Transmutations and Transpositions

Dagara Dakin: Can you tell us about your solo exhibitions that will be taking place in September at Backlash Gallery in Paris and in October at the 50 Golborne gallery in London? Emo de Medeiros: The Paris show is called Transmutations and the one in London Transpositions. Both are based on the idea of …

Dagara Dakin: Can you tell us about your solo exhibitions that will be taking placein September at Backlash Gallery in Paris andin October at the 50 Golborne gallery in London?

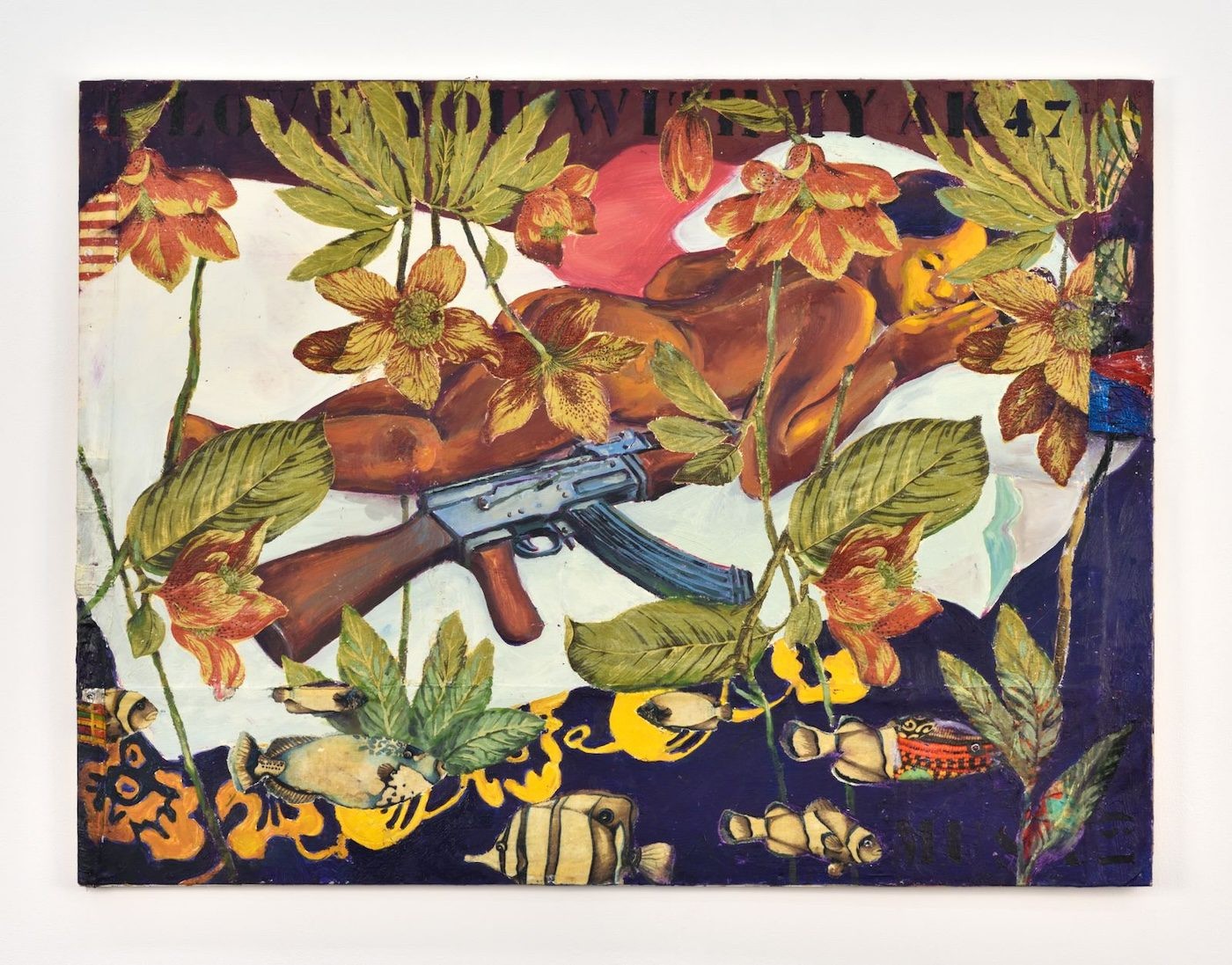

Emo de Medeiros: The Paris show is called Transmutations and the one in London Transpositions. Both are based on the idea of the alchemistic transformation of matter and consciousness. Specifically, I will show three series that I presented at the Dakar biennale: Vodunauts, sculptures incorporating video; Surtentures, fabric works that mix digital iconography and Benin's historiographical medium of appliqué; and Electrofetishes, connected sculptures that send visitors electronic messages on their smartphones, but also three new series: FAz, paintings based on the visual language of Fa divination, Metal canvasses, double-sided pieces mixing painting, text, and 3D drawing on Chinese steel transformed in Benin, and a photo series, Kaleta. In London I will additionally present my performative installation Kaleta/Kaleta that I showed in Palais de Tokyo, in collaboration with Osei Bonsu and 50 Golborne.

