Caribbean Sounds: The Connective Possibilities of Radio

Kenny Cairo, Urgence (Urgency), Cité internationale des arts © Kenny Cairo

In a series of non-linear entries, writer Kenny Cairo rewires the sonics of radio and connectivity, from Guadeloupe to Jamaica to Paris.

In September 2024, I began a research-creation residency at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris. I developed the sound installation Urgence, assembled as an orchestra of second-hand loudspeakers. Activated as part of a performance curated by Fondation H, each loudspeaker broadcast sound autonomously, drawing the audience into a sound space saturated with information. At the heart of this performance, one sound-emitting object held a central place: the radio.

Elevated to the status of an active work within Urgence, the radio embodies, in the insular Caribbean context, the possibilities of flight towards Elsewhere through sound and of exploration from the listening site. It also remains a tool for reconnecting Antillean realities through a broadcast that abolishes the archipelago’s maritime borders. This reflection stems from a listening experience within the Guadeloupean landscape, and notably informed my work at the Cité internationale des arts.

Hubert Petit-Phar, Outre-rage (Out-Rage), La Maison Rouge © Kenny Cairo

A Flight Towards the Elsewhere

Hurricanes crossing the Caribbean basin from June to November each year, along with seismic and volcanic activity: such potentially catastrophic natural phenomena are part of everyday life in Guadeloupe. In these situations, radio is the perfect tool for staying informed via the airwaves, on devices that can run without mains electricity and rely on batteries. In Guadeloupe, the population is strongly attached to this object. From January to June 2024, 73% of those aged 13 and over listened to radio (Médiamétrie, 3 July 2024). This listening can be understood contextually: ‘the majority of people in Guadeloupe travel to their place of work by car (84%), and many of them listen to the radio on that occasion’ (INSEE). Yet that practice extends to the home, where radio listening becomes a way of observing how other realities are woven when mobility is constrained — a way to connect with stories coming from the other islands that make up the archipelago.

Radio enables one to hear sounds as they spread, words as they are spoken, where sight can hinder discovery. In the Caribbean insular context, the radio object abolishes the sea as obstacle. These affinities and proximities with the elsewhere were monitored, even prohibited. Indeed, it is true that An tan Sorin, on 22 June 1940, “a man was questioned for having listened to his radio too loudly*“ (Archives départementales de la Guadeloupe):

“On Tuesday 29 October 1940, two police officers on patrol in downtown Pointe-à-Pitre heard a suspicious noise. A wireless set (TSF) at 24 rue Gosset was broadcasting dance music.

The police inspector immediately drew up a report. The ‘culprit’ worked in maritime transport, was married and the father of four children. He had no criminal record. He committed the offence of listening too loudly to music on Radio Haïti.

Indeed, order no. 1541 of 10 October 1940, published in the Journal Officiel de la Guadeloupe on 17 October 1940, stipulated that ‘listening to any and all foreign stations’ was prohibited in public places, as was the use of loudspeakers; and that wireless sets ‘must be adjusted so that their sound cannot be heard from outside the buildings in which they operate’.”

Archives départementales de la Guadeloupe, “La Guadeloupe « an tan Sorin », un homme inquiété pour avoir écouté sa radio trop fort.”, 10 August 2022.

Press Photo

A Sharing of Listening

Placed within the home, the radio becomes an intimate, personal object. The choice of a station, and broadcasting it through the house, entails a sharing of listening with those around us.

One July afternoon in 2024 in Bouillante, Guadeloupe, my neighbour was listening to Jamaican dancehall, blasted through poor-quality loudspeakers and subwoofers. I tried to retaliate, but the balance of power was skewed: I rather ridiculously switched on the small radio set in my uncle’s bedroom. He was lying on his bed and thanked me. To drown out the outside sound, I turned the volume up high enough for the whole house to enjoy. At 88.1 FM, Radio Haute Tension was broadcasting biguine:

“Martinican biguine, a witness since the 19th century to a meaningful evolution of the societies that created it and depend on it, results from the encounter of peoples foreign to the occupied land, while strongly marking the antagonisms of those same peoples.’ (Summary of a 2015 talk by Michel Béroard, ‘La culture musicale de la biguine martiniquaise : entre mémoire et avenir’, via the digital library manioc.org**).”

