Thinking About South African Artists as the Makers of History

07 September 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

5 min read

C&: What kind of challenges did you have to overcome during the preparation and co-curation of Soul of a Nation? Zoe Whitley: The main one was geography. More than 95% of works in the exhibition were borrowed from the United States. This required frequent and intensive research trips to see artists and collectors as well …

C&: What kind of challenges did you have to overcome during the preparation and co-curation of Soul of a Nation?

Zoe Whitley: The main one was geography. More than 95% of works in the exhibition were borrowed from the United States. This required frequent and intensive research trips to see artists and collectors as well as to visit artists’ estates. The curatorial process involved a lot of studio visits and spending hours with artists asking them about their practices between 1963 and 1983, the period covered by the exhibition. We spent a number of years on clear communication and advocacy to make sure that we were able to secure the significant loans we have on view. That’s a really massive undertaking, and we’re grateful to so many artists as well as to public and private collections for collaborating with us.

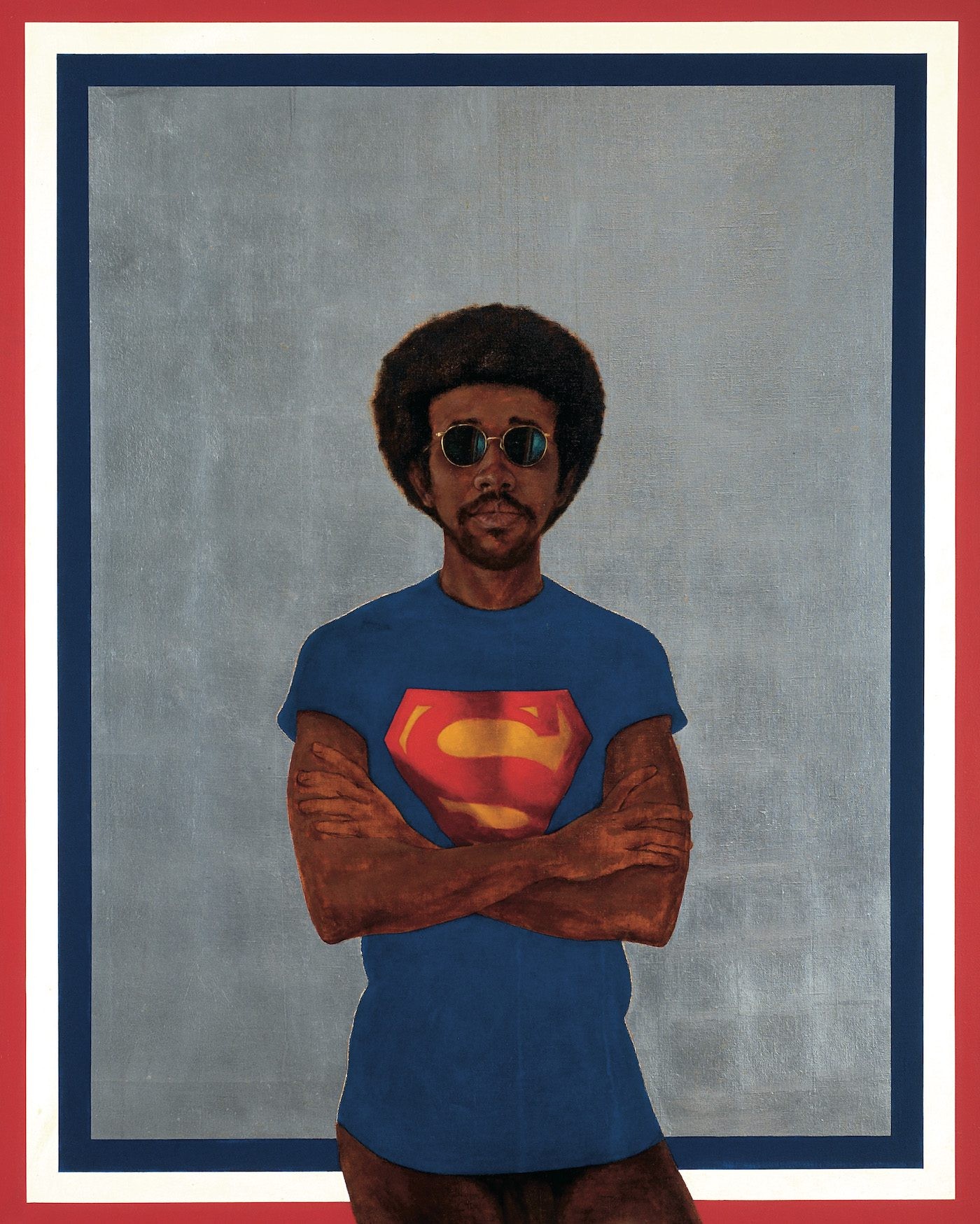

Barkley L. Hendricks, Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved any Black People – Bobby Seale), 1969. Collection of Liz and Eric Lefkofsky © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Tate Modern London

C&: What about in terms of the concept?

ZW: Our main concern was to tell a complex story from many different angles: there is no singular agreement on what “Black art” is. We didn’t want to shy away from the differences of opinion, the outright rejection of the term, and its many redefinitions. We worked diligently to specifically raise the questions that artists were asking themselves; some of them are age-old existential questions like, “Why do you make art? Do you have a responsibility to make art for your yourself? Or for your community?” Then of course there were also questions that were really specific to time and place: “What were the stakes and praxis of being a Black artist at a particular moment in US history?” So the exhibition focuses in on a twenty-year period between 1963 and 1983, and the main point that we convey – right from the first room of the exhibition – is that there is no single answer to this set of questions. There are many different responses; artists were constantly defining who they were and asserting their right to make the art they wanted to create. It’s in looking at that explosive and generative set of responses that makes the exhibition cohere.

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Floor II, 2014. Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery

C&: Did the fact that your audience is not exclusively Black play a role?

