The Artists Forging Ecological Ties in Female Fugivity and Marronage

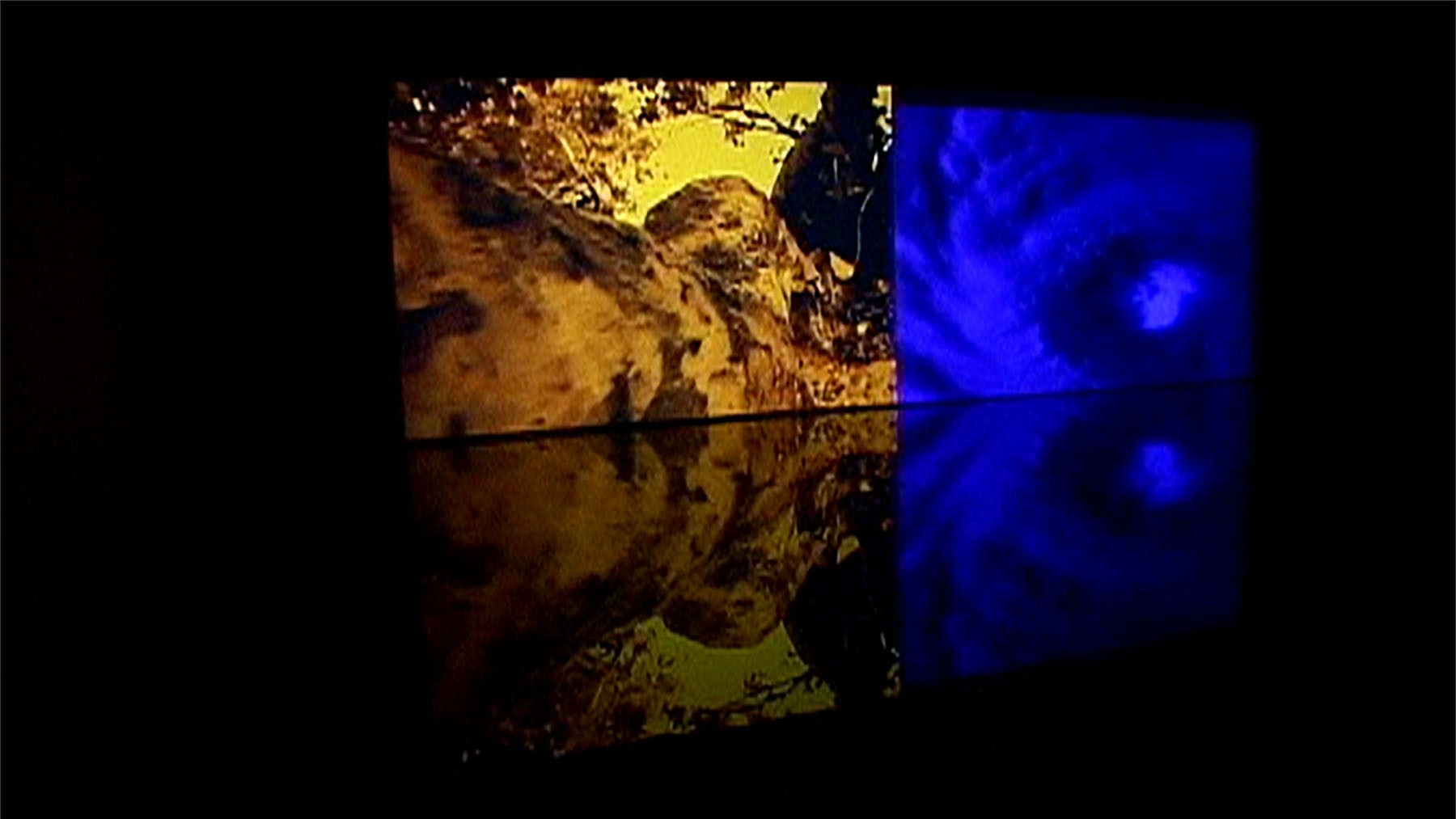

Deborah Jack, the water between us remembers, so we carry this history on our skins, long for a sea-bath and hope that the salt will heal what ails us, 2018. Single-channel color video, 15 min, 42 sec. Courtesy of the Artist.

Juana Valdés, Deborah Jack, and Jamilah Sabur reinterpret the Caribbean as sites of ecological memory and resistance. Valdés explores migration and Afro-Cuban identity through water as a metaphor for dislocation and healing, while Jack uses salt to evoke the sea as a witness to climate trauma; and Sabur draws on geology and language to excavate submerged Black and Indigenous histories, framing marronage as both physical flight and temporal transformation.

For centuries, the Caribbean’s landscapes—mangroves, mountains, caves, and waterways—were sanctuaries for maroon communities seeking freedom beyond colonial rule. Today, Caribbean women artists reimagine these spaces as sites of fugitivity and possibility, engaging shifting ecologies as grounds for autonomy, memory, and speculative futures.

