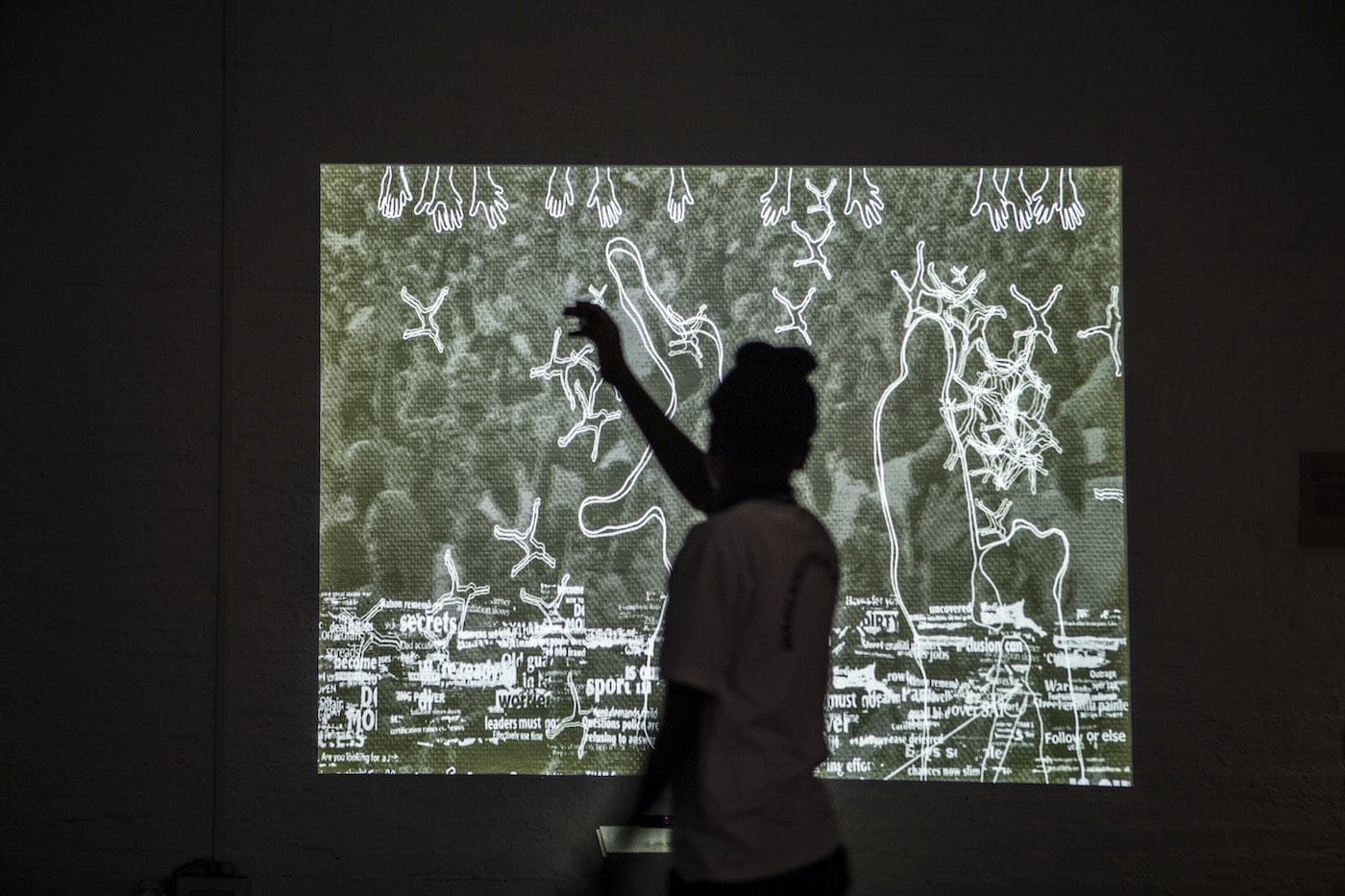

Raoul Klooker: Also, when you look at the lighting, it is not a neon-lit white cube space. The lighting is actually very theatrical, it creates an installation as a whole. It doesn’t just create an assemblage of positions in a white space.

