Serine Ahefa Mekoun Dives into the Wisdom and Validity of Works of Art

Our author highlights the inspiring artistic positions of this year’s documenta that took place from 8 June to 25 September 2022 in Kassel, Germany.

When certain aspects of an image or narrative are erased, what is left in the frame and what is put outside it? What types of stories emerge when parts are isolated? Because of the heated debates around accusations of antisemitic images at this year’s documenta, many artworks and critical positions encouraging discussions and counter-narratives were hardly noticed. Now that documenta fifteen is over, this text recaps some of the works exhibited in Kassel.

With an eye to posterity and in the spirit of lumbung*, it is essential to separate the wheat from the chaff and to dive, without further ado, into the wisdom and validity of the ideas that all of these artists entertain and the projects they undertake—not only locally but on the African continent as a whole. ForLumbung I (documenta 15)* also prominently featured Ubuntu (South Africa), Mkhazen (Algeria), Maaya (Mali), Letsema (Lesotho), and Bulungi Bwa'nsi (Uganda) … They all have a close relationship with lumbung* and are witness to the African continent’s long, rich artistic and social heritage, whereby the members of a community help each other by sharing resources for projects in the areas of education, construction or agriculture … From Algiers to Johannesburg by way of Bamako, these philosophies of life going back thousands of years were embodied and activated right through the documenta gathering by some fifteen collectives and artists in concert with other communities on the international scene (lumbung-interlokal*), who modeled their artistic practices and ekosistems* on these interdependent mechanisms.

<figcaption> The Nest Collective. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

Art for real life: connecting with major issues of national policy

Many artists are using the language of art to echo the national struggles that are in the news and to condemn or help drive major sovereignty issues relating to land and the environment. The forms employed to put the message across have taken a turn that is not just architectural but also poetic: one good example here isThe Nest Collective (Kenya) with its installation comprising bundles of used clothing (Return to Sender). It is a direct reference to the talks that have been taking place for several years between the United States and five East African countries (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda), who have come together around a joint plan to ban the import of waste from the textile industry, dressed up as second-hand clothing (mitumbas).