Across Indigenous and Afro-diasporic societies, women have long served as key guardians of sustainable agriculture, medicinal plant knowledge, and resource management, skills vital to community resilience. Despite colonization and patriarchy, this expertise has been preserved and passed down through oral traditions, casual apprenticeships, and sacred ritual. Juana Valdés is a Cuban-born and U.S.-raised artist who explores migration, race, and colonial legacies through materiality, centering women as ecological knowledge keepers and stewards. Her sculptural installation The Journey Within (2003) features roughly 100 delicate, white porcelain boats shaped like folded paper hats. Arranged in clusters to resemble a flotilla, the boats evoked a collective displacement, their fragile forms mirroring thevulnerable state of those undertaking perilous journeys across oceans and seas. The work’stitle, however, posits migration as not only a physical crossing but also a profound internal transformation.

Juana Valdes, The Journey Within, 2003. Ceramic (porcelain cast boats). Dimensions variable, 2 x 3 x 5in. each (100 in set). Photo: Zachary Balber.

Juana Valdes, Otra vez al mar (Farewell to the Sea), 1994. Mixed media (Organza dress, light, fishing net, hooks lead, and audio), 72 x 96 x 72 in. Photo: Zachary Balber

Similarly, St. Maarten-born Deborah Jack envisions the sea as both witness and agent in islanders’ survival, using multimedia installations to consider the impacts of slavery, hurricanes, and ecological vulnerability. In her floor installation shore (2018), Jack immerses viewers in a post-hurricane landscape, employing salt from historic pans, the presence of which serves a dual purpose: referencing both the island’s colonial past, when salt production was a key industry tied to exploitation and trade, and highlighting the ongoing vulnerability of Caribbean shorelines to hurricanes. In her sound work the water between us remembers... (2016), Deborah Jack returns to the sea as source material, using recordings of waves and storms to evoke diaspora feelings experienced by people separated from their homelands by the very bodies of water that once transported them.

As the ocean carries collective memory, Caribbean landscapes also preserve embodied knowledge, much of it rooted in women’s healing traditions. The plantation economies that relied on forced cultivation, reshaped ecologies and subjected Black women to harsh labor and surveillance. Yet women’s botanical and healing knowledge became crucial tools for marronage and subtle resistance. Both Valdés and Jack reclaim these histories, transforming the landscape from a site of extraction into a living counter-archive, where plants, salt, and sediment become witnesses and collaborators.

Deborah Jack, shore, 2004. Three-channel videoInstallation view of "shore" at Big Orbit Gallery in Buffalo, New York. The space was filled with 5 tons of Rock salt, and a 40 x 20 footreflecting pool. The piece makes visual references to Atlantic Hurricanes, Slavery, the Sea. These are connected by assault as a catalyst for historical trauma. It sees the hurricane as a natural memorial for bodies lost at sea during the Middle Passage. Courtesy of the Artist.

