Maxwell Alexandre: “There is a Future Changing the Imagination of Subalterity”

03 March 2021

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Anna Azevedo

8 min read

The boy who was born in 1990 stepped into his inline “blades” for the first time at 14, became a professional street skater afterward and made his skates the first paintbrush of a meteoric career. In only four years, his work as an artist had already become known worldwide. On a hot summer afternoon in Rio, Maxwell Alexandre summed up the stages of his trajectory in a conversation with C& América Latina.

From Skates to Museums

I always drew pictures, but around the slums, an artist was an actor on the evening soaps on TV. In 2011, I enrolled in the Design Visual Communications course. I wanted to become a professional so I could promote street skating culture. But the program exposed me to much more than industrial drawing and I became aware of what a plastic artist was. Since that blooming, I was able to look retroactively and identify much of what I had been doing as art, like the works with video and photography I used to make to promote my career as a skater. Skating was also an artistic activity.

From the Alleyways of the Slums to the Halls of the Elite

I studied on full scholarship at PUC-Rio, an elite university. Most of the time, I was the only black student in the classroom. Of course, our body, our presence, alters the environment and brings feelings and responses, but in college I didn’t think much about those things; debates about identity weren’t that heated yet. It was during college that I really came to know myself and I accepted myself as black and I came to feel immense pride of my community. As I was finishing my degree in 2016, I began a process of repatriation. I started walking barefoot as a way to speed up my return home, to Rocinha, I tried to change my routine again to readapt. I went out dancing. I played soccer with my childhood friends, but it was awkward, because everyone noticed that I was no longer the same. To make matters worse, I had no future perspective and at the same time I didn’t really like the idea of a formal job. Expectations at home were high. Particularly, because I was making abstract art. I spent the day scribbling on paper, imagine: almost thirty years old scribbling on paper, in the slums! The expectation was: now that you’ve graduated, you will develop yourself. But I went in as a designer and I came out an artist! For most people, I was a vagabond. I was always very focused. I was committed to my artistic research, and I took a risk.

Close a Door to Open a Window (detail), 2020. Courtesy of the David Zwirner Gallery

It all changed quickly

My studio is also in Rocinha. The first time I painted subjects wearing a public school uniform (2017), I thought: “Fuck. This is my breakthrough!” Because there was a demand for it! A growing context of minorities reclaiming their spaces, a surging wave of black artists portraying themselves as what it is to be black. The markets eat up everything and I was on my toes, surfing the same wave. I had an icon, the uniform that is in the city streets and everyone recognizes. But bringing it to the canvas changes everything. It’s powerful, I know that, and I knew that I was creating a space of exclusivity, since I knew how to talk about it. It no longer works for someone from outside, who dominates the codes of contemporary art, to come into the periphery, speak, and create works about the periphery. For this movement to be legitimate, we would need someone from the periphery who dominated the codes of contemporary art to come back to the periphery and develop for the world a poetically sophisticated language within those codes that contemporary art affords to us. And I had a repertoire to represent that content through painting, within the codes of contemporary art. That was my space of exclusivity.

References

Black painters who portray black subjects are rare. My references were the North American Kerry James Marshall and, here in Rio, Arjan Martins. Without these masters, we would have black artists painting whites. The process is really insane, man, and in art it is more obvious. Even being black, experiencing being black, the artist’s palette is going to be ochre, pinkish. Kerry James Marshal has painted black subjects since the 1990s. He had a reference, Charles White (1918-1979). But without a reference… Now it seems simple, I go on the internet and I see people painting black people, even white painters are darkening their palette. But the first guys had it most difficult; they had to think: why am I painting white subjects? Today, we have Mulambö, No Martins, several artists who started their career portraying black subjects, whether or not they are in a position of subalterity. We don’t have well-known great black masters, because painting is a an idle practice for the privileged. Where were the black masters? Working hard.

