The Collective Unearthing: Censored Scenes from Postwar Italian Cinema

19 March 2018

Magazine C&

5 min read

. C&: Who is Radha May? Radha May: Radha May is an artist collective working under a single identity. I work with historical and social archives to explore hidden histories and feminine myths, often around female sexuality. I reveal what was once kept hidden and I circulate it in the form of films, installations, performances, …

.

C&: Who is Radha May?

Radha May: Radha May is an artist collective working under a single identity. I work with historical and social archives to explore hidden histories and feminine myths, often around female sexuality. I reveal what was once kept hidden and I circulate it in the form of films, installations, performances, and publications. I believe that by making subaltern histories visible, new shared memories emerge which create a potential history, that not only alters our relationship with the past but also the present and future.

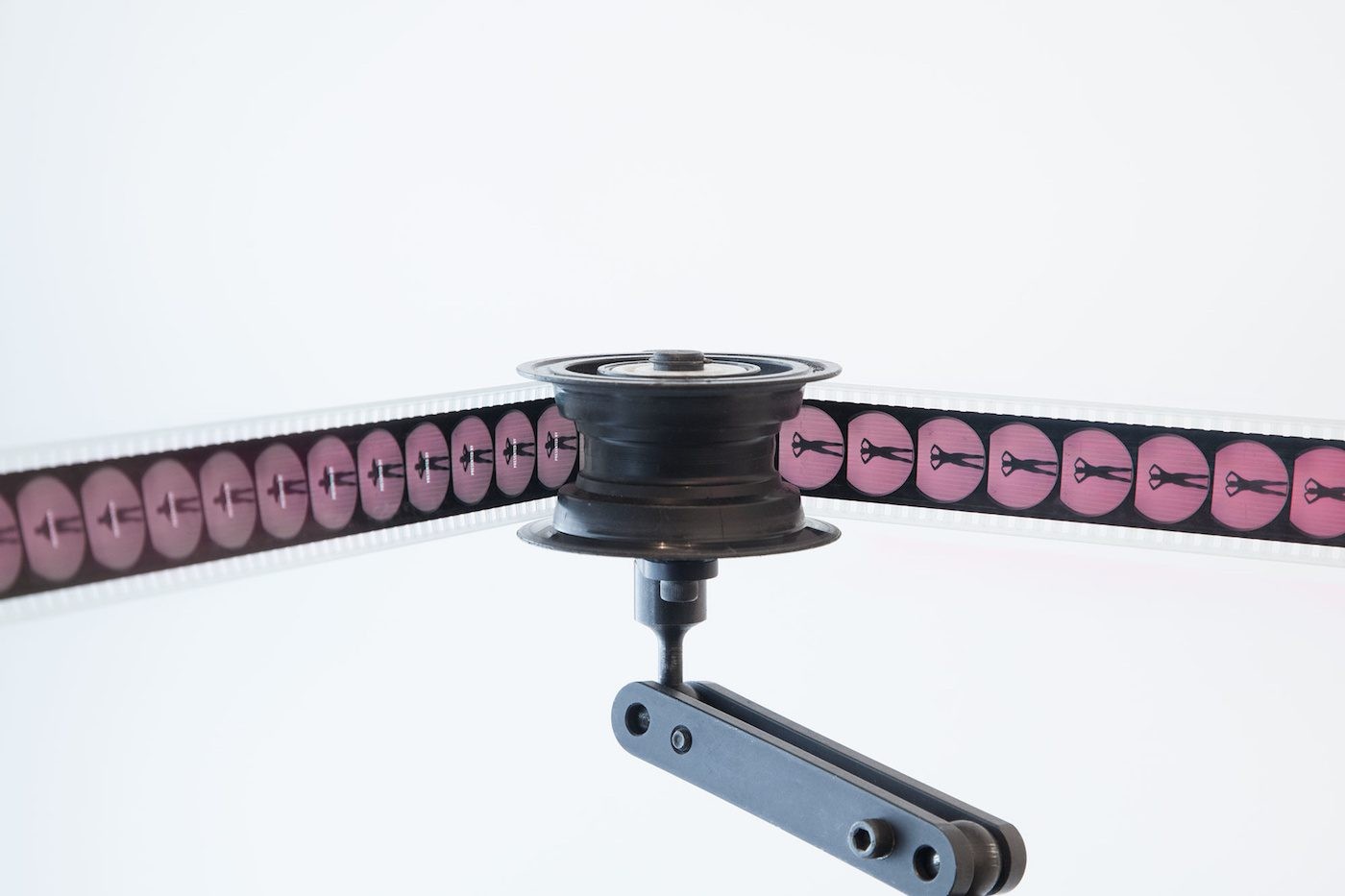

Radha May, 35 mm installation, When the Towel Drops Vol 1 Italy, Granoff Center for the Arts, Rhode Island, USA

C&: When the Towel Drops is a 35mm film installation that explores censorship of female sexuality in Italy in the 1950s and 1960s. What led you to investigate Italian cinema and censorship?

