Soweto Story

23 June 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min read

In the series Curriculum of Connections, we bring together critical voices, ideas, and projects working towards educational, artistic, and research practices. In this space, we learn, unlearn, and co-investigate old and new territories of knowledge systems, collaborations, and imagination. These are three ways in which the students who participated in the 1976 Soweto Uprising have …

In the series Curriculum of Connections, we bring together critical voices, ideas, and projects working towards educational, artistic, and research practices. In this space, we learn, unlearn, and co-investigate old and new territories of knowledge systems, collaborations, and imagination.

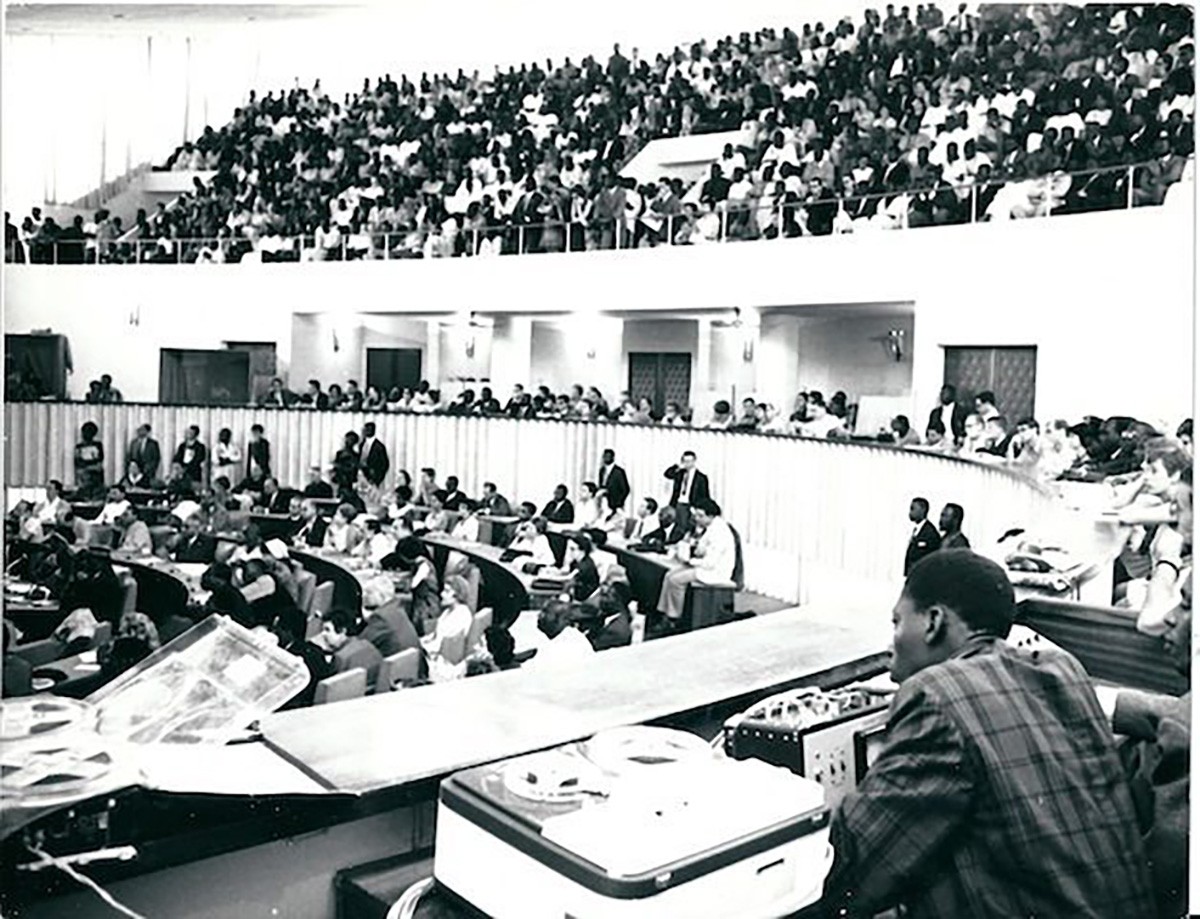

These are three ways in which the students who participated in the 1976 Soweto Uprising have been historicized. In a nutshell, the Soweto Uprising took place in 1976, when the apartheid regime introduced the Afrikaans language as a medium of instruction in Black schools. Most narratives of the Soweto Uprising begin with the march by students on 16 June 1976. On that day, students from a number of schools in Soweto organized a march through Soweto in protest. The march started peacefully, but at some time that morning, police opened fire on the students, killing many, including twelve-year-old Hector Pieterson. The students retaliated by burning and destroying property and facilities that they associated with the apartheid regime.