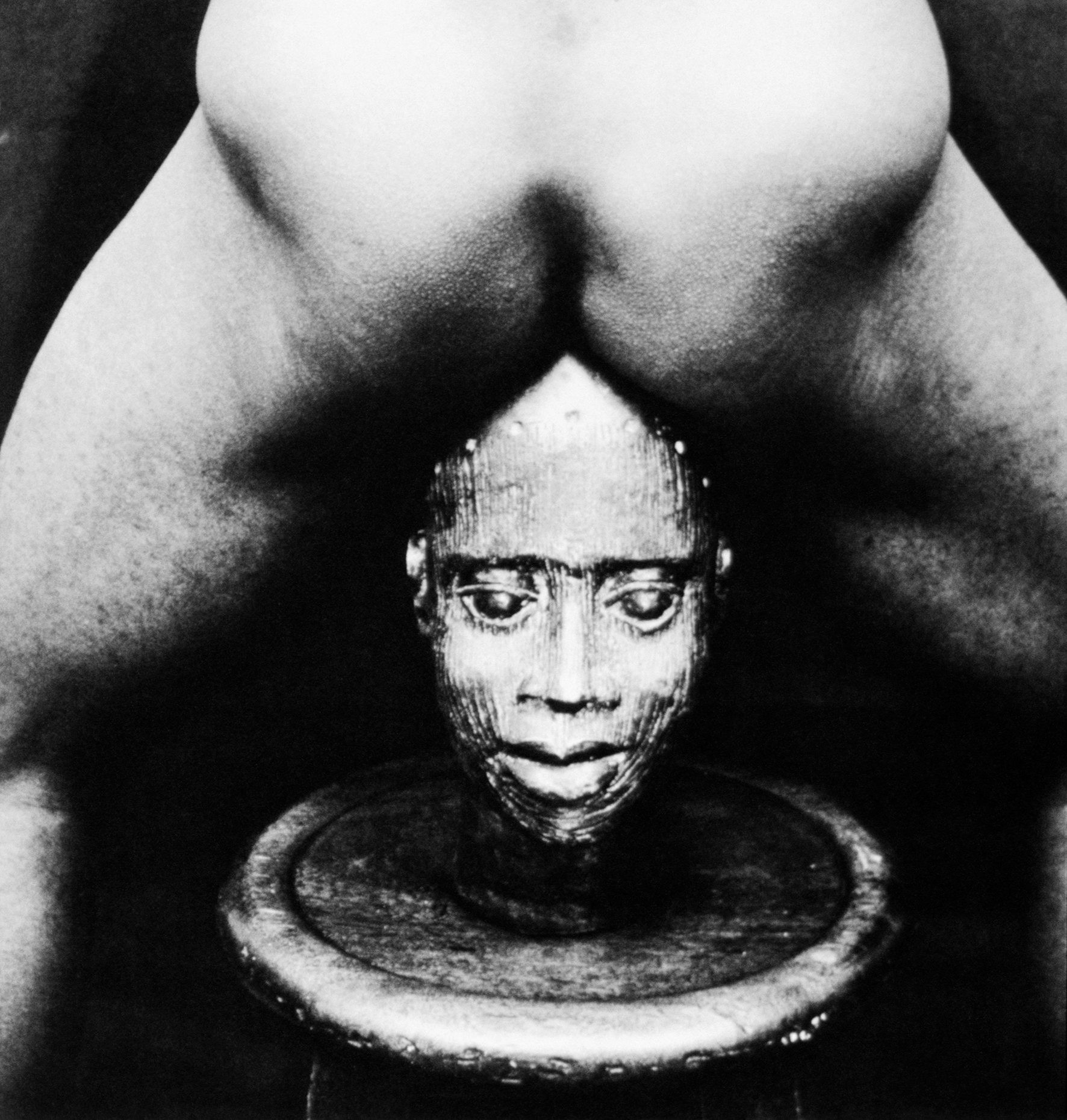

Rotimi Fani-Kayod, Under the Surplice, 1987 © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph ABP

MR: One specific segment of the exhibition deals with spirituality. Rotimi Fani Kayode’s photographs are particularly invested in topics around transcendence, ritual and sexuality. How would you contextualize his photographs with the other artists’ works shown in his section?

Markues + Raoul Klooker: We put Rotimi’s photographs together with Heike-Karin Föll´s plant drawings and two saint figures of Michaela Meise. Often Rotimi’s work is shown (if at all in Germany) within the context of “African art” which overlooks his critique of western concepts of authenthicity and belonging. At the same time his affirmative politics of spirituality are not traditional in the way that neo-traditional African art relates to religion. But they show a similar longing for chosen kinship as we can see in Heike`s “Kafka`s Gymnastics”. Michaela’s saints of the “Mare Nostrum” series mirror his affirmative and at once critical approach towards spirituality.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Bronze Head, 1987 © Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Courtesy of Autograph ABP

.

MR: What made you choose his work for “Father Figures” ?

Markues: Our project sets off with the thesis that only very few can develop an identity without any authority or guidance. So we were seeking for (queer) forms of reclaiming spirituality as something positive. What makes his work strong in my opinion – and him a potential father figure – is his ability to destabilize and affirm at the same time. He is never cynical or just repeating shallow gestures of rejection. You can find an honest search for spirituality and references to religious Yoruba iconographies in his photos. Interestingly, they combine that with a western subcultural gay aesthetic, so they become legible in multiple ways.

Raoul Klooker: I also admire him for his critical engagement with the ‘Fathers’ of modern art, who dabbled in Primitivism at the beginning of the 20th century. Artists like Picasso used decontextualized stolen artifacts from Africa to answer questions that occurred in European art at the time. They didn’t care about the cultural and ritualistic contexts that these masks were embedded in before being presented as sculptures in Europe. Rotimi engages with “Ifa Bronze” heads and masks in his photos by performing sexualized rituals with them. One photo called ‘Bronze Head’ looks like an ethnological museum photo, which is no coincidence. There is this very graphic anal sex element that can be read as a ‘fuck you’ towards the ways in which looted African Art is presented and appropriated in Europe. But it does make a reference to Yoruba iconographies and therefore tries not just to get rid of tradition but to look for alternative, more inclusive ones.

Markues:..and joyful ones

Raoul:…and sexy ones

Magnus Rosengartenis a filmmaker, journalist and writer from Germany. He lives in New York City and currently works towards his M.A. in Performance Studies at NYU.

Fonction

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room : annotations sur l’art, le design et les savoirs diasporiques

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

In Conversation with Lubaina Himid: The Artist Set to Represent the UK at Venice Biennale 2026