Shaping the Bigger Picture

17 May 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min read

Wary of an art scene that seems to be always looking outside of itself (and mostly to the Global West) for recognition, and deeply cynical of government involvement in art programs, Jimmy Ogonga, curator of the Kenyan Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2017, met with me for an interview. Named after one of James Baldwin’s …

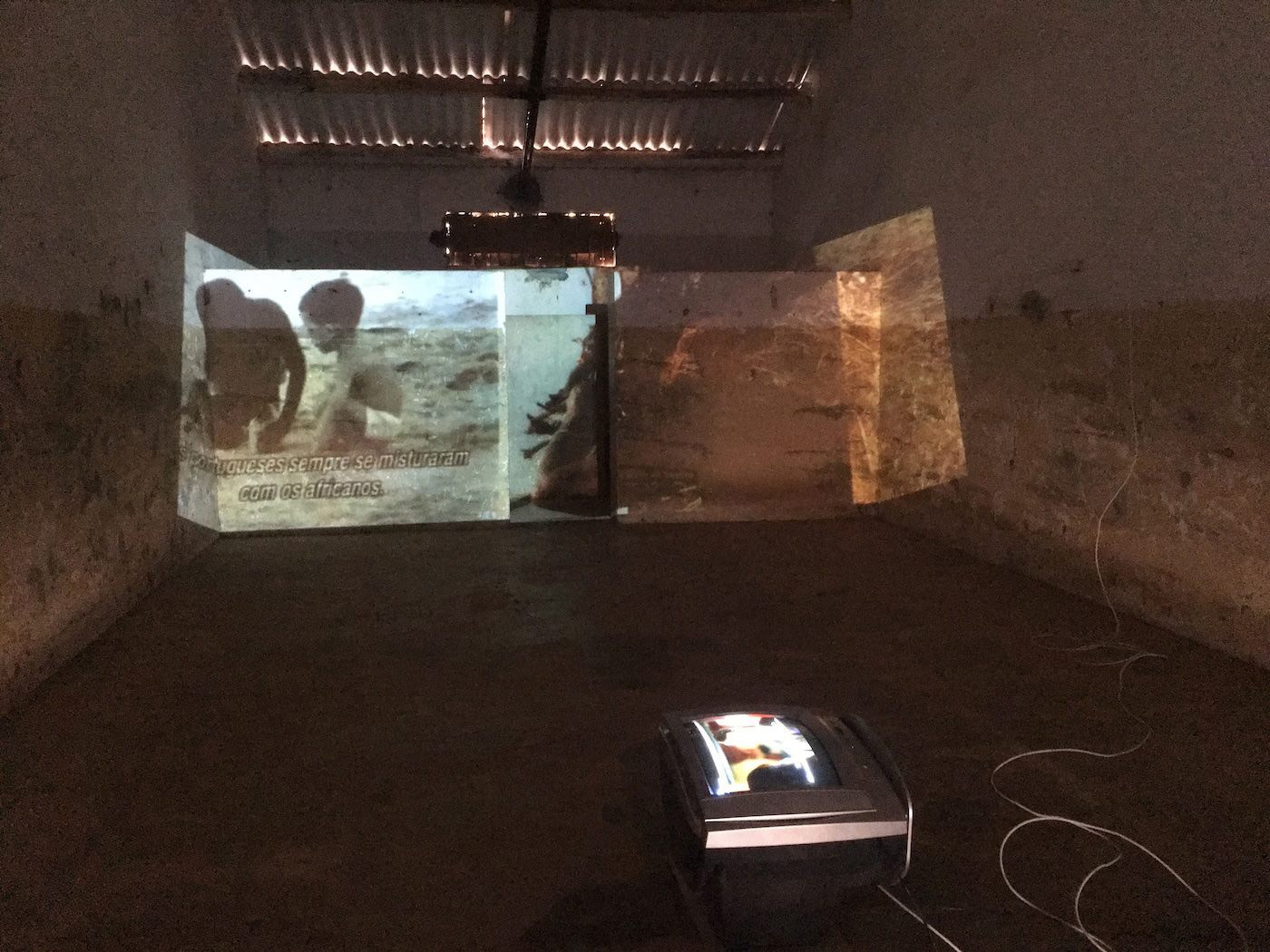

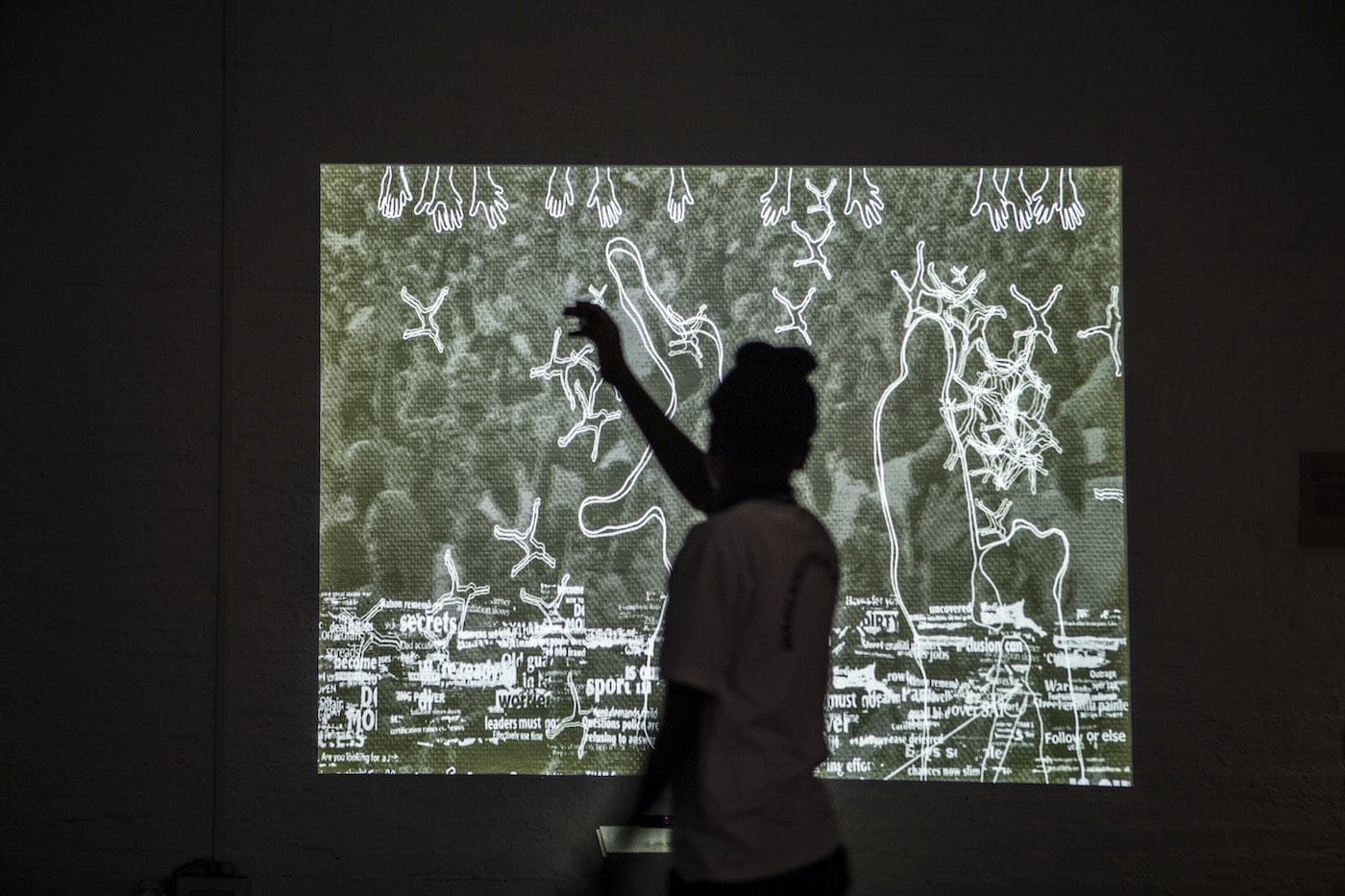

Wary of an art scene that seems to be always looking outside of itself (and mostly to the Global West) for recognition, and deeply cynical of government involvement in art programs, Jimmy Ogonga, curator of the Kenyan Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2017, met with me for an interview. Named after one of James Baldwin’s books, Another Country, the pavilion is going ahead in spite of the government’s reluctance to release funds for it in time.

Awuor Onyango: Could you please give us a brief history of how you came to curate theKenyan Pavilion?

Jimmy Ogonga: In short, the cabinet secretary of the Ministry for Sports, Culture and the Arts nominates the commissioner and the curator. The curatorship for the 2013 and 2015 pavilion was awarded to Armando Tanzini, who included twelve artists, most of them Chinese. In 2015 there was an outcry, mostly by artists in Nairobi who felt it was not representative.

AO: Did you already have a plan to curate the pavilion in 2013 and 2015?

