The State of Visual Arts in Lesotho

Lesotho is experiencing an artistic renaissance driven by its millennial generation, specifically in the area of visual arts. Historically, the arts in general have been afforded some attention, mainly in the disciplines of music, dance, and literature, most of which remained static and lacking in innovation for a great many years. As a society, …

Lesotho is experiencing an artistic renaissance driven by its millennial generation, specifically in the area of visual arts. Historically, the arts in general have been afforded some attention, mainly in the disciplines of music, dance, and literature, most of which remained static and lacking in innovation for a great many years. As a society, we have grown more exposed to technology and global trends in the past two decades. This has come especially with the spread of Internet access, which is translating into young Basotho boldly pursuing projects that present opportunities to mark our place on the world stage. Although there is still a stigma around the arts, our government is making concerted efforts toward prioritizing creative enterprises as an agent of economic and social development. So local talent is arising in areas such as fashion design, visual art, photography, filmmaking, and performance art, the sum of which is being crafted into imaginative careers.

.

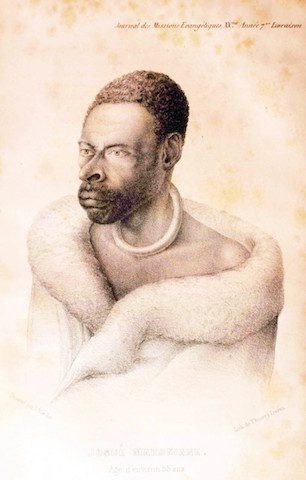

<figcaption> François Maeder, Artifact Joshua Nau Makoanyane-Moshoeshoes military commander, 1845

History of Visual Art

Visual art on the topic of the Basotho and their history was recorded by European missionaries and settlers from 1845 until the latter half of the 20th century. This means that, in spite of being cognizant of the natives and their lifestyles, the foreign artists’ anthropological gaze was influenced by them contrasting the African way of life to their pre-established European ideologies and perspectives. Missionaries, fascinated and intrigued by these “exotic” people, wrote books, learned the language, drew sketches, built schools, and introduced European culture to their new communities. Some went as far as enthusiastically assimilating into the local communities despite the boundaries attached to that engagement. One such example is that of German-born François Maeder, who was the first artist and artisan missionary to document the lives of Basotho.

There is a big time gap between the era of Maeder and that of Paul Ncheke, the first historically recorded prominent Mosotho visual artist. Ncheke only surfaced in the late 1950s and early 1960s and is rumored to have learned his craft from Ephraim Ngatane, about whom even less is known. Fast forward to 2016 and the most famous fine artist from our tiny mountain kingdom is 90-year-old Meshu Mokitimi, who is greatly admired by a rising movement of youth involved in the arts. Yet it is worth mentioning that visual arts by definition did not arrive with Europeans: plenty of cave drawings and paintings which pre-date the 1800s are scattered across the country. The people responsible for those symbols of past times are the San, the original inhabitants of southern Africa before the Bantu and Nguni tribes arrived and settled.

Our current generation of visual artists, and photographers in particular, are motivated by an irritation with often negative photographs of Lesotho/Basotho, that is, photographs that are clichéd or oriented to serve foreign companies’ commercial interests. We are aware of the power of an image and want to show Lesotho’s little-appreciated yet fantastic natural beauty and to tell the stories of its people. Our aim is to illustrate life here through our own eyes: our loves, hates, and frustrations. The lens calls for us to expose the myriad of dramas we face as individuals and collectively as a nation. Wim Wenders articulates it best: “The most political decision you make is where you direct peoples’ eyes. In other words, what you show people, day in and day out, is political... And the most politically indoctrinating thing you can do to a human being is show him, every day, that there can be no change.”

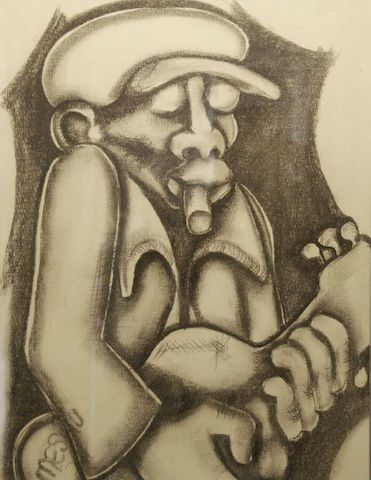

<figcaption> Meshu Mokitimi, Self-portrait, 1978

The Rise of Photography

Photography has enjoyed a consistent popularity in Lesotho because, like any other nation, we are quite sentimental and like to archive the highlights of our lives in albums. Photographers – mostly gentlemen in signature leather jackets – would either roam through villages in pursuit of capturing moments for the eager or market their skills to secure future bookings, especially during major holidays. People who owned cameras for purposes outside of making a living would shoot pictures for fun and hardly viewed photography as an art, let alone a profession. It was with the rise of digital photography in the 2000s that the likes of Neo BJ Tau and then the late Hlompho Letsielo set up offices with the intention of trading in high-quality images. Public perception began to shift, albeit slowly.

The dawn of digital photography meant that film was being phased out and people no longer had to wait up to a month to see their images. It also meant that people could scrutinize pictures before they were printed and the pictures themselves could be enhanced. Obviously this made shoots more expensive, which is where public resistance came in. Upon his death, Hlompho revealed that one of his major frustrations was the fact that people appeared quite comfortable with exploiting his work without compensating him. The unfortunate reality is that the best photographers in Lesotho are respected based on the families or figures of power they are affiliated with. Those who do not have this kind of privilege are scrutinized as either being too cheap (therefore perceived to produce doubtful quality) or too expensive (because capturing light and editing and producing high-quality images are considered child’s play).

<figcaption> Hlompho Letsielo, Old Post Office facade Kingsway, Maseru, Lesotho, 2012. Courtesy of the artist

Secret Agreements

In spite of the absence of exhibition spaces, galleries, and training facilities, more youth are taking up photography with the intention of pursuing it as a professional career. Yet at this point people are more inclined to pursue advertising, weddings, and events than documentary work because these pay. Only a select few are confident enough to capture images that reveal or confront uncomfortable topics such as poverty, political turmoil, and unemployment. It is not that the desire to tackle such themes is not there for other photographers; rather, the condition is created by insufficient infrastructure and mentorship to guide the process. The struggle to be taken seriously is a challenge all creatives have to deal with, especially when they present new ideas. When you come from a country where the typical narrative (in images) is that of mountains, people on horses, thatched mud huts, and other stereotypical depictions, the camera becomes a form of power and power is not an easy thing to manage.

A secret agreement has formed among the majority of local photographers to learn from and groom each other. There exists a sense of communion which inspires creativity and motivates a truthful representation of life in Lesotho, one that is contrary to the Western gaze that usually dominates. It is a bit difficult to trace what is going on in other realms of visual art due to the absence of a publicly available, comprehensive database of the artists as well as the means to travel to the more remote areas of the country. I dream of a complete roll-out of arts education in all schools around the country because then apprentices would be identified, recorded, and easier to reach. Once formalized and set firmly in place, a rationale for better infrastructure for visual and other forms of art can be developed and implemented so that Basotho children can thrive. We are pumped up to unleash an assault of visual brilliance from our tiny mountain kingdom to the rest of Africa and the world.

Lineo Segoete is the co-director of Ba re e ne re literary arts in Lesotho and a freelance writer and wanderer governed by creativity. Follow her onTwitter andInstagram.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025