The Politics of Form and Materiality

C&: Did you have an artistic childhood? Ibrahim Mahama: Storytelling was a very big part of my coming of age – there was a certain sense of freedom in inventing limitless tales, whether or not they were true. I spent most of my childhood in boarding school and I think that experience helped me to grow creatively. This made me want to see and …

C&: Did you have an artistic childhood?

Ibrahim Mahama: Storytelling was a very big part of my coming of age – there was a certain sense of freedom in inventing limitless tales, whether or not they were true. I spent most of my childhood in boarding school and I think that experience helped me to grow creatively. This made me want to see and experience great things as often as possible. With time, I think this idea of greatness has become more and more sublime.

C&: You mainly work with jute sacks initially used for cocoa and transform them into large-scale installations. Can you tell us about your intentions behind this concept?

IM: Jute sacks are not the only materials I work with, though it might seem that way during this period because of my Occupations series and other experimentations, but I am as strongly interested in them as in any other material I am quietly working with. I am mostly interested in commonplace materials and objects that have acquired history over time, and re-appropriating them. The re-appropriation is done purely with political intent, so spaces, including labor, become very crucial in the realization of most of my projects. Specifically, jute sacks used in the transportation of cocoa are very loaded with historical and modern-day narratives. Looking at them closely begins to reveal certain things about our society and our ways of living.

Ibrahim Mahama, Civil Aviation, Airport. Accra, Ghana, 2014. Courtesy of the artist

C&: You install the jute fabric that you transform in spaces like marketplaces, but also drape it on public buildings and institutions such as schools or museums. What do these kind of installations in public spaces mean to you? How do you choose specific sites for your installations?

IM: Collaborations became important in my work during one of my first installations. The input of the people who already occupied the space that I also wanted to occupy made me sensitive to the spaces around me. I am interested in interrogating materials and spaces that have significant histories and trajectories. I like to think that these characteristics of the materials are more political than purely aesthetic in their form, though the work does take on interesting forms. The materials’ studio processes have long histories that extend far beyond their origins and myself, the artist. For me, part of the work has already been done before I collect the materials. The act of collecting those specific sacks and sewing them together is important to the work’s display from one space to the other. Politically, I like to give people who might know nothing about my art, but share somewhat in its conditions, the chance to assist me in configuring the work. New ideas are readily accepted as the conditions of the site determine how the piece is going to be displayed. The space’s function is relevant to the installation process. Nothing is to be taken out of the configured spaces. The works take the form of the concrete space and the objects within it, but still allow the spaces to function as if the intervention had not been made, as if the artwork were not there. I choose specific sites based on their form. The autonomous power of art is broken, from its creation to its display, as people negotiate their way through it and their relationship with the process of making the artwork and its final display throughout. The presentation challenges conventional gallery and museum presentation and classification strategies; these projects interrogate the “white cube space.” Certainly this draws on influences such as Santiago Sierra and minimalist art.

C&: Acclaimed artists such as El Anatsui, Yinka Shonibare, Sonia Delaunay, and Abdoulaye Konaté work and have worked with textiles and textures in their own particular ways. What does the use of textiles in your artistic practice mean to you?

IM: Textiles are a very important part of our history. I first became interested in them came to the realization that I was generally interested in the state of things and that’s why I was drawn to them. They are an archival document for me, documenting the accumulation of time, history, form, and place. There are different moments in there I cannot quite grasp, and I became interested in experimenting with those intersections to extend pre-existing forms or create possible new ones. Another thing that also drew my interest was the idea of textiles containing forms and now having to interrogate forms larger than my original ideas for my work. The politics of form and materiality within this context helps me to understand and constantly push my interest in this area. It is an ongoing process.

Ibrahim Mahama, K.N.U.S.T Library. Occupation and labour. Kumasi, Ghana, 2014. Courtesy of the artist

C&: You are based in Tamale/Accra and also work internationally in cities such as London, Dakar, and now Venice. Through all these travels and experiences, how do you perceive the Ghanaian art scene?

IM: A recent exhibition like Silence between the Lines; Anagrams of Emancipated Futures is a really good point to start from. The Ghanaian art scene is currently going through a lot of changes but it’s always been very promising. The Painting and Sculpture Department along with other artists at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology (K.N.U.S.T) in Kumasi has put in a lot of work to bring the art scene where it is today. Compared to other centers for artistic discourse, the department doesn’t have the necessary structures in place, but I think that is what makes it really exciting. Lecturers constantly push artists to think about how they can position themselves within different contexts to bring about changes, which have heavy implications for the art world. It is a very slow and carefully thought process, which needs time and the right steps. But it’s very inspiring and humbling especially when certain players within it have dedicated their entire lives to this.