<figcaption> Madeyoulook. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

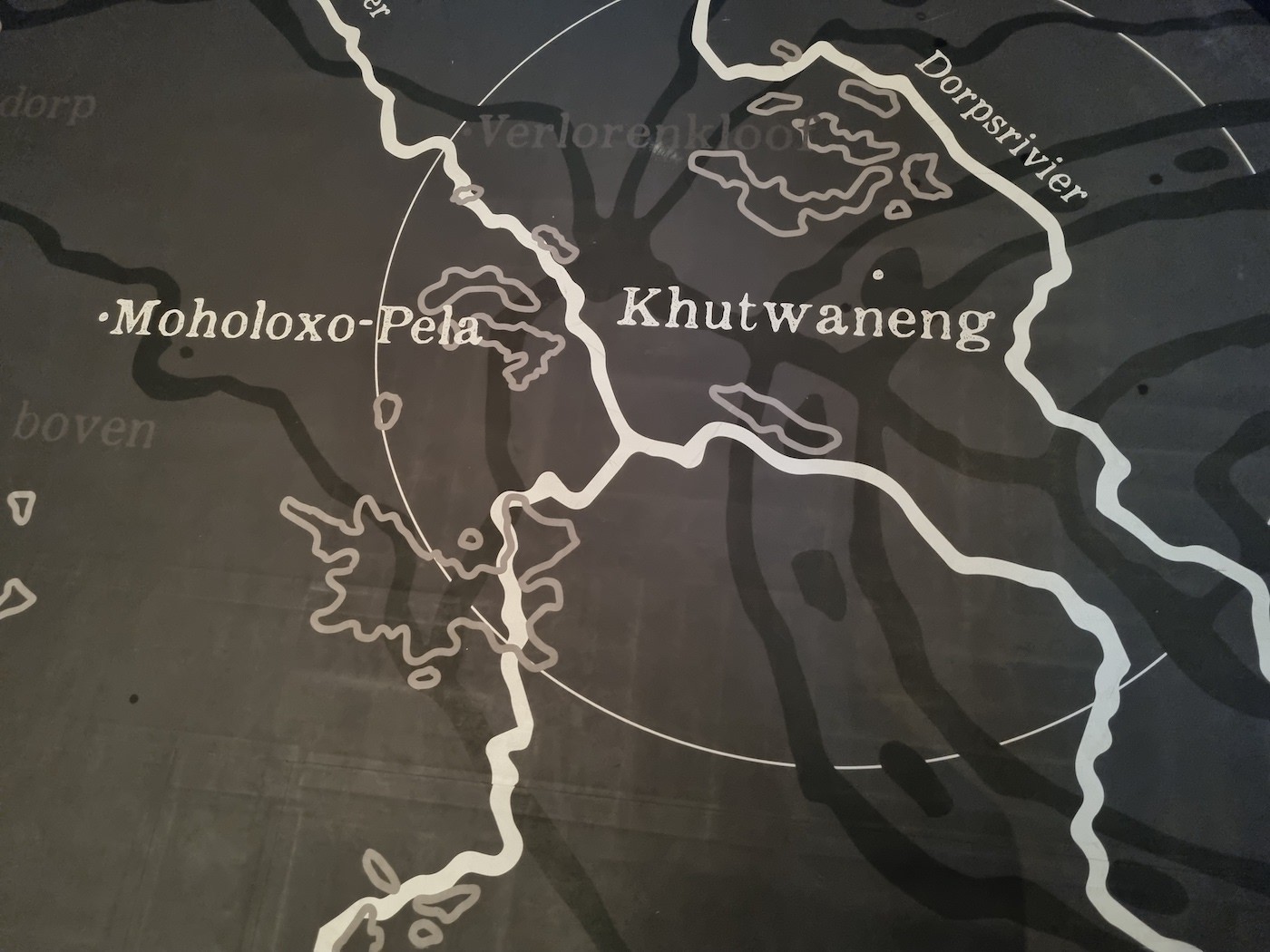

The sound installation (Mafolofolo) and gardening workshops byMadeyoulook (South Africa) likewise forge an extremely sensitive connection to the struggles surrounding the redistribution of land to the black people who were victims of the 1913 Land Act that legitimized the appropriation of land under apartheid, a situation that persists to this day. Meanwhile,Keleketla Library’s work in the context of Skaftien, a project focused on promoting community culture in Johannesburg, demonstrates how data obtained as part of a process of artistic research can be actively reused in strategic negotiations. In this case, for the purpose of lobbying various governmental actors in South Africa to create a center of arts and culture by refurbishing the Drill Hall, a military barracks built in 1904, which was used as a courthouse during the proceedings against 156 anti-apartheid activists on trial for treason.