.

<figcaption> Emo de Medeiros, Backlash, 2016. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

.

DD: Your use of traditional artifacts is thoroughly researched and examined – you're not only interested in the visual dimension of these objects. Can you tell us more about the conceptual dimension of your approach?

EdM: Beyond the mediums and the formal dimension, my work is primarily conceptual. For me, meaning and the link to knowledge and transcendence are essential to art. The art I create would have been impossible before the 21st century, not only because of the mediums I use – such as smartphones and NFC chips – but also because it draws on the new Zeitgeist of a globalized culture and its growing transcultural dimension, facilitated by the development of planetary networks. This Zeitgeist also explains my choice of using certain “traditional” artifacts or working with artisans. I am doing it in Benin for the time being, because that’s where I live and where economic conditions allow me to do it. It would be much harder in France, for instance, but I’m also trying to work the same way in China.

My research and my practice are based on the notion of transculturality, which confronts both ethnocentric universalism and exoticism. In the 21st century, the exotic has become completely relative. So-called “traditional” artifacts are, for me as for any Beninese, totally familiar and “unexotic.” And everywhere else, all one needs is a Google search to learn what a bocio is, what Abomey’s appliquéed hangings and their narrative modes are, or the role cowries play in Fa divination and the representation of the future it proposes. Not to mention that a critical rereading of Marcel Mauss, now in the public domain, hence free and available to anyone, shows that the symbolic charge of the readymade and that of the ritual object are essentially identical.

DD: From paintings to photos, video art to sculptures, installations and music, your body of work is extremely diverse. What is the link between these different aspects of your work?

EdM: Central to all my work is the concept of “contexture.” This word means an extension of structure: the view of an ensemble, not only of its main components and their arrangement. Contexture includes these aspects but also the interrelationships between all the individual elements of an ensemble, the context in which it is located, the shifting networks that inform it, and the textures, or matrices, that animate it. Sol LeWitt created structures; I create contextures.

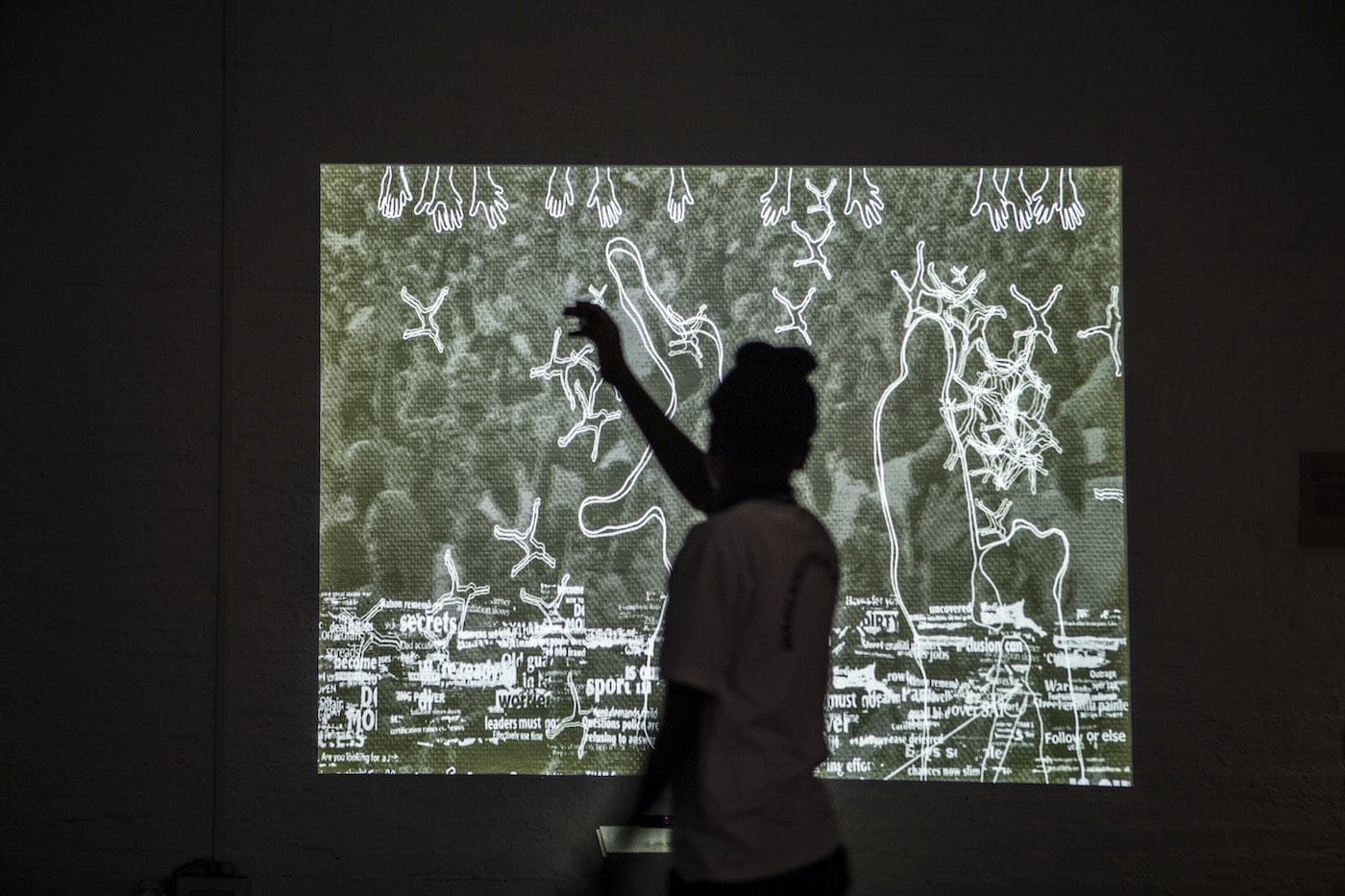

The one in Dakar was related to the texture of the museum; for its part, Kaleta/Kaleta, the one presented at the Palais de Tokyo, at the Marrakech Biennale, and soon in London, has to do with, among other things, the texture of social representation, that is, the relationship between the social mask (Jung’s concept of persona) and the transcultural properties of the physical mask as a medium of social liberation. In that piece, the Beninese tradition of Kaleta stands at the center, a mixture of Brazilian carnival, Halloween, and traditions of Beninese masks such as Zangbeto.

.

<figcaption> Emo de Medeiros, Kaleta, 2016. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

.

DD: Being both Beninese and French, what is your perspective on the concept of métissage?

EdM: I grew up in Benin, came to France for my studies, and lived in the United States before returning to France and then to Benin. I currently live in both countries, and I’m lucky enough to constantly move from one to the other. There are two complete misinterpretations of métissage. First, it is sometimes misunderstood as something akin to “half and half,” but métissage is far more than hybridization. It is a mutation that absorbs, transforms and totally exceeds its components. Métissage shares the same etymology with “textile” and “text.” In a text, it is the crossing of paradigm and syntagm that deploys the infinity of language. Language is absolutely not “half paradigm, half syntagm (1),” but rather these are only two of its dimensions.

In métissage the transmutation process is the same: moving from an imposed identity, binary and two-dimensional, to a multidimensional, chosen, and dynamic affiliation. It is a transition from mandatory tribalism to free human belonging. The second mistake is to think that métissage refers primarily to multi-ethnicity. You can of course be métis without being multiethnic: rather, the mutation occurs in a movement of expansion and transgression – whether transethnic, transcultural, or transgender. It is a revolutionary movement that erases labels and breaks down barriers. As Cheikh Hamidou Kane has written in Ambiguous Adventure, “it suddenly appears to us that throughout our journey, we have not ceased to transform, and now here we are, other.”

The best proof that métissage and multiple affiliations remain a transgression is that in France it was symbolically likened to terrorism in a prospective bill where bi-nationals were threatened with forfeiture of their French nationality. Métissage is more than a “temporary autonomous zone” as defined by Hakim Bey. It is a “permanent autonomous zone,” a symbolic territory to defend against the “great dragon” evoked by Nietzsche, or the “mental slavery” identified by Bob Marley, in other words, normative obsession and oppression.

.

Emo de Medeiros, Transpositions, October 5 - November 20, 2016, 50 Golborne, London

.

Based in Paris, Dagara Dakin graduated in art history and is a freelance writer, critic and exhibition curator.

.

(1) A sequence of words in a particular syntactic relationship to one another; a construction.

Digital art

Jazsalyn’s A(spora): On the Gullah Geechee Corridor

Sudan Art Archive Aims to Reclaim a Canon from Afar

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

Visual art

Samson Mnisi: A Master Posthumously Receives His Due

Ladji Diaby’s Sampling Sensibilities Are Material and Time-Bending