Things Fall Together Fifty Years After Things Fall Apart

C&’s Obidike Okafor reviews an exhibition celebrating a fifty-year old film adaptation of two of Chinua Achebe’s novels.

The venue for the exhibition is a well-known public space in Lagos: Tinubu Square, which is oval-shaped and not a square like its name suggests. Seventy-four large-format photographs are printed on tarpaulin and displayed on the square’s high iron railings, making the space look like a life-sized film sequence. The busy surroundings make it an ideal place to catch people’s attention, stun them with history, engage them in new information, and show them beautiful imagery.

<figcaption> Installation View of 50 years of Things Fall Apart (1971) – »Film Stills by Stephen Goldblatt« from 24 Jul 2021 - 04 Sep 2021 at Tinubu Square, Lagos. Photo: Ebunoluwa Akinbo.

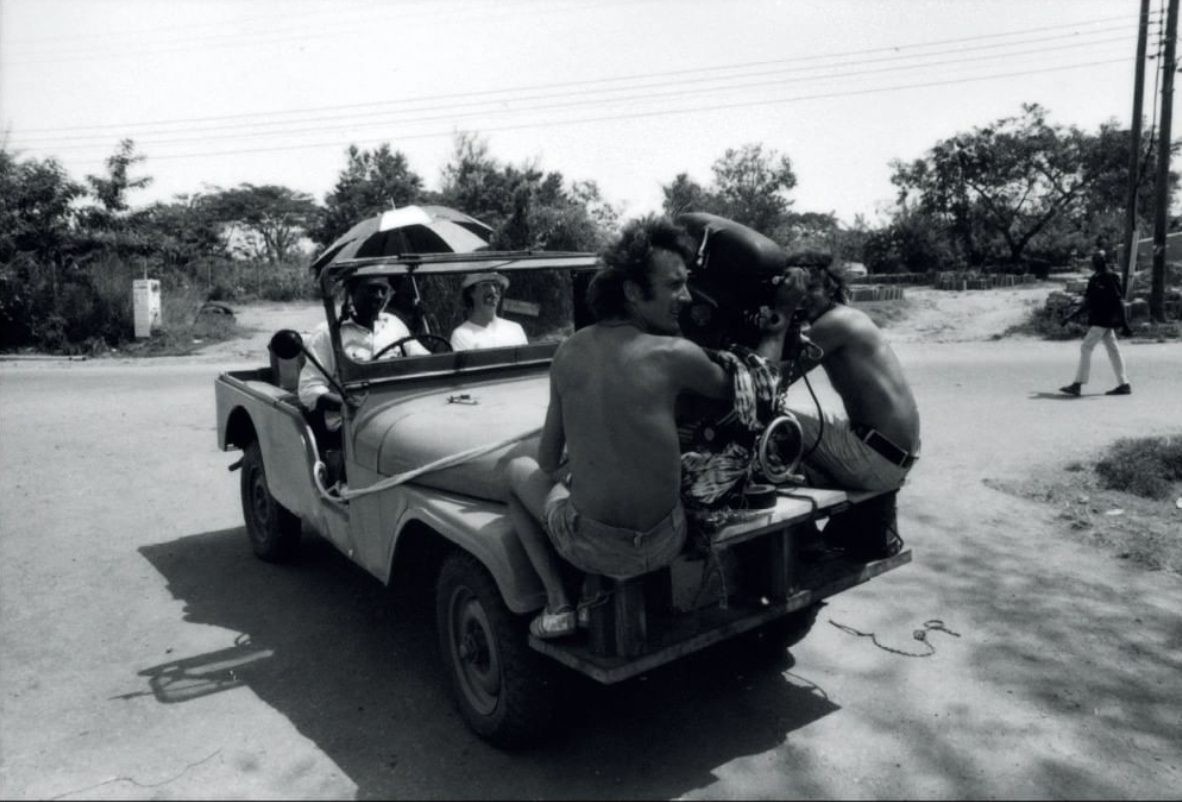

The images, part of the LagosPhoto Festival, are film stills and production photographs from a fifty-year-old movie called Things Fall Apart. They were shot by South African photographer Stephen Goldblatt, and the exhibition is curated by Berlin-based Akinbode Akinbiyi and Gisela Kayser. Goldblatt might have just been doing his job as still photographer for Things Fall Apart, but the images he created also provide valuable documentation of the history of the Nigerian movie industry – the foundations on which the present-day industry is built.