The violence quickly spread to other parts of the country as thousands of students rose in defiance of the apartheid regime. By the end of December 1976, close to 600 mostly Black youth had been killed, thousands had been arrested, and others had gone into exile and joined the liberation movements and their military operations.

Following media reports of the Uprising students, they almost immediately became symbols. Accompanying the images of pain and anguish, there was a tendency to frame the students in religious terms. Words such as martyrdom and sacrifice have been periodically used. Perhaps the idea of redemptive suffering was important to make needless deaths seem more heroic and to galvanize resistance against the state. However, I think it is important to remember that although some of those students had consciously planned and took part in the protests, many others were killed indiscriminately. To my mind at least, the idea that the students were a necessary sacrifice in order to attain freedom speaks more to the battle of religious ideologies than to the students’ understanding at the time of what their actions were supposed to achieve.

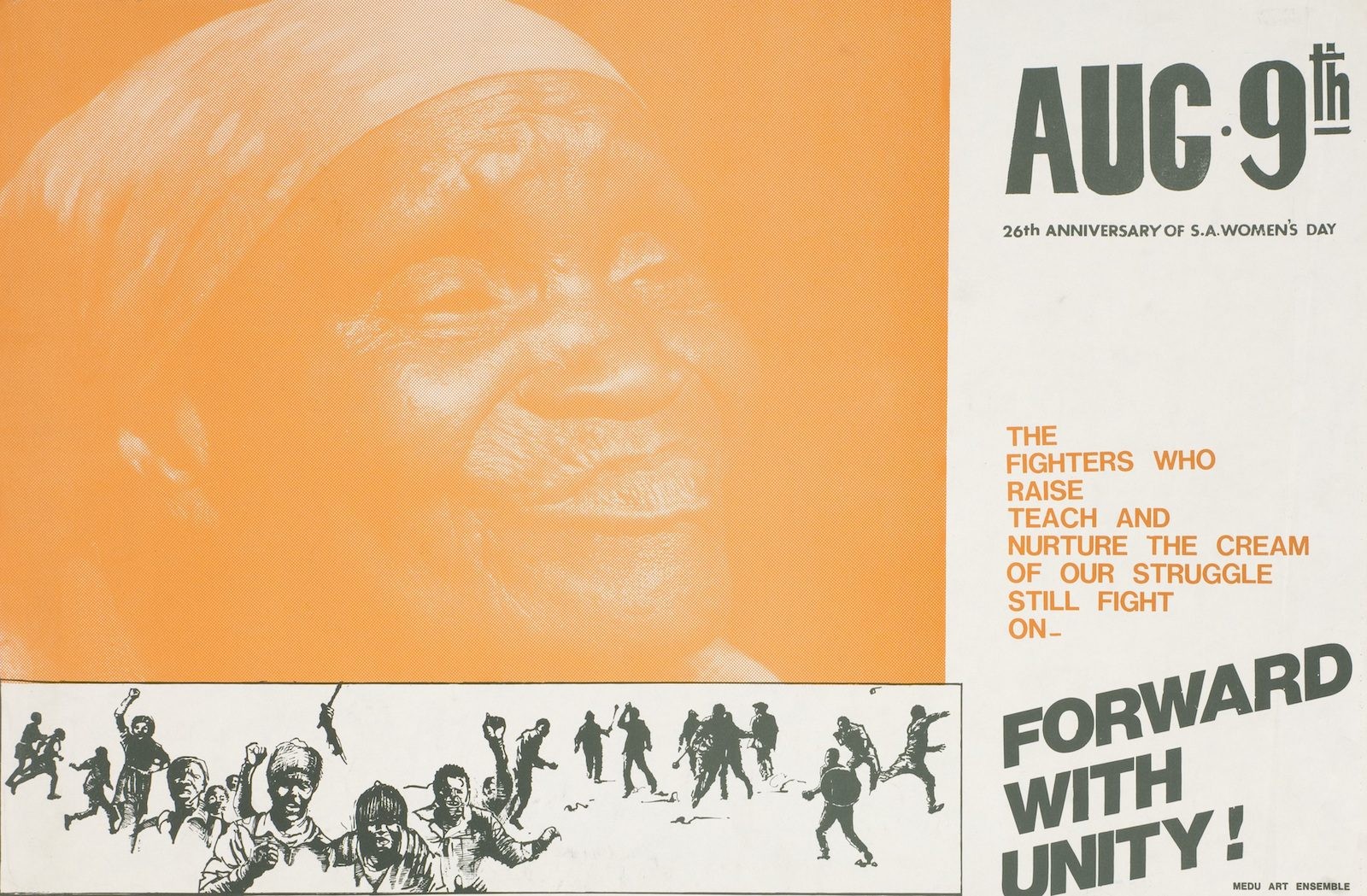

Medu Arts Ensemble, Forward to Unity (c. 1980–85), Screen print on paper. Courtesy of Medu Arts Ensemble.

There were also excesses such as the killing of Dr. Edelstein on the same day. Several liquor stores were destroyed that day and looting took place. The justification for this action has generally been that liquor had become an opiate of the oppressed that prevented Black people from resisting apartheid and confined Black people to accepting their fate. But we must also think about what is implied in the act of not just looting liquor stores but attacking other delivery vehicles. Was this just simple criminality, as some – including Black people – would have argued in those days? Or was it a kind of rudimentary economic warfare? Images of looting do not sit comfortably with narratives of heroism and sacrifice and generally get left out and ignored. But I think these images should be resuscitated – not to demonize the students, but to enable a more complete understanding of the repertoires of struggle. Neither deifying nor demonizing properly locates the actions and thinking of struggling subjects in historical, political, and everyday realities, where strategy and contingencies cannot be separated into neat categories. And ethical boundaries are not always clear, especially when dealing with a regime that is impervious to more peaceful means of resistance. Its symbolic power exceeds the limits of the images which represent it. Now that history has vindicated the students of the events now known as the Soweto Uprising, it is easy to forget that at the time of the Soweto Uprising, many people found the students’ actions scandalous or highly inappropriate.

As many observers have argued, the events of the Soweto Uprising were significant in several ways. But one way is that this was the first time that students, youth, or children – depending on your outlook – were thrust into the forefront of the anti-apartheid struggle. The state’s brutality of the state towards children was shocking, but the students’ violent reaction also came as a shock. It must be remembered that although certainly youth culture had begun to emerge as a force in Black communities, the prevailing ethos was deference to one’s elders.

