Where are the Women Image-Makers in African History?

The photographic record in Africa began around 1863, yet women image-makers have largely been left out of the canon. When access to the camera expanded, postcolonial pioneers like Malick Sidibe, Seydou Keita, and Ousmane Sembene became highly regarded within a “golden age” of African photography and film. Who were their female contemporaries? And who came …

The photographic record in Africa began around 1863, yet women image-makers have largely been left out of the canon. When access to the camera expanded, postcolonial pioneers like Malick Sidibe, Seydou Keita, and Ousmane Sembene became highly regarded within a “golden age” of African photography and film. Who were their female contemporaries? And who came before them?

Colonial photography was an instrument of empire, occupied with the production of propaganda through a predominantly white male gaze. African women were disproportionately subjected to this gaze, hence their appointment as sitters for staged, exoticized, and eroticized postcards sent across the Atlantic to flaunt human conquest. The Black female body was on notorious display, fixed within gendered, racial, and tribal categories. As women began to access the camera themselves, they amplified the quiet acts of subversion displayed in the bodies of those early subjects. Style, pose, cloth, hair, and body language were tools of resistance, employed and read throughout the archive. By forging the event of image-making into a practice of self-expression, future remembrance, and fantasy-making, African women shaped images beyond the camera. Yet we rarely hear of those who commanded the camera.

While recorded history provides partial insight, there is a world of images and stories beyond the archive. When set against the serious gap in historical records, the lens presented women with a technology of agency over their vernacular lives – whether in the form of motion pictures or itinerant and studio photography. A burgeoning field of scholarship now aims to document African image-makers, but it was not until the early 2000s that African women gained formal recognition in the industry. As African artists create and decolonize today, we must nurture our understanding of the legacy of hidden figures: women pioneers who defied the odds and shaped an ever-evolving African female gaze.

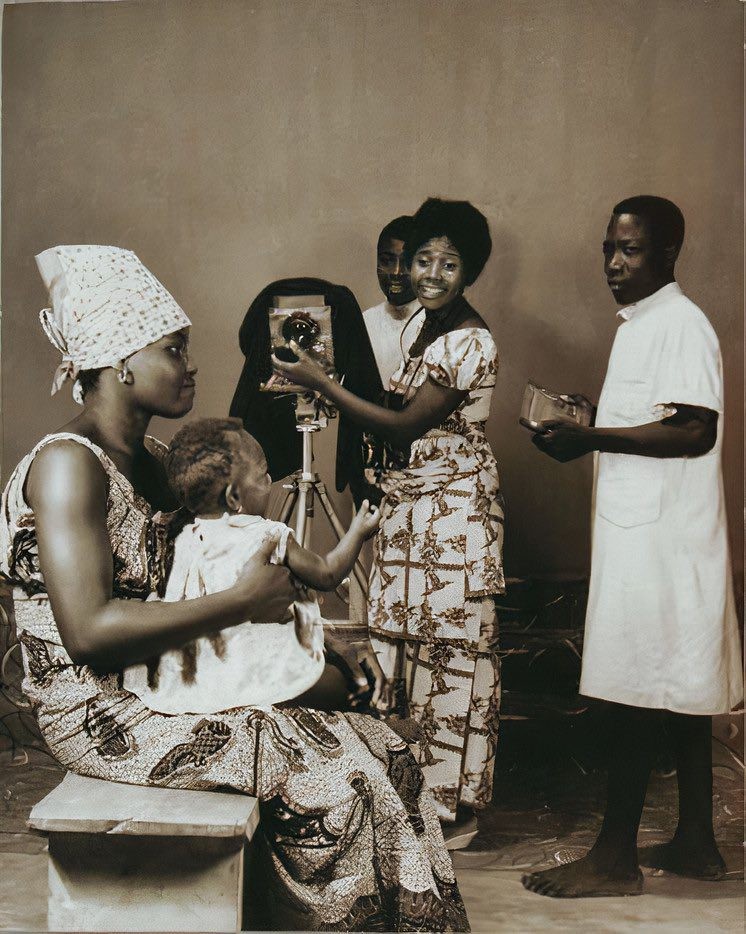

Felicia Abban (Ghana)

Felicia Ewurasi Abban (born 1935) was Ghana's first professional woman photographer. She followed in the footsteps of her father J.E. Ansah, becoming his photographer’s apprentice at the age of fourteen. In 1953, Abban opened “Mrs. Felicia Abban’s Day and Night Quality Art Studio” in Jamestown, Accra. Nearby studios included James Barnor’s Ever Young Studio and J.K. Bruce Vanderpuije’s Deo Gratias. She worked as a photographer for Ghana's first president, Kwame Nkrumah, during the 1960s. Abban also worked for the Guinea Press Limited, now known as the Ghana Times, which was the publishing house of Nkrumah’s Conventions People’s Party. Her career spanned sixty years; she eventually stopped working in 2013 due to arthritis. Abban is known for her studio portraits, trendy styling, and editorial snapshots. She was the go-to artist for post-production services, adding color and accents with detailed precision. Although her work was presented on the world stage at the Ghana Pavilion of the 2019 Venice Biennale, her contributions are yet to be well-documented in scholarship.