For example, one image shows the film’s director, Hans Jürgen Pohland, standing with executive producers Francis Oladele and Wolf Schmidt and author Chinua Achebe. It points to the collaboration between Nigerian literature and foreign expertise; Things Fall Apart was the first film to be shot entirely in Nigeria and it took the input of Nigerians, Germans, and Americans to make it happen.

<figcaption> Stephen Goldblatt

“We tried to select the best images to portray the best things about the movie,” Akinbiyi explained. “The images provide a view of the past so that future generations will have an idea. They talk about movies, the history of the colonial era, and the history of visualizing. You can see that it was a Kodak camera that was used for the movie, and people can relate to Kodak and its role in present-day photography and film. The images also show the importance of storytelling.”

Although Things Fall Apart was made in 1970, it was not shown in Nigeria until this year, as part of the Festival of Forgotten Films, an initiative of the Modern Art Film Archive. A copy of it was discovered by the Deutsche Kinemathek in Pohland’s estate in Berlin when he died in 2014, along with material related to the production. Even though there are different rumours circulating on why the film never showed in Nigeria, Mareike confirms that the producers had not been able to find a distribution company for the film in the United States, but this inspired the establishment of the first Black film distribution company there. The film premiered in the US, in Atlanta in 1974 and has been screened in Germany several times.

<figcaption> Installation View of 50 years of Things Fall Apart (1971) – »Film Stills by Stephen Goldblatt« from 24 Jul 2021 - 04 Sep 2021 at Tinubu Square, Lagos. Photo: Obidike Okafor

The film stars Orlando Martins – Nigeria’s first international film star in his last role – as Obierika, and Dakar-born Gambian-Senegalese actor Johnny Sekka (Obi Okonkwo) and Ugandan Elizabeth of Toro (Clara Okeke) in the lead roles. It blends elements from two of Chinua Achebe’s classic novels: Things Fall Apart (1958) and No Longer at Ease(1960).

Hollywood lawyer Edward Mosk bought the film rights to Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, with the screenplay for the film written by his wife, Fern Mosk. Then he got in touch with Francis Oladele, who had established Nigeria’s first local film production company, Calpenny Nigeria Films Limited, in 1965, and adapted Wole Soyinka’s play Kongi’s Harvest in 1970. Oladele and Wolf Schmidt became executive producers of the film and brought in Hans Jürgen Pohland to direct it. Kongi’s Harvest and Things Fall Apart arguably set up the launchpad for Nigeria’s movie industry, Nollywood.

It could be said that everything fell together for the organizers of the exhibition. They had struggled to find a venue, and yet Tinubu Square provides not only nostalgia but a geographical connection to the film. Palmeira explains that Orlando Martins was born in Lagos and a street named after his family exists close to Tinubu Square. And that Iyabo Aboaba, who also acted in the film, co-founded Freedom Park, which is likewise nearby.

As the public walk past the images, they stop to look and interact with them, and the captions and photographs provide a brief history lesson on the art, fashion, and film production process of the 1970s. They also make viewers aware that this an experience that would have normally required them to visit an art space. Most of the public will be familiar with Achebe’s book, as Things Fall Apart is a compulsory literature requirement in high school, but only become aware of the existence of the film from this event.

<figcaption> Installation View of 50 years of Things Fall Apart (1971) – »Film Stills by Stephen Goldblatt« from 24 Jul 2021 - 04 Sep 2021 at Tinubu Square, Lagos. Photo: Ebunoluwa Akinbo.

For a filmmaker, the images lay a trail of how Nigerian films first got international recognition via collaboration, and might be a good place to start conversations around building new relationships from old ties to collaborate with film production houses in countries like Germany and the US now.

The outdoor exhibition ended September 4 but the virtual one continues till December 2021 on www.modernartfilmarchiv.de.

Based in Lagos, Obidike Okafor is a content consultant, freelance art journalist, and documentary filmmaker.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission