Wendimagegn Belete

Wendimagegn Belete

Closes: 9 July 2022

How can we understand the present without first understanding the past? This question sits at the heart of Ethiopian artist Wendimagegn Belete’s practice. Combining carefully selected archival materials with a more spontaneous, instinctive approach to mark-making, he creates richly textured surfaces that transcend boundaries of culture, place, and time to offer new ways of making sense of our heritage and experiences. For his latest solo exhibition, Codeswitch, at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, London Bridge, Belete continues his explorations into history, and the concept of epigenetic inheritance – of memories that transfer over generations and permeate our present – by focusing, primarily, on the politics of mark-making, in relation to art, but also to the body and landscape. Incorporating different types of map or coding systems, these vivid, layered works invite us to consider how non-lingual modes of communication have not only historically shaped our perceptions of history, but how they might also open up routes for connection.

The exhibition’s title refers to the act of ‘code-switching’, the ability to switch between two or more languages, or dialects within a conversation, especially in response to a change in social context. By using a collage technique to incorporate different artistic materials and cultural references onto a single surface, Belete enacts a form of visual code-switching that not only embraces plurality but also freedom of expression. Over the course of his career, he has built up a vast archive of materials relating to Ethiopian history with a particular focus on the Italo-Ethiopian wars during which Italy attempted, unsuccessfully, to colonise Ethiopia. During this time, the Italians created maps of what they imagined Ethiopia to look like under their rule. These ‘failed maps’, as Belete calls them, formed the starting point for this latest series of works, both conceptually and materially. The artist has silkscreen printed images of the maps onto his canvases, creating a kind of base layer onto which he added fragments of text, paint, pastels, stitching and further prints of ethnographic photographs.

While Belete has used similar imagery in his work before – specifically for his series Your Gaze Makes Me which reappropriated and hand-colourised archival photography to examine issues of ownership and the framing of history –, for this new body of work, he has selected photographs that detail the indigenous ritual of etching signs and symbols into the body using a sharp object. These marks create visible scarring in a specific pattern, or code that might convey a cultural or spiritual, denote status within the community or simply, provide a form of bodily decoration. In a sense, they map out stories onto the contours of the body just as the imagined maps made by the Italians recount the story of colonisation. The way that we perceive and understand these different forms of mark-making, however, is very different. ‘The colonial maps were used to lay claims to the land, they were designed to separate and to create distance, while the scars on individuals’ bodies offer a form of storytelling that is both very direct and very personal,’ says Belete. By combining the maps and the portraits on the same plane, he draws our attention to these differences while also setting up a dialogue that not only questions the intentions behind the marks we make but also how they shape our understanding of the world.

The artist explored similar issues through a monumental mural that he created for the Future Generation Art Prize. The mural, like the artworks in this latest series, brought together portraits of individuals from a diverse range of ethnic groups from across Ethiopia and Western Africa in order to convey a powerful message of strength and unity that challenges Western understandings of ethnicity, which traditionally focus on differences in identity. This perception of difference is what, historically, allowed Western dominating powers to colonise communities and what continues to create cultural divisions across the globe. By employing a collage technique to stitch together a diverse range of materials and references, Belete seeks, instead, to offer a more fluid approach to understanding history and identity. This is also reflected in the medium and scale of the work. By combining printed digital imagery with more physical marks created in paint, Belete complicates our perception of materiality. Meanwhile, the large scale of the work creates a strong bodily presence that makes the viewer acutely aware of their own body in space.