JO: Yes, we actually had a proposal for Venice in 2013 and submitted it to the government, but it didn’t reach the right people – or Tanzini had better connections. In 2013 local artists were willing to take part in this platform. This should have been the determining factor, instead of choosing someone who may not have the right intentions.

AO: In your opinion, what does displaying Kenyan artwork at Venice have to do with cultural and artistic production within the country?

JO: It is important for good contemporary art to be shown in Venice, a high-level international platform that validates and provides a much-needed push for artists’ careers. Having a national pavilion has obvious repercussions in terms of art history, access to international markets and audiences. It is a statement of seriousness from both the artists and art institutions, as well as from the government.

AO: Does participation in the Venice Biennale have any influence or repercussions in Kenya?

JO: What happens when a country manages to take part be in the World Cup or the Olympics? Just like the World Cup, Venice is a huge international event. Look at what happened to the Zimbabwean artists and the national Zimbabwean art scene after participating in the four editions of the Zimbabwean Pavilion. My feeling is that once you are present there, more people will be interested in the local art scene, artists might be invited to more international events. We are talking about exhibition catalogues as knowledge conservatories; it’s like being plugged into the international contemporary art scene. That is why the repercussions are obvious to me. However, the individual artist’s career will depend on him or her – let us not think that this pavilion will work miracles for all Kenyan artists.

The exhibition Magiciens de la terre was very distant from me when it happened in 1989 [at Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle at the Parc de la Villette in Paris], yet still, although it was not designed to benefit me directly, it started a very important conversation for me as Jimmy Ogonga. Repercussions can be complex – we can try to anticipate them, or have the conversation retrospectively.

AO: Why James Baldwin, a queer Black icon whose work is steeped in his queer Blackness?

JO: I think we need to separate the artist from his work. I would rather talk about the work than the artist.

AO: The work in this case being Another Country. How does it play into the pavilion?

JO: The book is clear – it is a tragic narrative about eight characters who live in difficult and unforgiving times.I use Baldwin’s narrative and the artists’ work to see what other narratives come up. Baldwin stood for something. He was able to formulate something both a scholar and the man on the street would understand – an interesting mix of a scholarly and non-scholarly disposition to look at society. In Kenya, contemporary art does not have the necessary educational infrastructure to be able to decode or unpack a lot of the things that we are talking about or are dealing with as a society.

Baldwin also had the ability to speak to power in a critical, emotionally balanced way. He spoke critically to the Black people, to the white people, to the liberal, the queer community. He spoke critically to all these people without pushing them away.

This book, Another Country, and the work by the artists in the Kenyan Pavilion give us a rich reading of the society we are experiencing at this point in time. If you add in Christina Macel’s revolutionary theme for the art show, Viva Arte Viva, we have the opportunity to see the power of art.

AO: How does this reflect the state of a country which identifies more as African than Black and, quite frankly, doesn’t recognize queers as part of its population?

JO: When we are talking about Baldwin’s queerness, it is important to understand that I don’t describe him as queer, and when setting up the pavilion we did not focus on sexualities in providing certain opportunities. It is not really my objective in the exhibition to comment on the issue of queers in Kenya.

AO: On that note, Simon Njami, who in turn identifies as Black but not as African, is listed as an advisor to the project advisory role. How did this come to be?

JO: Simon Njami is Simon Njami. Revue Noir, one of Simon’s earlier projects, included an anthology of African and Indian Ocean photography. A number of writers and photographers came to research in Kenya and East Africa, creating context about photography in Kenya in the early 1990s. It was the first time that I saw anyone writing about photography in Kenya from that perspective. He was invited by CCEA (Nairobi) as artistic director of Amnesia, running for about six years with workshops, exhibitions, publications covering a population of artists from Nairobi and from different parts of the world.

AO: Does the list of participating artists comment on art or artistic practice by female artists in Kenya?

JO: I cannot use the artists/artwork in the pavilion to tackle this issue. It is a question that is not part of this process, a question for somebody else to look into.

AO: How have you dealt with or negotiated the cynicism in the process of producing the pavilion?

JO: By working, preparing, and doing everything that needs to be done. We have managed to get commitment from friends in Venice, and although the Kenyan government has not provided us with any money we are going to have the Kenyan Pavilion.

Awuor Onyango is a writer, artist, filmmaker and photographer with a wide interest in different media, whose work explores self-perception, individualities, gender, art and cultural histories.

Read more from

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Read more from

Flowing Affections: Laryssa Machada’s Sensitive Geographies

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?