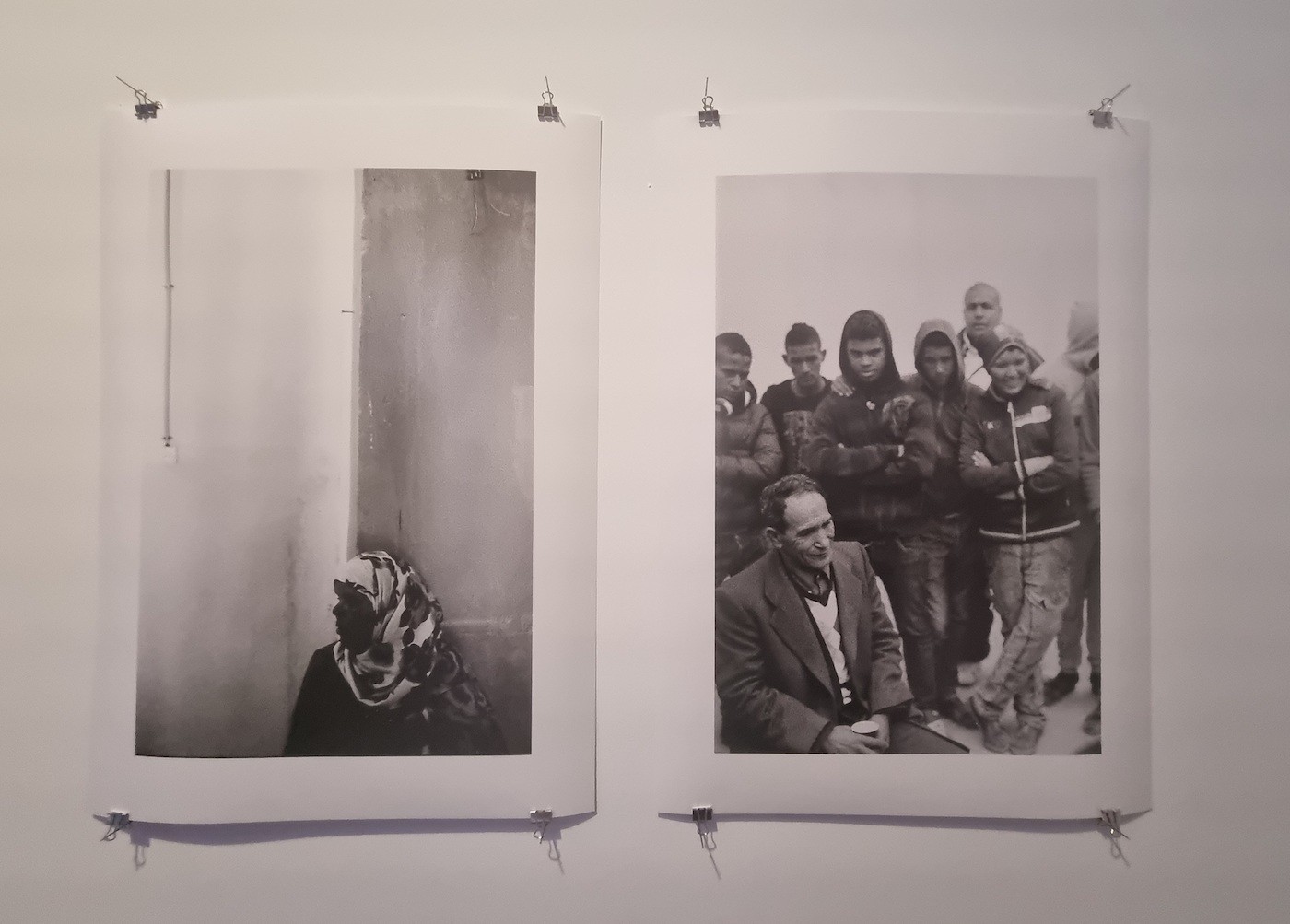

<figcaption> ARAC. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

Art as a place where everyone can put their knowledge into practice

TheARAC pan-African network’s Schoolbook Project with its series of booklets and its focus on practicing education through art from a decolonial perspective is a counterpoint to the “off-site” versions ofEl Warcha (Tunisia) andWakaliga (Uganda), which highlight the action and art of DIY. An ideal place in which to research practice-centered educational methods, the El Warcha collaborative design studio invites people to take part in traveling construction workshops where they can get out of the role of consumer or spectator and create prototypes involving the recycling of materials and furniture put to whole new uses.

