On Arthur Jafa and the US-centrism of Black representation in Europe

21 March 2018

Magazine C&

5 min read

Whenever he is asked if he’d consider adapting one of his exhibitions to its particular location, Arthur Jafa unequivocally says no. And – aside from that being his right as an artist – he has a point. Currently Jafa has a large show at Berlin’s Julia Stoschek Collection (JSC) in partnership with London’s Serpentine Galleries, …

Whenever he is asked if he’d consider adapting one of his exhibitions to its particular location, Arthur Jafa unequivocally says no. And – aside from that being his right as an artist – he has a point.

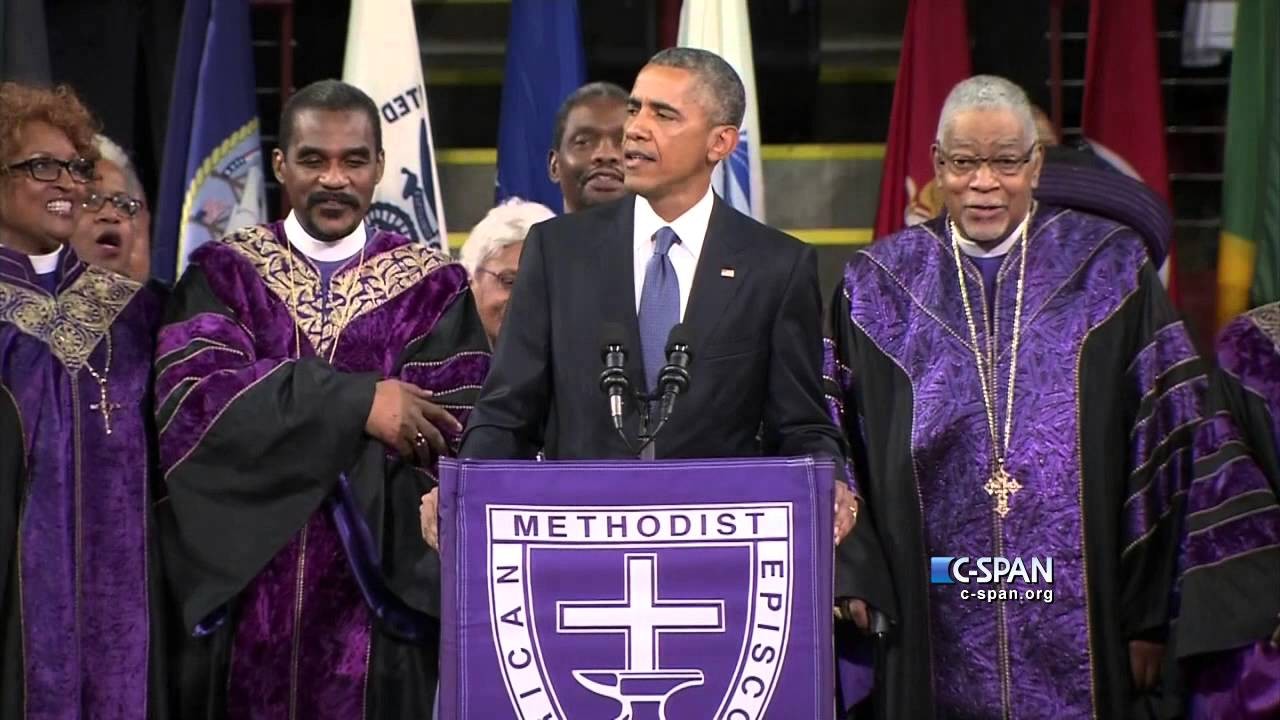

Currently Jafa has a large show at Berlin’s Julia Stoschek Collection (JSC) in partnership with London’s Serpentine Galleries, where the artist showed last year. Both iterations of A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions deal heavily with race issues specific to the North American context, in the form of intricate video montages with a cathartic quality. “I want to make black cinema with the power, beauty, and alienation of black music,” said Jafa in Interview magazine last year about Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, a video containing found footage of Black sorrow and success, arranged to Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam.

For Jafa’s work to adapt to a particular location or context, especially internationally, would mean the standardization and simplification of the Black experience. And by extension the erasure of the Black experience – in this case in Europe, where his work is being shown. However, from a curatorial point of view that’s also exactly what’s at stake when European curators give more exposure to non-European artists when curating shows that engage with race issues. In Europe, for example, the UK celebrates Black British and African American artists over Black Europeans.

Examining this kind of curatorial approach, the elephant in the room, is crucial for various reasons.

<figcaption> Photo courtesy of Makode Linde

There are plenty of Black European artists exploring and experimenting with art that deals with the complexities of being Black in the world, grounded on their experiences at home. These include Patricia Kaersenhout, Délio Jasse, Keyezua, Namsa Leuba, Makode Linde, and Babiche Papaya, to name a few. The lack of support for these artists on a large scale might be a genuine oversight, but ultimately it erases these stories and art forms that are much more relevant to Europe, especially at a time when the far right is regaining ground. Historically this is what has happened: White people in Europe (especially continental Europe) support the struggles of African Americans while ignoring the struggles of Black Europeans. And naturally the same paradox reproduces in art.

This disconnection can be much more insidious than at first inspection. Black people are not appreciated the way Black art is; and art by Black Europeans is not appreciated the same way as art by African Americans. By extension the realities of Black people in Europe (whether European or not) are omitted.

Historically, white curators’ call of defense is that these artists (who deal with race or do not) are simply not good enough. But plenty of examples demystify that claim. For instance Julia Phillips, who has an upcoming solo show at MoMA PS1, is German. And actors Boris Kodjoe (Brown Sugar) and Florence Kasumba (Black Panther) are also German. Perhaps their strategy is to hide their Germanness so that they can be acknowledged in Germany at a later stage of success.

