The Short Century

The exhibition The Short Century. Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994 opened in 2001 in Munich. Initially conceptualized for the museum Villa Stuck, it then traveled to Berlin, Chicago, and New York. Okwui Enwezor, curator, critic and in the meantime director of Haus der Kunst in Munich, took on the task of organizing this …

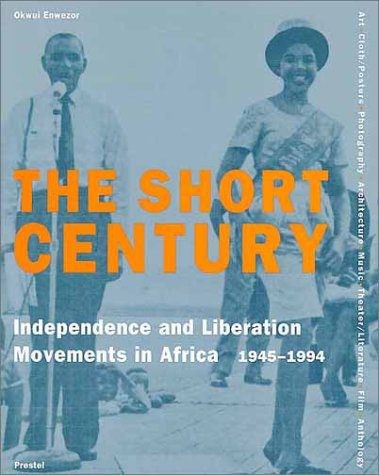

The exhibition The Short Century. Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994 opened in 2001 in Munich. Initially conceptualized for the museum Villa Stuck, it then traveled to Berlin, Chicago, and New York. Okwui Enwezor, curator, critic and in the meantime director of Haus der Kunst in Munich, took on the task of organizing this epic show. The first German blockbuster exhibition of contemporary art from the African continent was born.

Concept and critical review

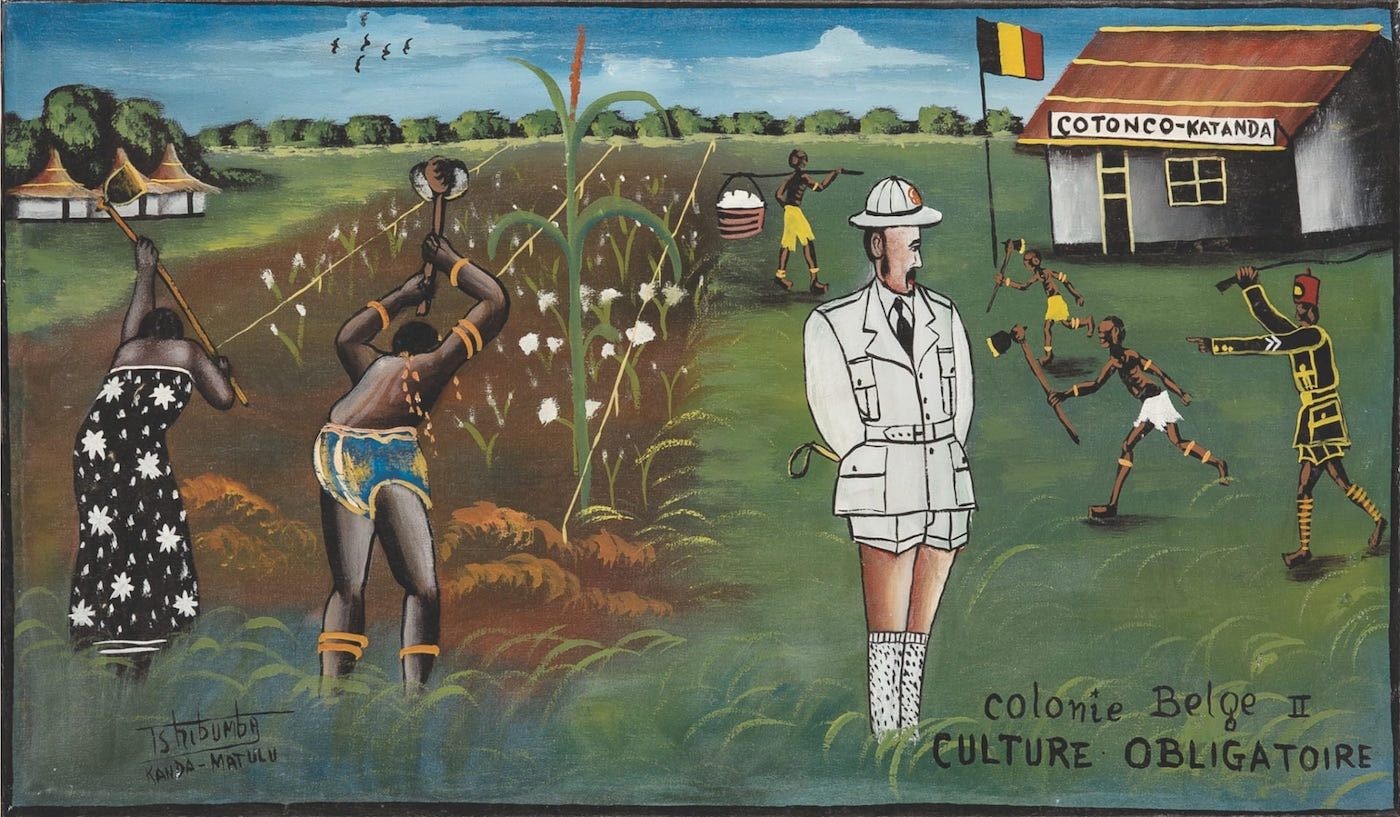