RM: Soon after Radha May formed, I learnt that the Cineteca di Bologna housed film scenes that had been removed from publicly viewed cinema in Italy. I visited the archive and viewed hundreds of censored scenes. I was drawn to the ones of women expressing desire, provocation, and defiance that had been censored during the early post-World War II period. And I started to recognize patterns in the agenda of the censorship committee: the acceptable Italian woman of the time was not supposed to be sexually explicit or provocative, she was not supposed to challenge either patriarchy or the Catholic authority, she was not even supposed to give birth on film. My installation is the result of a wide range of these censored scenes, such as: a woman giving birth from Ingmar Bergman’s Nära livet (Brink of Life, 1958), a woman moving her hips during a dance in Mauro Bolognini’s La Notte Brava (The Big Night, 1960), and a woman masturbating in Joseph Sarno’s Inga (1968). While at the archive, I also found the official documents that justified the removal of these scenes. What these official justifications do is present censorship as a negotiation of creative, moral, and substantive acceptability between the state authority, filmmakers, and audiences.

Radha May, When the Towel Drops Vol 1 Italy, Performance, Fabrica del Vapore, Milan, Italy, 2016

C&: It’s interesting that the censors inadvertently construct an idea of women as powerful sexual beings and men as powerless, vulnerable, and weak by prohibiting specific expressions of female sexuality. In unearthing these justifications, you reveal their stereotypical and sexist notions of sexually assertive women. Is this why historical and archival research is so essential to your practice?

RM: Historical and archival documents reveal systems around which realities are constructed. In the context of the Italian censorship board,what was revealing was the conversation between male directors and male censorship board members about women, female sexuality, and its representation. These conversations, which were happening in the absence of women, insidiously influenced and reinforced certain social norms and collective ideas. In the performance of When The Towel Drops, I reveal the conversations behind the decisions around representation, but I also invite women to participate in – and essentially take over – this dialogue from which they were excluded.

C&: What happened to the censorship bureau? Does it still exist?

RM: The bureau is still active but without the same vehemence that it employed in the postwar period. Nonetheless, in 1998 the bureau did censor and attempt to block the distribution of the film Totò che Visse Due Volte (Totò Who Lived Twice). Thanks to public outcry the film was later released.

Radha May, Cineteca di Bologna 2014.

C&: Do you think the representation of women in Italian film, or films in general, still fits into obvious moral or political patterns?

RM: I tested different ways to circulate the material I found during the research for When The Towel Drops. I wanted to know whether ideas around gender and women’s sexuality had changed since the 1950s and 1960s and whether the scenes that were once censored were acceptable now. My first attempt at broader distribution was to use YouTube. Many of the scenes that I uploaded were flagged – reported as inappropriate by users – and subsequently taken down or age-restricted on the platform.

C&: Women’s bodies are still under surveillance, exploited, threatened, and assaulted. Sexual harassment of women, as spectacularly demonstrated in the film industry in the USA, is a serious social problem. What are your views on film, sexual freedom, and women’s liberation today?

RM: Certain harmful attitudes and behaviors, particularly around sexuality and gender roles, have been normalized through a long history of reinforcement. Using my research, I endeavor to reveal the systems that contribute to this. Because I share widely what I find, I always ask myself what it means to circulate into the public domain and memory that which was once hidden. Can the findings be used as a measure of change? Can it make a difference? Does it even matter?

C&: What is next for Radha May?

RM: I am answering these questions from the Records Center at the National Archives of India in Jaipur, Rajasthan. I have been looking at files relating to cinema censorship in India from 1951 to 1983. Although the Indian experience is vastly different from that in Bologna, very similar patterns of censorship and the justifications for doing so are emerging. This research will culminate in the second volume of When The Towel Drops. The first volume was recently featured in the show What Can be Seen, curated by Natasha Becker, at the Spring/Break Art Show in New York City (March 6–12, 2018).

Natasha Becker is an art historian and curator from South Africa.

from

Feature

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

from

Film screening

On History and Fiction: Tuan Andrew Nguyen's Cinematic Memory Work

Lebohang Kganye Awarded Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2024