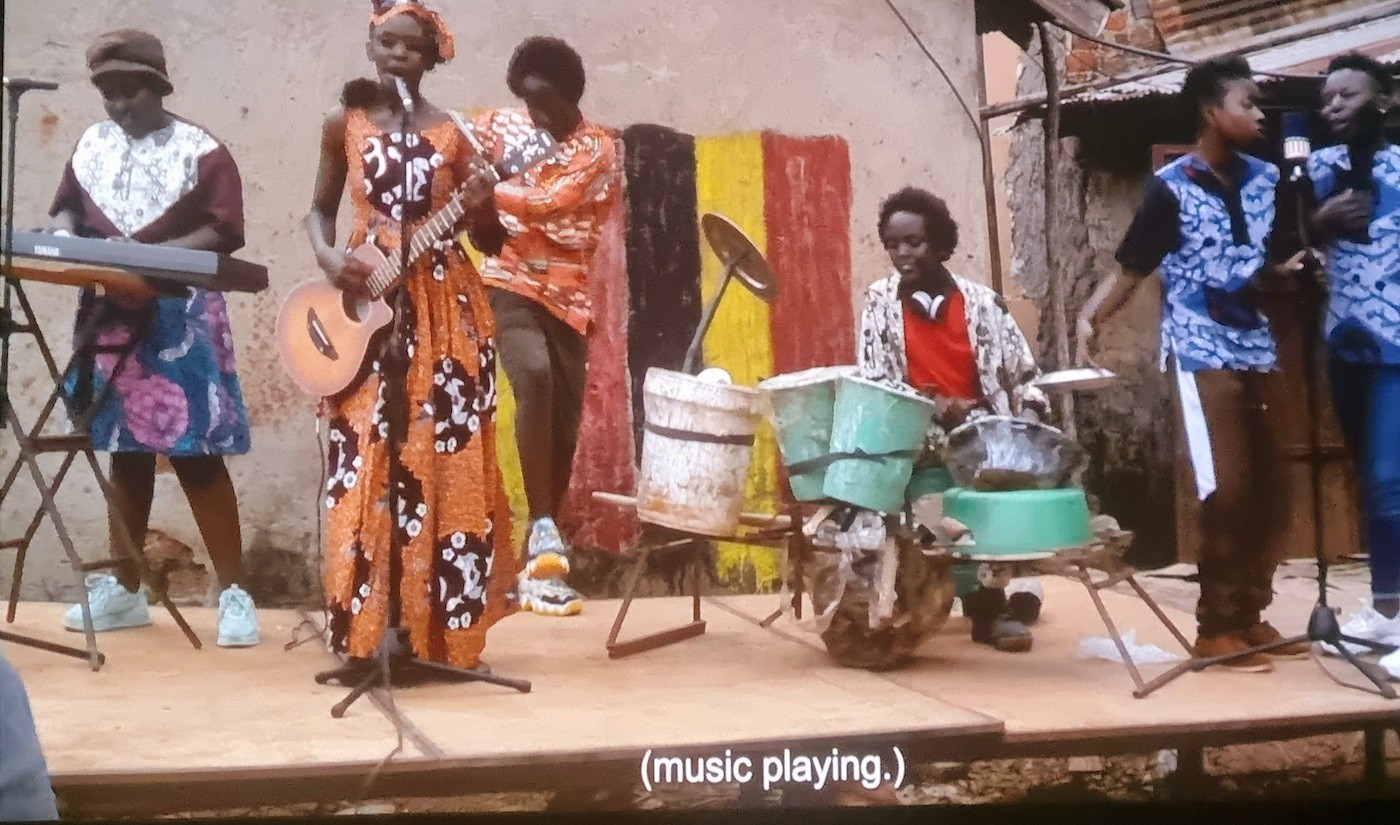

<figcaption> Wakaliga, Screenshot. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

Drawing on the same organic spirit, the action films made by the Wakaliga film studio, which is based in a slum in Kampala, are testament to a cinematic ecosystem in which films are made by and for the local neighborhood. The focus is on articulating a critical yet entertaining view, raising the awareness of entire generations to the importance of “playing” and sarcasm: the films depict the violence of a social reality that is the object of scorn and offer condemnation of a political regime whose abuses have an alienating effect.