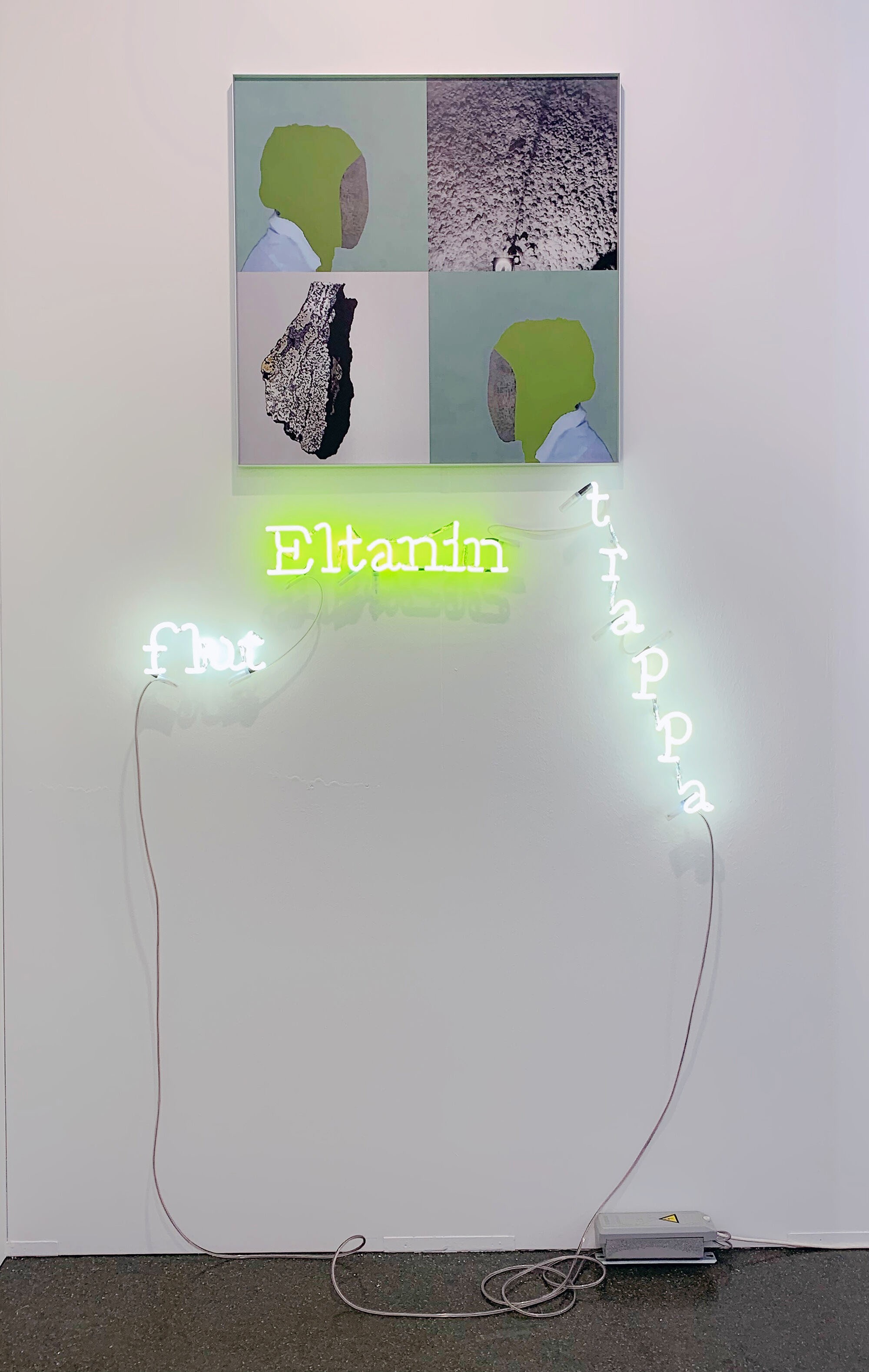

Jamaican artist Jamilah Sabur engages with geology as metaphor and method to access submerged histories and imagine new forms of belonging. Her practice traverses performance, installation, video, and text, drawing connections between the ocean floor, outer space, and Black Caribbean women’s experiences. Sabur’s fascination with geological forms (escarpments, basins, and volcanic rocks among others) is articulated throughout her Hammer Projects exhibition at L.A.’s Hammer Museum (2019), where the escarpment becomes a metaphor for origin and stratified history. Sabur draws attention to how the earth’s surface holds traces of time, movement, and transformation, particularly human histories, shaped by migration, trauma, and resilience. The layers of rock in an escarpment mirror layers of memory, suggesting that our personal and collective origins are built up over time, shaped by both visible and hidden forces. This engagement with geological time frames marronage as an ongoing, seismic process, of upheaval and creation, metaphorized by the shifting earth itself.

Sabur’s work is also deeply invested in the politics of naming and language, an extension of her attention to deep time. During a residency at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum in St. Augustine, Florida, Sabur studied the extinct Timucua language, which she encountered through 1612 Franciscan texts. When she became a U.S. citizen, Sabur changed her middle name to Ibine-Ela-Acu, meaning “Water Sun Moon” in Timucua, a gesture of remembrance and refusal in the face of settler erasure.

Jamilah Sabur, an antipode, a stairway, a spectral standard from Arabic At-Tinnin, 2023. Neon and aluminium tray framed ink jet print, 86 x 86 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and Copperfield, London.

Jamilah Sabur, Un chemin escarpé (A steep path), 2018. Five-channel video installation, color, sound, 11:38. Installation view from the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane, 2019.

The Caribbean’s ecological vulnerability, rooted in centuries of colonial extraction and now exacerbated by climate change, endangers not only its fragile landscapes, but also the region’s rich cultural memory and enduring histories of resistance. The widespread deforestation and soil depletion caused by colonial-era sugar plantations have left many islands susceptible to erosion and hurricane damage, while also erasing traditional land-use practices and Indigenous ecological knowledge. On islands such as Martinique and Guadeloupe, lingering contamination from colonial-era pesticides such as chlordecone continues to poison the land and disrupt local agriculture, undermining both food security and ancestral farming traditions. At its very shores, rising sea levels and increasingly severe storms threaten to submerge coastal heritage sites and ancestral burial grounds, putting tangible markers of Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous life at risk.

Artists such as Deborah Jack, Jamilah Sabur, and Juana Valdes respond to the vulnerability of the region by creating work that disrupts colonial and linear narratives, presenting the Caribbean as a dynamic space of negotiation - where memory and relation become strategies for transformation amid ongoing ecological and historical uncertainty.

About the author

Lauren Baccus

Lauren Baccus is a writer, educator, and independent researcher whose work explores the construction of Caribbean identity through textile, craft, and material culture. She was a participant of the CCI x C& Critical Writing Workshop.

Review

C&AL’s Highlights of 2025 You Might Have Missed

2025 in Review

Macuxi Jaider Esbell: An Indigenous Life Cut Short by Epistemic Extractivism

Review

C&AL’s Highlights of 2025 You Might Have Missed

2025 in Review