<figcaption> Felicia Abban. Self Portrait X.

Thérèse Sita-Bella (Cameroon)

Thérèse Bella Mbidan (1933–2006), known as Sita-Bella, was a Cameroonian film director and is among the earliest recorded women filmmakers in Africa. Her most popular work was a 30-minute short documentary titled Tam-tam à Paris (1963), capturing the National Dance Company of Cameroon during its Paris tour. The film was featured at the first FESPACO in 1969, alongside many well-known male contemporaries such as Ousman Sembene. Sita-Bella became active in radio and print journalism on the eve of Cameroon’s independence. She was also a writer, guitarist, model, and Cameroon’s first female pilot. In the 1960s, Sita-Bella cofounded and worked for the French newspaper La Vie Africane. She also worked with UNESCO, participated in the creation of BBC Africa radio service, and was a correspondent for Voice of America. After returning to Cameroon in 1967, she joined the Ministry of Information and became deputy chief of information. Sita-Bella was a trailblazer in an industry dominated by men. She died in almost total anonymity at the age of seventy-three, with most Cameroonians never hearing of her until after her death. Reflecting on the film industry, Sita-Bella is quoted stating: “Camera-women in the 1970s? At that time we were very few. There were few West Indians, a woman from Senegal called Safi Faye and I. But you know, cinema is not a woman's business."

Carrie Lumpkin (Nigeria)

Carrie Lumpkin, daughter of wealthy physician Charles J. Lumpkin, was from a community of Saros, formerly enslaved persons who repatriated from Brazil to Nigeria during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In 1908, she opened a photographic studio on Broad Street in Lagos, a favored location for photographers. Its grand opening was advertised in The Lagos Weekly Record. It is somewhat unclear whether Carrie Lumpkin operated the camera or if the studio was just part of her many entrepreneurial pursuits. Her commercial activities as a photographer may have been seen as problematic in the male-dominated profession, as gendered relations and marriage defined elite African women in Lagos. Lumpkin did not join the popular Royal Photographic Society, suggesting that she was embedded in other transatlantic photo associations in order to acquire her skills. An African female contemporary of Lumpkin’s was Tejumade Sapara-Johnson, who joined the Society in 1899. However, there is no evidence to indicate she was a professional photographer, which suggests that she may have been an amateur practitioner within elite Lagosian society.

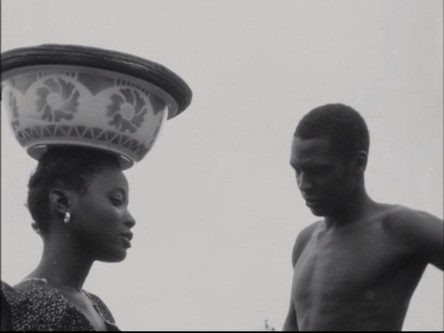

<figcaption> Safi Faye, Kaddu Beykat, 1975. Film still.

Safi Faye (Senegal)

Safi Faye (born 1943), a Senegalese film director and ethnologist of Serer heritage, was the first Sub-Saharan African woman to direct a commercially distributed feature film: Kaddu Beykat (1975). She is also credited the first to gain international recognition, as Kaddu Beykat won several awards including the FIPRESCI Prize and the OCIC Award in 1976. It was initially banned in Senegal for criticizing national agricultural policies that were remnants of the colonial era.

Faye’s interest in film was sparked in 1966, during a visit to the Dakar Festival of Negro Arts. There she met the French filmmaker Jean Rouch, who encouraged her to use film as an ethnographic tool. After acting in a small role in one of Rouch’s films, Faye went on to study ethnology. Faye disliked Rouch's film, but stated that working with him enabled her to learn about filmmaking and specifically cinema verité. Safi Faye has directed several documentary and fiction films focused on everyday experiences and rural life in Senegal. Describing her process, she states: “Even though I may write a script for my films, I basically leave people free to express themselves in front of a camera and I listen. My films are collective works in which everybody takes an active part.”

Ruth Motau (South Africa)

Ruth Seopedi Motau (born 1968) was the first Black female photographer to be employed by a newspaper at the dawn of post-Apartheid South Africa (circa 1994). Influenced by photojournalism and the marginalization of Black communities, her photography focuses on social documentary. Motau was born in Soweto and discovered her passion for photography in 1990 while studying at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. After completing the three-year course, Motau worked as an intern at the Mail & Guardiannewspaper, and then as a photographer and photo editor. She also worked as a photo editor for other newspapers, including The Sowetan and City Press. Some of her photo essays include “Shebeens,” “Sonnyboy's Story,” and “Women and Municipal Service Delivery.” Motau’s award-winning work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, as institutions have recognized its impact on documentary photography from South Africa.