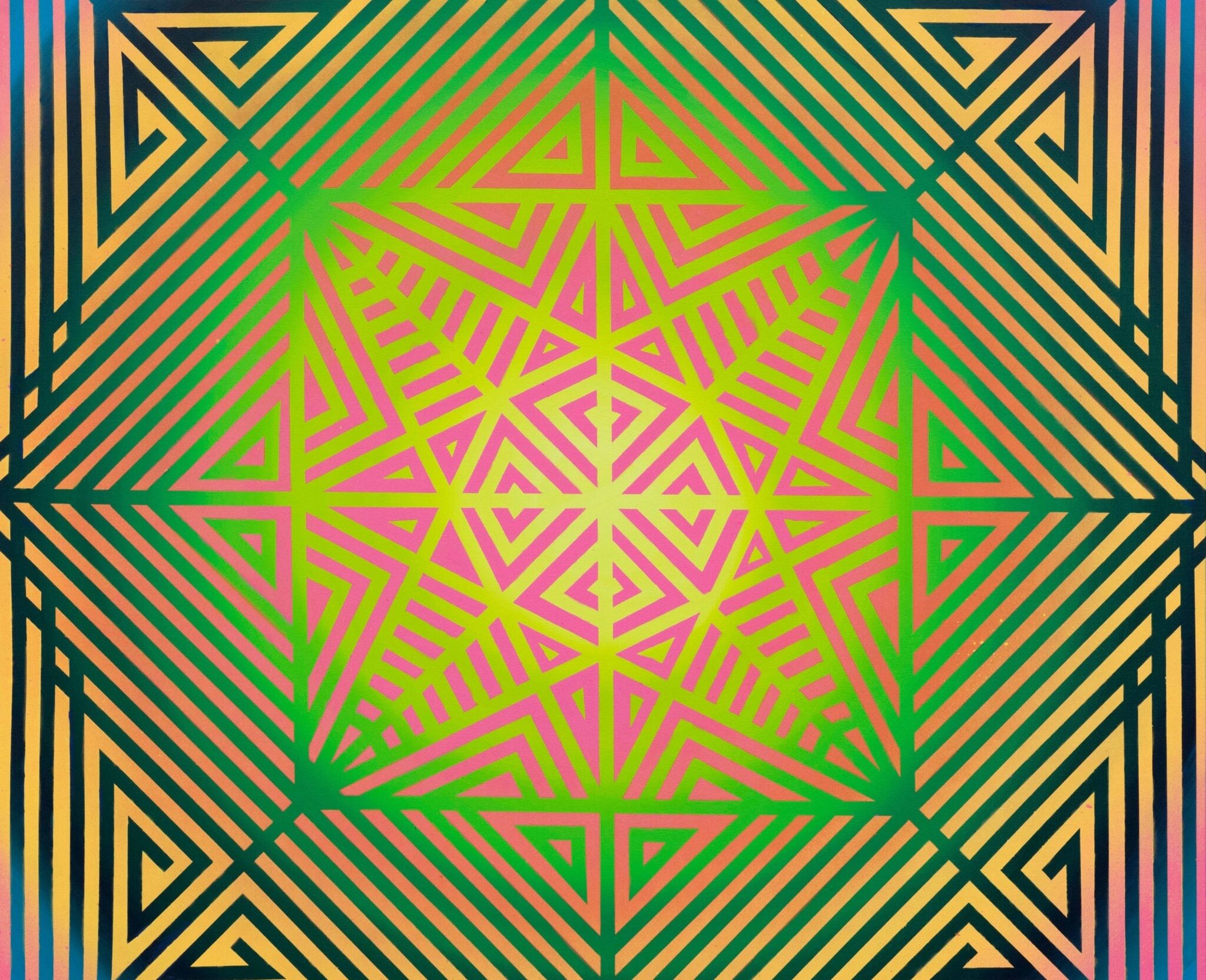

Interestingly, these latest works also introduce a new element to Belete’s visual practice: brightly coloured, geometric patterns that sometimes line the edge of the canvas and at others, cut through the printed imagery. These marks were first inspired by the artist’s encounter of colour blocks that often appear next to black and white archival photographs as a kind of code indicating how the scene may have looked. However, Belete has manipulated their structure to create futuristic, psychedelic shapes in fervent hues that refer, instead, to African textiles, climate and culture. In this way, Belete not just reclaims the images that have been captured by the Western gaze and shaped by a very specific moment in history, he sets them free: allowing us, as viewers, to consider the work without preconceptions, to find meaning that is rooted in the self, our bodies, and our shared experiences.

View more from

Beyond Representation

Cecilia Vicuña - The vanished glacier

Apr 30–Sep 20, 2026

Tierras reimaginadas: migración

La Chola Poblete: Pop andino

Mar 6–Aug 2, 2026

Sophie Rivera: Double Exposures

Apr 23–Aug 2, 2026