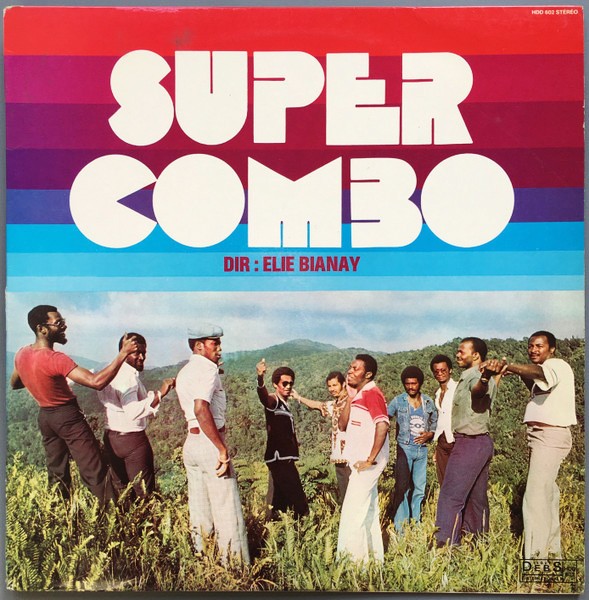

I heard the music from my room and, as it ended, I wished to keep listening some more. I went online and clicked on the first ‘Biguine’ playlist the streaming platform suggested. I listened to the album by Super Combo de Pointe-Noire, a group from the commune right next to mine. I liked it and shared the album with S., my Franco-Comorian friend in Paris, who, I was sure, would enjoy it too. In that moment I was so proud to introduce him to this music — lilting, complex — that took shape so close to home.

I could find too little information about the group. I looked at the album cover of Mèt a Mangnòk (1975) and counted eleven men, presumably the musicians. These musicians forbid us from badmouthing their line of work: ‘Pa malpalé lé muzisyen, pa trété-yo dè chyen’, because the music they share would bewitch the female public ‘pou kibiten, pou on mizik? On biten yo ka tann? Mi yo vin fòl, mi yo sédwi’:

I would mention it later to my colleagues. R. would reply, ‘but of course! I know Super Combo. Who do you take me for? I’m from Pointe-Noire!’; while D. would correct me: ‘that’s not bigin, it sounds more like kadans’, a form of modern merengue born in Haiti in the early 1960s.

I would have spent the afternoon listening to the album’s twelve tracks in my room. Once it was over, I got up and turned down the volume on my uncle’s radio. The neighbour had already packed away his gear. Each of us yielded to the Antillean night concert, which would not end until sunrise.

Folded into the performance Urgence, the radio prompts critical reflection on a central object of modern Guadeloupean culture. Beyond eliciting gestures from the performer towards the object, it invites the public to an experience close to my own in Guadeloupe: an opening towards other geographies and realities — here, Haiti — and a sharing of listening.

Guest edited by Chris Cyrille.

* Archives départementales de la Guadeloupe, “La Guadeloupe ‘an tan Sorin’, a man questioned for having listened to his radio too loudly.”, 10 August 2022. Available at: https://www.archivesguadeloupe.fr/2022/08/10/la-guadeloupe-an-tan-sorin-un-homme-inquiete-pour-avoir-ecoute-sa-radio-trop-fort/

** Béroard, Michel François. “The Musical Culture of Martinican Biguine: Between Memory and Future.” 2015. Excerpt from: Poetics and Politics of Otherness: Colonialism, Slavery, Exoticism in Literature and the Arts (17th–21st Centuries) — international conference, 12 March 2015, Colloquium & Lecture, Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Literature, Languages, Arts and Humanities (Schoelcher, Martinique), 13 March 2015. Manioc Digital Library. Accessed 14 October 2025. Available at: http://www.manioc.org/fichiers/V15164.

About the author

Kenny Cairo

Kenny Cairo is a multimedia artist and cultural worker based between Guadeloupe and Paris. His work explores the intersections of human relations, recording practices, and the experience of landscape. His recent work about the Caribbean region has mostly focused on soundscape, the experience of natural hazards, and the resilience of local communities to emergency situations.

Caribbean

Three Artists Redefining the Human-Plant Relationship in Martinique and Guadeloupe

2025 in Review

MACAS amplía su colección de arte afropuertorriqueño

Caribe

Third Horizon curates a new Cinelogue program exploring decolonial cinema and liberatory imagination from the Caribbean

A k u z u r u: Art, Post-humanism and Healing