ZW: No, of course not. I mean, in the exhibition we are faithful, first and foremost, to the artists. I’m Black and I do certainly feel a responsibility to convey the history respectfully and fully. But my co-curator [Mark Godfrey] was just as committed to respect and scholarship. We want this story widely told and widely understood. We want a wide and diverse audience to come and see the exhibition; London is a super international, very diverse city. And what we have seen already is that there is a huge interest from people coming to see a show that reflects the world around us, in a way that really resonates for people.

Peju Alatise, o is the new + (cross). Courtesy the artist.

C&: Moving on to the FNB Joburg Art Fair, how are you handling that project and what are your main ambitions and concerns?

ZW: I feel very privileged to have been invited to curate a small section of the 10th anniversary Johannesburg art fair. This exhibition that I’m putting together is not a selling show. It’s really an opportunity for people to look at historically significant artworks and become reacquainted with important works that are accessible in the city of Johannesburg. The fair of course highlights the best and brightest new talents in contemporary art. But the 10th anniversary provides a very useful occasion to do a little bit of looking back and reflecting. We can think about just how hard artists had to work in incredibly challenging circumstances under the apartheid regime. It has meant having to select only a few of many artists’ works, but it’s an opportunity to bring some of their names to the fore; to think about artists as the makers of history, as people who are living embodiments of history and who create enduring testaments to history. Contradicting certain official histories is something that is fascinating to me, and it’s important to acknowledge the cultural shifts that counter-histories can bring about. It’s a momentary chance to consider the various ways in which artists document history, create it, how they themselves think about it.

Sam Gilliam, Carousel Change. Courtesy the artist.

C&: And who are the emerging artists on your radar right now?

ZW: Oh, there are so many! It’s always a challenging thing for me to say. In the South African context, I think Banele Khoza’s work is very interesting, his watercolors have have a real tenderness and grace to them. Someone like Gabrielle Goliath also comes to mind, who is a little bit better established but I find her work very moving, and affecting. Siwa Mgoboza is another artist I think is using material in a thoughtful way. iQhiya is a particularly fascinating young collective, doing really discursive, necessary work. This is leaving out Tabita Rezaire, Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Mame-Diarra Niang, and many many more. The beauty of the job is constantly learning and seeing great work being produced in a variety of contexts.

TheFNB Joburg Art Fair takes place in Johannesburg, South Africa, from September 8 to 10, 2017.

Read more from

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Read more from

MAM São Paulo announces Diane Lima as Curator of the 39th Panorama of Brazilian Art

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16