<figcaption> Chantal Lawson in Women's Africa Committee Records, 1958-1978, of Sophia Smith Collection. Women's History Archive (Box 1, Folder 8, 2p.) (Northampton, MA); photographed by Evelyne Bernheim, fl. 1968 (New York, NY: Rapho Guillumette Pictures).

Mme Agbokou, MlleN’kegbe, Jacqueline Mathey and Chantal Lawson (Togo)

While little to no photo records are accessible, mentions of Togolese women image-makers appear as early as the 1970s. Mme Agbokou, a freelance journalist, and Mlle N’kegbe, who worked for Togolese Information Service, both featured work in a 1974 issue of Amina magazine. N’kegbe started her career as a professional photographer in 1964 after completing an apprenticeship in Lagos. Mlle Jacqueline Mathey was another Togolese woman who worked for the Togolese State Television Service. Chantal Lawson was one of the earliest Togolese women studio photographers, shown above in her studio in 1968, in a rare image captured by Evelyn Bernheim.

Awa Tounkara (Senegal)

One account labels Awa Tounkara (born 1949) the first female Senegalese photojournalist. She started working with Le Soleil in 1972 and was also a studio apprentice. She won best female photographer at a competition during World Press Freedom Day.

<figcaption> Fanta Régina Nacro, A certain matin (A certain Morning), Burkina Faso / 1992 / 13mins / Drama / Film Still.

Fanta Regina Nacro (Burkina Faso)

Fanta Regina Nacro (born 1962) is well-known as the first woman from Burkina Faso to direct a feature film, and is a founding member of the African Guild of Directors and Producers.

The earlier, more obscure records above are evidence of African women’s under-documented engagement in the world of photography and film in postcolonial Africa. Subordinately, non-African women photographers such as Constance Stuart Larrabee (an English photojournalist in South Africa, 1930s) and Hélène of Orléans (a French explorer in Mozambique, 1909) occupy the earliest archives of African imagery from a female gaze. However, as illustrated, combing through fragmented histories allows records of Black African women to emerge.

While the camera has slowly democratized the representation of Black African people on the continent, there were many setbacks. In 1934, the French government passed the Laval Decree to prevent cinema from spreading subversive or anticolonial messages. It was a law controlling motion pictures filmed in French African colonies, restricting African filmmakers from filming in Africa. It was only overturned in 1960. The French colonizers understood the power of cinema and photography in shaping our imaginaries, and used both to reinforce their pseudoscientific colonial experiments.

But colonial image practices were always met with resistance from African subjects. Women’s earliest contributions may be retrieved through not solely focusing on the photographer as author. Woman sitters subverted the colonial gaze in front of the camera, before gradually moving behind it and reclaiming the viewfinder. With these reckonings in mind, and as prompted by the work of Saidiya Hartman, I ask myself: How do we liberate and decolonize the archive? How do we write about these women without reducing complex nuances and the unknown? How is our history-making today expansive and how does it intentionally amplify the contributions of women in lens-based practices? What can we use from this knowledge and work to contest histories of absence?

Ethel-Ruth Tawe (b.1994, Yaoundé, Cameroon) is a multidisciplinary artist and editor exploring African identity and diaspora cultures through visual storytelling. Cyclical conceptions of time are central to her practice which examines Africa’s ancient futures from a magical realist lens. Image-making, storytelling, and time-travelling compose the framework of her inquiry. Ethel holds an MSc in Development Studies from SOAS University of London and a BA (Hons) in International Human Rights with a minor in Art History & Criticism.

Read an interview with Catherine McKinley, author of The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women, 2021,HERE.

Sources

Catherine McKinley, The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women, 2021.

Erika Nimis, “The Rise of Nigerian Women in the Visual Media, Visual Anthropology” Dibussi, 2006.

Tande, “Sita Bella: The Final Journey of a Renaissance Woman”, 2006.

Gore, Charles, “Intersecting Archives: Intertextuality and the Early West African Photographer.”, 2015.

Smithsonian, “Pioneering Women Photographers in Africa”, 2019.

Billie Mcternan, “Felicia Abban: Behind the Scenes’. Published on Contemporary And, 2019.

Jennifer Bajorek, ‘Unfixed: Photography and Decolonial Imagination in West Africa.’, 2020.

Amina Magazine ,‘Therese Sita-Bella Talks About the Press & Elegance’, 1989.

Lorena Rizzo , “Photography and History in Colonial Southern Africa: Shades of Empire.”, 2019.

Saidiya Hartman , Venus in Two Acts, in Small Axe, Volume 12, no. 2, pp. 1–14. Small Axe, Inc., 2009.

Chantal Lawson, in <span data-field="archive_collection">Women's Africa Committee Records, 1958-1978, ofSophia Smith Collection. Women's History Archive (Box 1, Folder 8, 2p.) (Northampton, MA); photographed by Evelyne Bernheim, fl. 1968 (New York, NY: Rapho Guillumette Pictures).

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Visual art

Samson Mnisi: A Master Posthumously Receives His Due

Ladji Diaby’s Sampling Sensibilities Are Material and Time-Bending