C&: How do you see your role as an artist?

IM: Society has always defined roles for different people based on their abilities, position, and reasoning, but I believe in working together so there can be better structures in place. The current state of Ghana and the continent at large serves as a compelling reason to act as more than just an artist, but a socio-political and cultural player. Urgent issues need to be addressed and I believe the time is right.

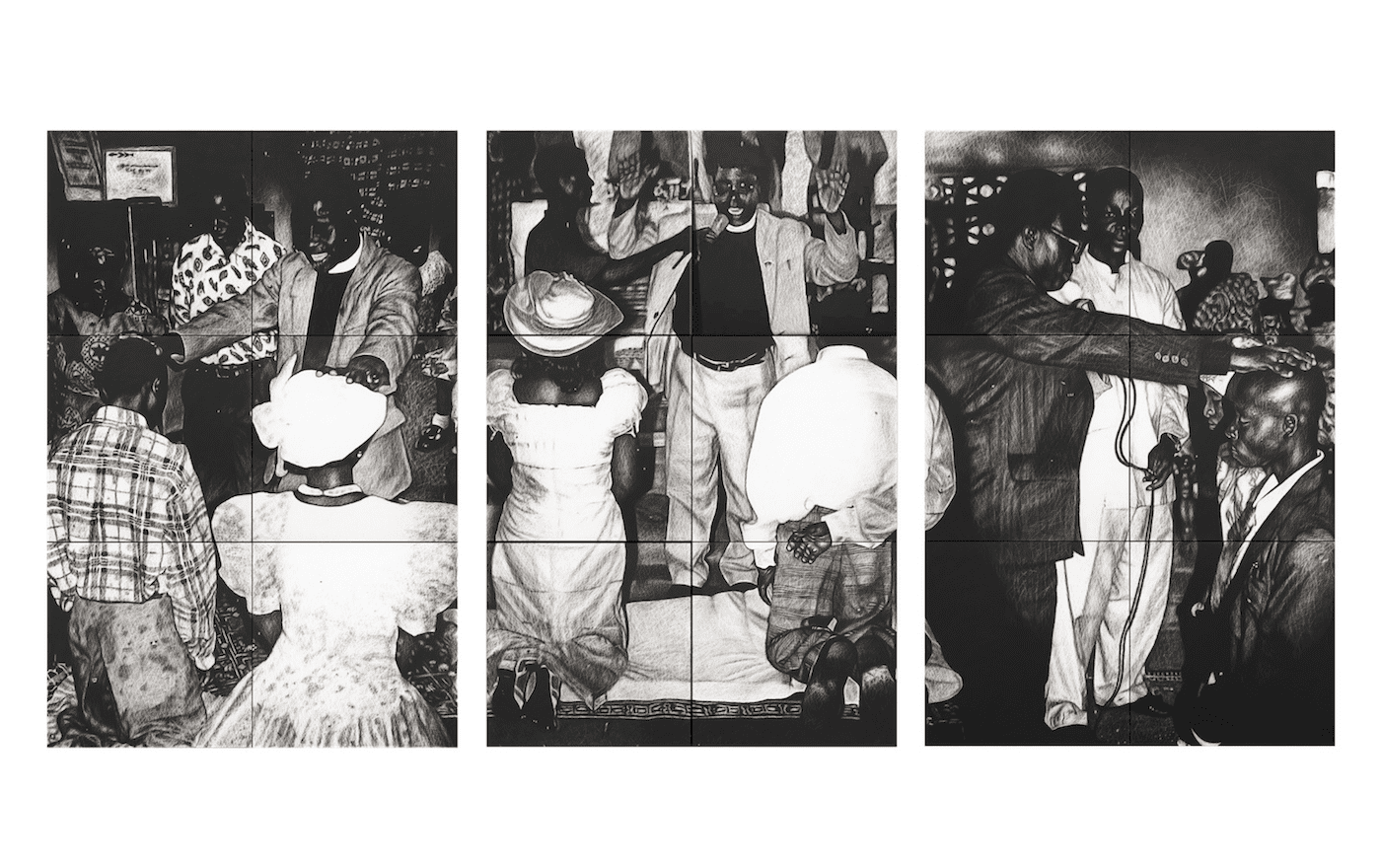

Ibrahim Mahama, “Samisa Towers of Emancipation. Silence Between the Lines.” Group Exhibition. Kumasi, Ghana, 2015. Courtesy of the artist

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

Installation

Syowia Kyambi: Kaspale

Igshaan Adams: Kicking Dust

Namibian Pavilion Debuts at 59th Venice Biennale

Ibrahim Mahama

ART X Lagos Announces Theme and Program for 2023

Ghana Exchange Program “Travel Somewhere Nice” Launches Second Edition