One great pitfall of this curatorial ability to otherize art that deals with race, and instead fetishize its formal greatness, is that it gets easily tokenized. That way the subject matter becomes something almost abstract and distant, which is what happened at the Jafa opening in Berlin. There, some of the white guests who claimed to be engaging with the art weren’t aware that it’s not OK to touch Black people’s hair – odd given that Jafa was the director of photography in Solange’s video for Don’t Touch My Hair, a song about that exact point.

For an African American artist to have two major debut solo shows in Europe in the same year is laudable without a doubt. Yet it still has to be asked why these same institutions have considerably less interest in Black European artists who also deal with race. British artist Isaac Julien has been previously shown at JSC, and the Serpentine is currently showing the work of African American Sondra Perry. But Julien, for instance, does not deal with race in the same direct and open way that Jafa does, which begs the question of whether this is the only way that Black artists in Europe can get support from big institutions – by steering clear of race.

Similarly, when discussing these curatorial choices certain questions have to be answered about the reasons for wanting to show Jafa’s work in Europe. Why and for whom?

Recently Dazed and Confused magazine published anonline video that dealt with colorism and how Black girls were particularly affected by it. Despite the relevance of the topic, it came across as odd given that there was no precedent in the magazine for it. Were they simply jumping on the bandwagon of #woke? In the comment section plenty of Black girls were curious as to why Dazed had made the video. Their questions kept extending the thread. But this, like other pertinent questions on European curators’ curatorial decisions, remain unanswered.

By Will Furtado.

from

In Conversation

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

‘To Treat Process with Care and Intention’: Favour Ritaro Carries Forward Important Curatorial Legacies

from

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

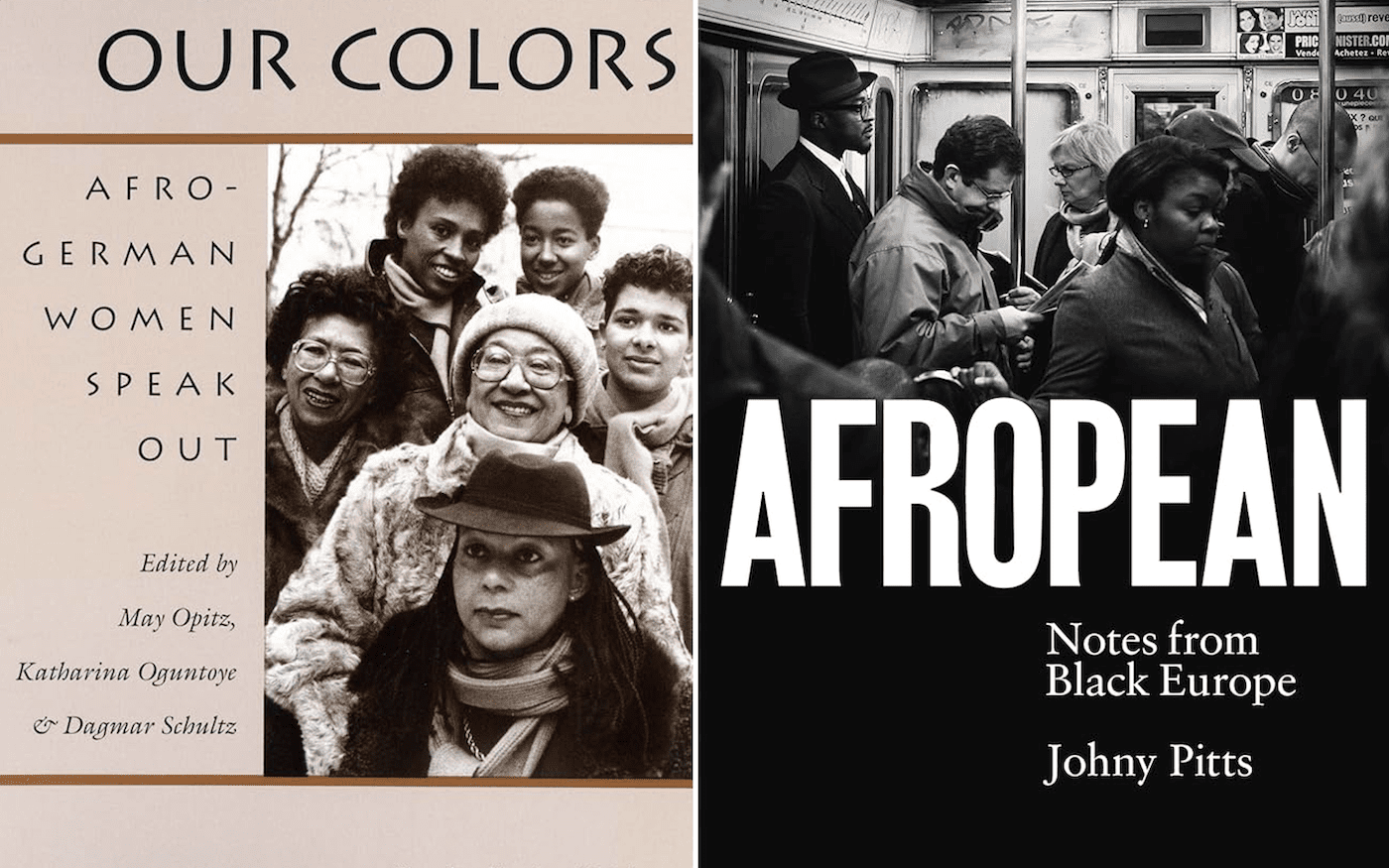

Thinkers and Titles: On Black German Literary Tradition