<figcaption> Archives des femmes en Algérie. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

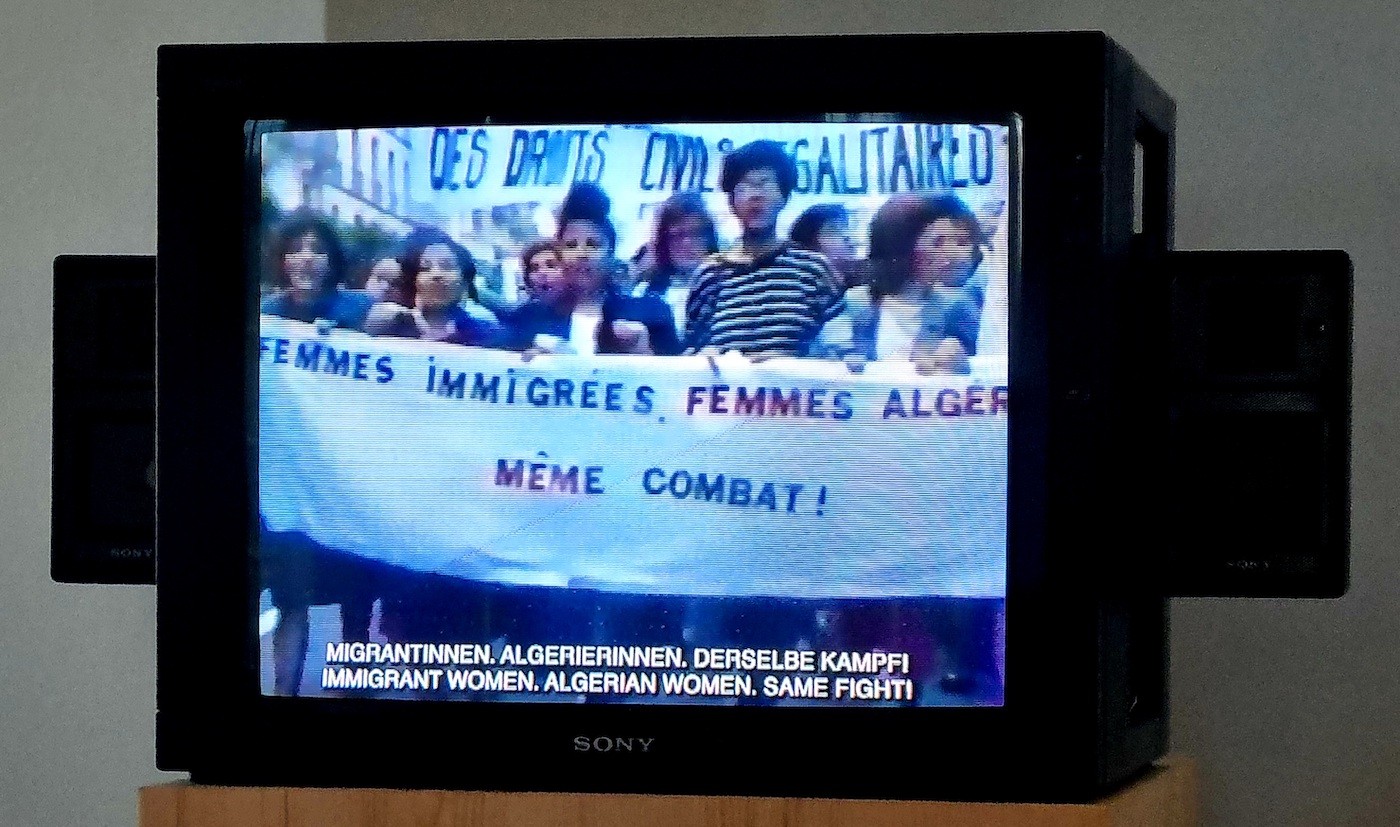

Archives as poetic tools for voicing struggle

Popular platforms of circulation, such as free digital archives, alternative radio stations, and underground cinemas, are essential means of transmission in the jumble of awareness that is censored or anesthetized by a propagandist media culture, resulting in a program of misinformation. TheArchives des luttes des femmes en Algérie (Archives of Women’s Struggles in Algeria) is committed to weaving intergenerational links by drawing on a forgotten feminist past: its open-access digital platform, which was launched in 2019, is a collection of archives focused on campaigns for women’s rights and gender equality running through the history of modern-day Algeria.Le 18, a multidisciplinary cultural space based in Marrakech, seeks to use the image as part of a project of decolonization—mediated by, among other things, the restoration and dissemination of film archives.