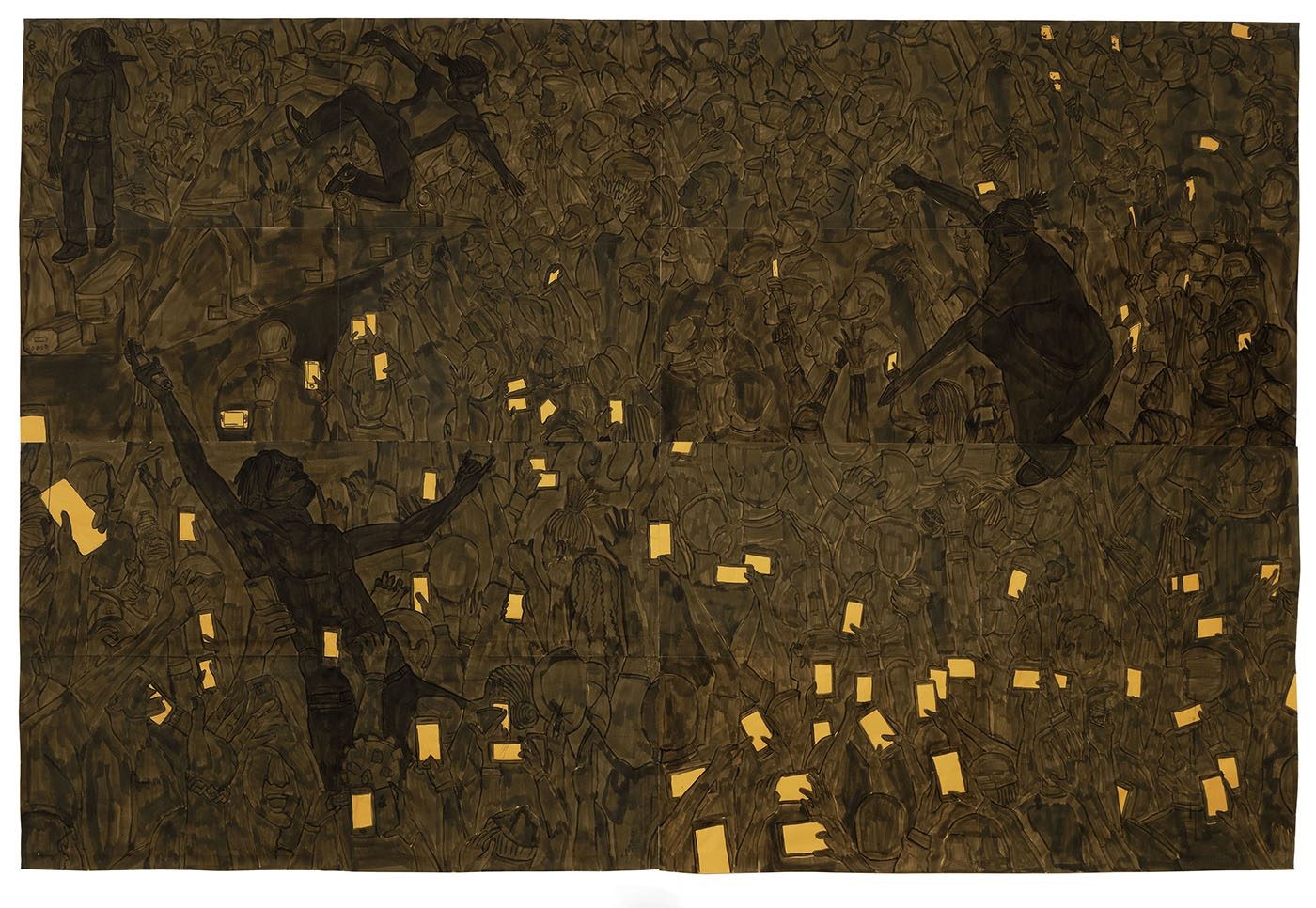

I Saw Things I Imagined, 2020. Courtesy of the David Zwirner Gallery

The Narrative of “Pardo é Papel”

The series “Pardo é papel” (Pardo is Paper) began its itinerancy in 2019 in France. Form and content complement each other with precise coherence. The subjects are black. And the paper is brown, a color that has been commonly used in I.D. cards as a sort of act of veiling Negritude. This coincides with the black community’s coming to consciousness about itself. Initially, this connection was not made. In the first self-portraits I painted, using leftover kraft paper from PUC’s Fashion workshop, the idea was purely aesthetic: to create a universe where the characters were black, and they had blond hair, like mine, bleached since 2012. And the yellowish background of the paper comes out of a very aesthetically appealing response. In the third drawing, I made the connection that I was painting black bodies on brown paper and I remembered the maxim of the black movements: “Pardo is paper.” I shut down the concept head-on! Around the same time, I was painting the series “Reprovados” (Failed), analogous to “Pardo é papel.” But “Failed” is about sorrow, the decimation of the black population. The principal motivation is the public school uniform. Now, “Pardo é papel” is about black big shots boasting victory, in prosperity. I wanted to launch “Pardo é papel” first, because I didn’t want to begin with a discussion of sorrow; I wanted to talk about glory. Cos victory isn’t as speculative anymore; we’ve got hip hop culture, where various powerful and rich black voices come out. And this continuously changes our imagination with respect to black people. I think that that is the greatest contribution that we, black authors, can bring, meaning, portraying the reality that there is a speculative future of victory, of ascension, changing the imagination of subalterity.

Media

There are those who say: “paint on canvas!” But I paint on canvas before I paint on paper. When I choose to paint with shoe polish on brown kraft paper, I am not thinking of the polish as a material that can speak about the narratives I am painting.

Actually, shoe polish was the material I used when I served in the army; so, there is a memory attached to it. But, most importantly, because it’s a material that is accessible. When I began to paint, I didn’t have any money to buy paint. I would use the materials I could find. Henna and shoe polish come from this. I use a lot of pure pigments. Dye is very cheap, two reais. For shoddy wall paint, I only spend 20 reais and my results are porous and matte, which I really like. Back then, when I was starting out, my decisions came out of necessity. Afterward, using the same materials ended up being conceptual for me. In terms of media, I work with what comes to me. I’ve done a lot of work in photo and in video, and performance… What happens is that “Pardo é papel” was the work that blew up, and my career is recent.

Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Vitória Proença

The Future

I have my own mythology and painting is its cervical spine – which represents more than 50% of the market, even in commercial terms. Actually, I don’t even consider myself a painter. I practice painting, just as I practice writing. Painting is merely my way of taking notes.

The individual exhibition “Pardo é papel,” by Maxwell Alexandre, at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAR) is open for virtual visits at the website:inclusartiz.org

Anna Azevedo is a journalist, artist and filmmaker interested in the intersection between cinema and the visual arts.

Translation: Sara Hanaburgh

Read more from

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Read more from

Rest in/as Freedom: kiarita and Black Politics of Liberation

Modupeola Fadugba Wins The Norval Sovereign African Art Prize 2025