In The Short Century, Enwezor reopened the case of independence movements in Africa and promoted an intensified analysis of this significant epoch: “Decolonization, and its attendant ideological and philosophical contestation of Western imperialism, does (…) remain one of the most significant events of the twentieth century (…).”[1] In his exhibition he ventured a trek across all forms of artistic production and presented visual art and photography, but also architecture, film, music or graphic art. However, the essential feature of the show was the historical classification of the works. The Short Century stands for the momentous period in Africa’s history, during which more and more states gained their long awaited independence: it represents the beginnings of autonomy accelerated by the Pan-African congresses through to the collapse of apartheid in South Africa. According to Enwezor, the time also marked the beginning of a new cultural era; the newly gained sovereignty was reflected in artistic production and the confident establishment of an ‘African modernity’.

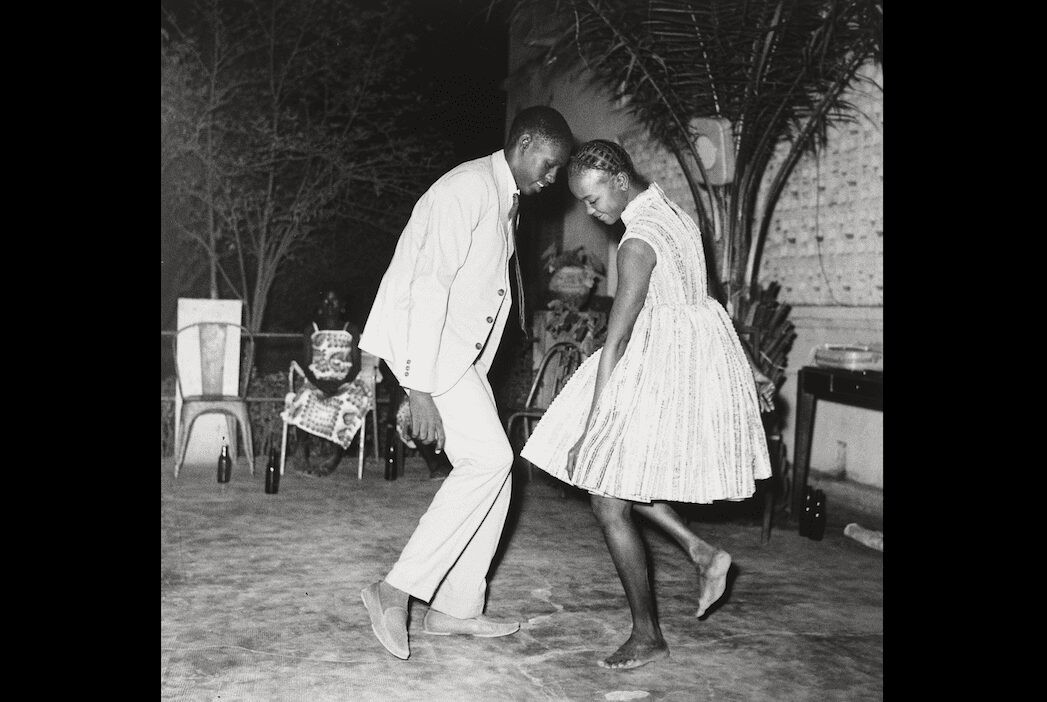

<figcaption> Malangatana Ngwenya, Untitled, 1961.

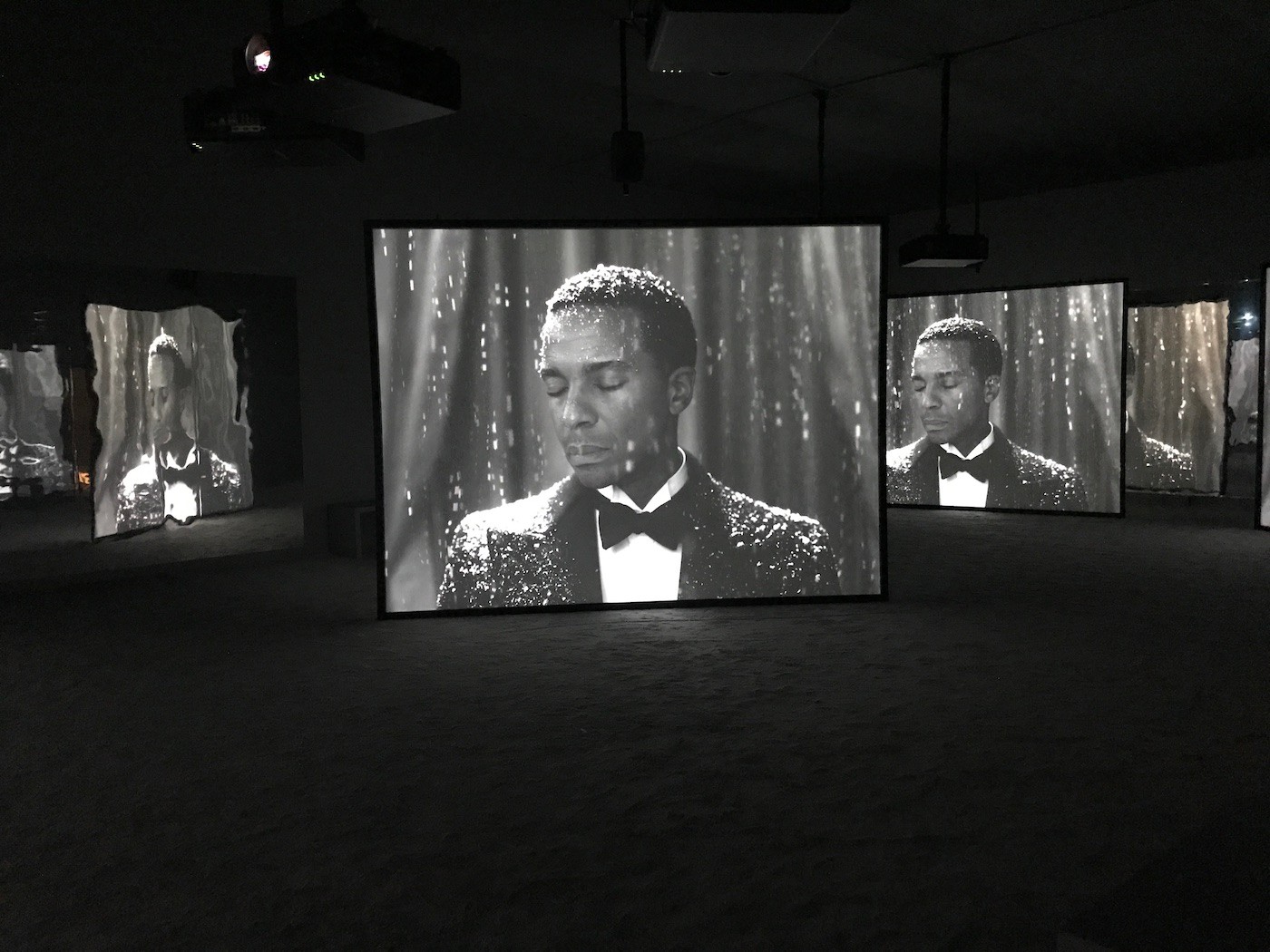

With The Short Century the curator wanted to point out how closely the awakening of this new cultural identity was tied to the transformation of political conditions. Movements such as the Négritude and Pan-Africanism not only fought for political autonomy but also for a new African confidence that manifested itself in art, music or literature.[2] The catalogue therefore contains a comprehensive compilation of political manifests, speeches and historical photographs supplementing the artworks and contributing to a better anderstanding of this era. The works were arranged according to genre, which Enwezor coordinated with advising curators: Rory Bester lent his support in the architecture section; Lauri Firstenberg in graphic art; Chika Okeke attended to visual art. As co-curator, Mark Nash took on the area of film. In total, works by more than 50 artists from 22 African countries and the Diaspora were on display, including works by Malick Sidibé, Skander Boghossian and Jane Alexander. Along with the historical documents, these works in The Short Century were intended to demonstrate the dynamics of a time in which political transformations in conjunction with experimental artistic forms of expression laid the foandation for a new era which influences the practice of artists from Africa and its Diaspora to this day.[3]

<figcaption> Samuel Fosso, From 1970's self portrait, date unknown.

The Short Century was generally well received by critics who most of all praised the participation of numerous unknown artists, as well as the mere fact that these artistic positions from Africa were taking their legitimate place in large-scale museums in Europe and the US.[4] However, the historical and political backgroand, the relevance of which Ewezor placed so much emphasis on in the catalogue, was rather vaguely presented in the exhibition. According to Justin Hoffman, visitors foand it difficult to link the historical photographs and documents with substance, quite simply because there were no explanations. Being able to follow the exhibition’s narration required solid foreknowledge of the continent’s history, which Enwezor certainly could not expect of the audience.[5] The gigantic format of the exhibition did also not remain without reflection. For example Ashley Dawson wondered in how far a blockbuster show could do justice to such a comprehensive and complex topic. According to him this brought with it the danger of a ‘sellout’ which was accelerated by the interest of the international art market. Although the curator had made the effort of a diversified portrayal, the show, according to Dawson, also exhibited a simplified, equalizing version of independence movements in Africa.[6]

<figcaption> Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, Paintings from The History of Zaïre Series, November 1973 - November 1974.

Relevance

The exhibition The Short Century, that can today be viewed as predecessor to Enwezors documenta 11 in Kassel, has a high significance in the history of exhibitions of ‘non-Western’ art and culture despite individual points of criticism. Through traveling and the blockbuster format the show reached a wide audience, heralding an intensified engagement with contemporary art from Africa and the era of independence movements. Furthermore it emphasized that this period was indeed not an ‚African‘ matter but globally marked a turning point of the 20th century, which not only involved political, economic and social shift but also a philosophical and ideological one.[7] Enwezor deeply challenged the inherited burdens of reactionary world views that have an impact until today: in The Short Century he was able to mediate an image of Africa that effectively stands up to our negative media coverage on the continent – one of a modern, assertive continent.

<figcaption> Catalog for the exhibition "The Short Century", 2001.

Involved Artists

Georges Adéagbo, Jane Alexander, Ghada Amer, Oladélé Bamgboyé, Georgina Beier, Zarina Bhimji, Skunder Boghossian, Willem Boshoff, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Ahmed Cherkaoui, Gebre Kristos Desta, Uzo Egonu, Ibrahim El-Salahi, Erhabor Ogierva Emokpae, Touhami Ennadre, Ben Enwonwu, Dumile Feni, Samuel Fosso, Kendell Geers, Kay Hassan, Kamala Ishaq, Gavin Jantjes, Isaac Julien, Kaswende, Seydou Keïta, William Kentridge, Bodys Isek Kingelez, Vincent Kofi, Rachid Koraichi, Sydney Kumalo, Moshekwa Langa, Christian Lattier, Ernest Mancoba, Santu Mofokeng, Zwelethu Mthethwa, John Muafangejo, Malangatana Ngwenya, Thomas Mukarobgwa, Iba Ndiaye, Amir Nour, Uche Okeke, Antonio Olé, Ben Osawe, Ouattara, Gerard Sekoto, Yinka Shonibare, Malick Sidibe, Gazbia Sirry, Lucas Sithole, Cecil Skotnes, Pascal Marthine Tayou, Tshibumba, Twins Seven-Seven, Susanne Wenger, and Sue Williamson.

Julia Friedel is the research curator for the African section atthe Weltkulturenmuseum and writer, living in Offenbach am Main. She studied African languages, literature and art (Bayreuth) and curation (Frankfurt am Main).

Translated from German by Ekpenyong Ani.

Further Reading:

Ashley Dawson, 2003: The Short Century: Postcolonial Africa and the Politics of Representation. In: Radical History Review, Nr. 87. S. 226-236.

Okwui Enwezor (Hrsg.), 2001: The Short Century. Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994. München: Prestel.

Justin Hoffman, 2001: The Short Century,http://www.frieze.com/article/short-century

Kennell Jackson, 2003: Okwui Enwezor, ed. The Short Century. In: African Studies Review. S. 152-153.

Chika Okeke, 2001: Modern African Art. In: Okwui Enwezor (Hrsg.), 2001: The Short Century. Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994. München: Prestel. S. 29-36.

[1] Enwezor 2001: 10.

[2] vgl. Enwezor 2001: 10-14.

[3] cf. Enwezor 2001: 14 and Okeke 2001: 30.

[4] cf. Hoffman 2001.

[5] cf. Hoffman 2001.

[6] cf. Dawson 2003: 227 and 229-230.

[7] cf. also Enwezor 2001: 16 and Jackson 2003: 153.

Art exhibition

Noah Davis

Skånes konstförening Appoints Tawanda Appiah as New Curator

Nana Oforiatta Ayim on Ghana’s First Ever Pavilion at Venice

Okwui Enwezor

Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present II

Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present