What happens to politically engaged culture during a crisis?

For Bamako-based cultural manager Igo Lassana Diarra, the crisis in Mali turns art and culture into its own battlefield.

For Bamako-based cultural manager Igo Lassana Diarra, the crisis in Mali turns art and culture into its own battlefield.

C&: Let’s start by talking about your work with La Médina.

Diarra: La Médina Art & Culture is a child of Balani’s. The brains behind it come from Balani’s, which for over a decade now has been operating on the national and international cultural scene in a cross-disciplinary way. La Médina started to get involved in November 2011 with the exhibition “Témoin” (Witness) at the African Photography Encounters in Bamako.

C&: How have your activities been affected by the current crisis in Mali?

Diarra: The absurdity of this crisis has been traumatic for the Malian people. The cultural sector has been severely affected. Aimé Césaire once said: 'Do not fold your arms in the sterile stanceof a spectator, for life is not a spectacle.' So we decided to get involved. On May 4, 2012, we launched our 'Save the Timbuktu manuscripts' campaign and showed The Manuscripts of Timbuktu, a film by South African director Zola Maseko, at La Médina. This drew a lot of media attention because the same day we showed the film, on May 4, 2012, the mausoleums of Timbuktu were desecrated, as if our campaign had been a kind of premonition…We also created the Malian writers’ and cultural activists’ manifesto for the defense of our heritage in the occupied zones. And I directed a documentary film, Afrique avec le Mali (Africa with Mali), with leading figures from many different regions in Africa and the Diaspora, such as Achille Mbembe, Simon Njami, Domunisani, Princess Marilyn Douala-Bell, Aadel Essaadani, Narriman-Zerhor Sadouni, and Oumar Sall, to name only a few.

C&: You mentioned the manuscripts. What became of them?

Diarra: We were told that in the end things turned out better than we feared. A large batch of manuscripts is in a safe place in Bamako. The people responsible for getting them there were helped by national authorities but also by theDOEN,Prince Claus, andFord Foundations, who all responded quickly and effectively.

C&: What is your response to this situation?

Diarra: After having organized the international workshop on the manuscripts and the exhibition 'Hier, Aujourd’hui, Demain' (Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow), we are currently working on a memorial devoted to the preservation of the archives.

C&: What do collaborations within your network look like in concrete terms?

Diarra: I helped set up West African national chapters within theArterial Network. In light of the current situation, I also launched a campaign to save at-risk Malian heritage. African countries like Guinea, Gambia, and Senegal have strongly expressed their solidarity. In concrete terms, the Arterial Network together with ECOWAS cultural managers in Niger drew up a document entitled 'The Niamey Declaration,' which vigorously condemns the barbarian and criminal destruction of Malian heritage. As part of the Kya network, which brings together Malian cultural stakeholders and practitioners (founding members are Actes Sept, Balani’s,Centre Soleil d’Afrique, and the Festival on the Niger), we contributed to the revival of cultural activities in Mali with a myriad of conferences, exhibitions, festivals, and so forth.

C&: What kind of concrete effects is this having? How is it being perceived?

Diarra: The effects can be seen in the population’s raised awareness. We have stated in the press that the destruction of Malian heritage was a crime against humanity. Much to our relief, this was taken up by the Minister of Culture, whom we congratulated on taking such a clear position in his official role. UNESCO has also done what it can by placing Malian heritage sites on its 'List of World Heritage in Danger.' I do think that this declaration of principle should lead to more drastic measures to prevent such acts of destruction. We’re currently in the process of hammering out a concept of “untouchable zones” along these lines. It was Princess Marilyn Douala-Bell, the director ofdoual'art, who suggested this term during one of our discussions.

C&: How do you reach the population at large?

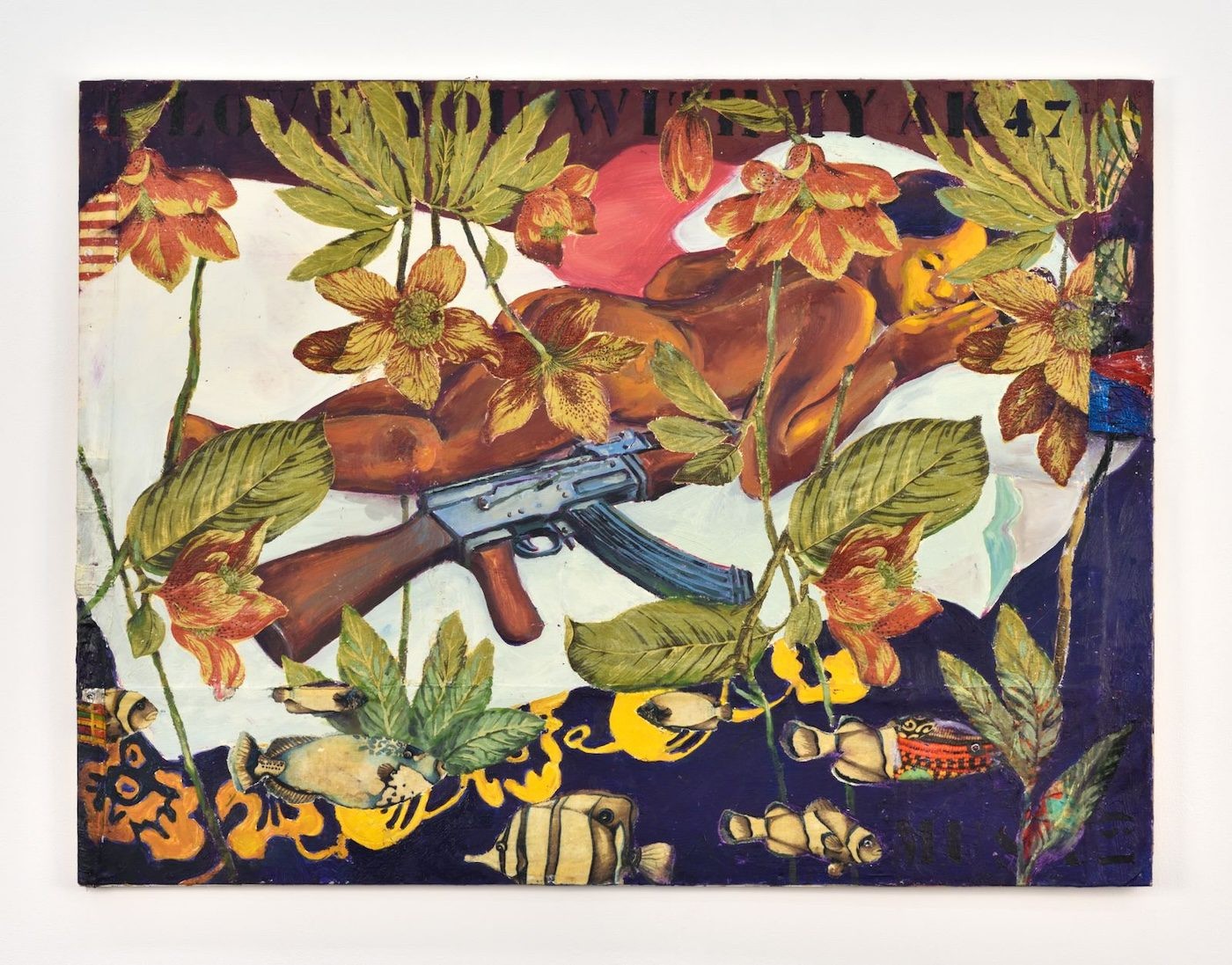

Diarra: That’s the challenge. We organize panel discussions, meetings, media interventions, and our exhibitions are also very politically engaged. For example, we make use of the press to help the population make sense of the flow of contradictory information in the media. Everyone gets involved on their own particular battlefield. In our case, we have to respond to the fact that culture has been under severe attack in this war. The number of libraries that have been ransacked – this needs to be talked about. A huge number of reading centers have been sacked and pillaged, schools torched to the ground, books burned. It’s extremely serious.

C&: How would you define the role of culture in terms of a 'battlefield'?

Diarra: You know, culture is the bedrock of every society. The intellectuals and artists in Mali have not stayed on the margins at all. To name one example, there have been many concerts for peace and politically engaged songs about the current situation. Visual artists have been extremely active; there have been a number of exhibitions on the topic. At La Médina we put up an exhibition entitled 'Presse Crises' (Press Crises) that presented press articles from around the world that talked about Mali. And just recently, 'Sacrifices Ultimes' (Ultimate Sacrifices) with the artist Ouolos was the first exhibition to take place in Mali during the curfew. It was a very turbulent time because it coincided with the arrival of the French troops. We chose the date of January 17 to commemorate the Aguelhok massacre. I even called the ministry to get a green light. During curfew, music is prohibited, as are gatherings, concerts, cinema as well. We’re virtually one of the only spaces resisting.

C&: Would you like to leave us with a particular message?

Diarra: A message of peace, of unity, and of hope. One of the conclusions I’ve drawn is that the real battlefield is in the arts, in culture, education, science, technology. That’s where the urgency lies. Resistance is an obligation. When this war is over, may the Malian rainbow shine more brightly and more beautifully than ever before.

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Resistance

Rest in/as Freedom: kiarita and Black Politics of Liberation

Sudan Art Archive Aims to Reclaim a Canon from Afar