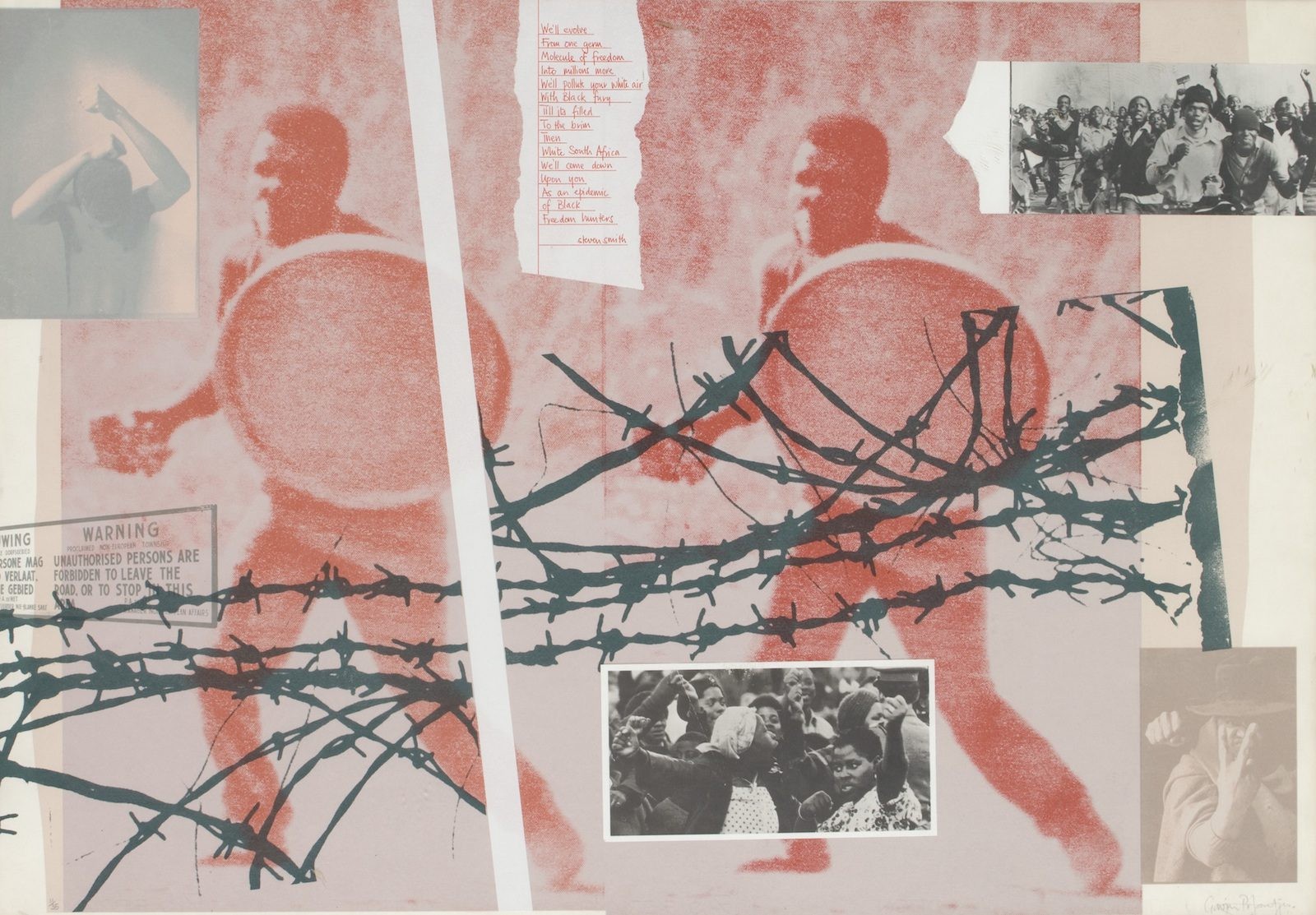

Gavin Jantjes, A South African Colouring Book (1981), Screen print on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

It would be extremely tempting to draw parallels between the students of 1976 and the current Fees Must Fall and Rhodes Must Fall Movements. The two situations are hardly comparable, if for no other reason than the fact that the Fees Must Fall Movement, unlike the student urprising of 1976, is taking place in a democratic dispensation. The present-day student movement is able to invoke the memory of the 1976 generation precisely because of its symbolic power. At the same time, it has been remarkable how large sections of society, many of whom might have participated in the student movement of yesteryear, have condemned the Fees Must Fall protests – in part due to their irreverent stance towards authority. And so the language that characterizes students as thugs and criminals has returned to the everyday lexicon. Some have gone as far as to claim that students are under the sway of foreign agents seeking to destabilize the state.

Although history seems to have vindicated the generation of the 1976 Uprising, these tropes have survived to the present day. Indeed, large sections of the South African public are very divided over how to characterize the current student movement. The overriding factor in all these versions of who and what the students were seems to rely on archetypal images mobilized by the different sides of the discourse to different political ends. And in the contest to win over public opinion, the contingencies in the arena of struggle will always exceed the symbols that only serve convenient but limiting ways of understanding historical contexts and processes.

Khwezi Gule is a curator and writer based in Johannesburg. Gule is also Chief Curator at the Soweto Museums, which includes, the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum and the Kliptown Open Air Museum. He writes here in his personal capacity.

.

This article was first published in the latest C& Print Issue #7. Read the full magazinehere.

Read more from

Black Canadian Print Cultures: Of Quiet and Enduring Legacies

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

A Call to History

Read more from

Rest in/as Freedom: kiarita and Black Politics of Liberation

Not for Sale: How Black and Indigenous artists are rewriting the rules of the art market