<figcaption> SiWa Art plateforme. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

Siwa Plateforme from Tunisia sets out to make decentralized stories audible using the sound archives of the people of Redeyef, which was a center of phosphate mining in the colonial period and has now been transformed into a laboratory for artistic experimentation. Wireless technology as a tool for broadcasting in revolutionary contexts also has a long tradition in South Africa: emblematic of this is the Chimurengaradio station, which has sought to promote pan-African broadcasting by making the audio resources of anti-colonial liberation movements available via a network of affiliated radio stations.

<figcaption> Wajukuu. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

Art and local culture as instruments of social and economic regulation

For many countries on the African continent with precarious economies, humanist concepts form the basis of their model of cultural entrepreneurship and local development. Their privileging of the relationship between the individual and the community make these systems an integral part of endogenous mechanisms designed to prevent conflict and regulate the functions of society. One example of this is theWajukuu Art Project, a Kenyan artists collective whose name in Swahili expresses the responsibility of the elders to care for the next generations. Wajukuu uses art and the revenue it generates to get young people out of crime.

<figcaption> Waza Art. Installation view at documenta fifteen. Photo: Serine Mekoun

Based on a kindred sense of situational intelligence and the generous presentation of symbolic acts and objects (puppets, traditional clothing, performances, etc.), theFondation Festival sur le Niger provides an introduction to the values of the Maaya and to the principles underpinning the Kôrêdugaw communities, Mali’s initiatory societies that maintain the country’s wisdom rites and guarantee the transmission of knowledge to the following generations. Lastly, the DRC’sCentre d’art Waza takes a fresh approach to the issue of tourism and considers ways of integrating it into the preservation of the artisanal heritage of the traditional villages in the province of Lualaba via a network of eco-museums intended to provide local stimulus to involve people within the society in artistic creation.

<figcaption> Keleketla Library! Skaftien. Courtesy of the artist.

Crystallized by the sense of struggles converging, an unprecedented opportunity is emerging for everyone to gain a better understanding of how new models of sustainable cultural and artistic production can be articulated and continue to unfold in future African contexts and beyond. This involves practice, not contemplation, first by drawing on the inventiveness inherent in resilient practices that have developed out of histories of violence and abuse and of sociopolitical instability; and second, and more importantly, by tapping into a desire for liberation from financial systems that depend on Western networks of cultural diplomacy, which still have too much sway over the artistic ecosystems on the African continent and, more broadly speaking, in the Global South.

The path followed by Lumbung I was also necessary to connect different generations and communities engaged in intracontinental and diasporic practices that otherwise have trouble coming together, stymied by the tyranny of borders. It is a space-time continuum made up of intense exchanges and consolidated artistic practices that also derive their power and poetry from the pleasure of being together.

Taking a pragmatic approach that is no less poetic as a result, all these collectives have made it possible to rethink the “why of how” in art: What role does it play in real life? Who is it addressed to? And how can it be transmitted while ensuring its viability in precarious, even hostile environments?

Serine Ahefa Mekoun is a multimedia journalist, writer and producer living between Brussels and West Africa. Born at the cusp of Generations Y and Z, she is interested in all the spaces where different futures can germinate. She namely writes about creative communities and how they activate social change in postcolonial contexts.

Translated by Simon Cowper.

Lumbung glossary:

* As an artistic and economic model, the lumbung (an Indonesian term for a communal rice barn) is rooted in principles such as collectivity, the sharing of communal resources, and equal allocation.

* Lumbung I is what the Indonesian collective ruangrupa and the exhibition’s international participants called documenta 15 as the first European edition of the practice of lumbung (staged in Kassel, Germany, from June to September 2022).

* ekosistem: an ecosystem of groups and individuals in collaboration who are connected to one another or have an interdependent relationship.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission